In the wake of Hurricane Maria, opinions are divided over the extent to which banks in Puerto Rico may cut back on their operations, and if any of them might leave the island altogether. The September 20 storm, which featured sustained 250 kilometre-an-hour winds, knocked out the country’s entire electricity grid, devastated mobile phone towers and other vital infrastructure and left thousands of citizens with flooded and/or roofless homes.

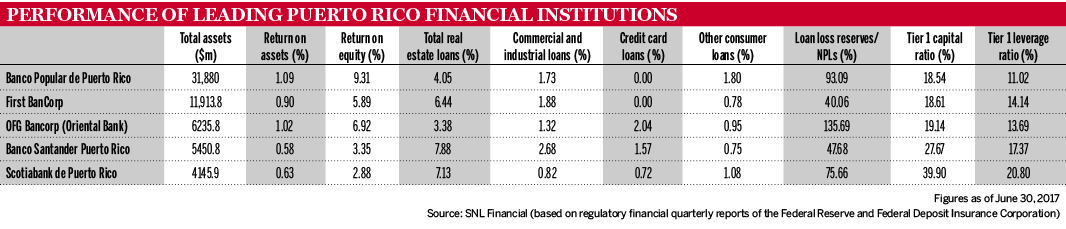

The main banks on the island – all US owned and significantly focused on retail banking – are Banco Popular de Puerto Rico, with about a 50% share of the system’s total assets and easily the largest branch network, and FirstBank Puerto Rico and Oriental Bank, which together have about a 30% asset share. By contrast, the other players – which are smaller and mainly oriented towards commercial banking – are Spain’s Banco Santander Puerto Rico and Canada’s Scotiabank de Puerto Rico, with a combined 20% asset market share.

Most of these banks’ main offices are in Hato Rey, the financial district of the capital, San Juan. Here streets turned into muddy rivers, trees snapped and windows shattered, but the concrete buildings survived and had diesel-powered back-up electricity generators, according to bankers.

Exodus averted?

George Joyner, commissioner of the Office of Financial Institutions, the Costa Rican banking regulator, believes none of the five banks will leave the island. However, he says: “I do see them increasing their geographical asset diversification while waiting for the Puerto Rican economy and demand to pick up. Initially there might be some shrinkage.”

Geographical diversification is not necessarily a positive, however. Banco Popular, FirstBank and Scotiabank were also affected by hurricanes in September that tore through other Caribbean islands where the lenders have assets – the US Virgin Islands in the case of the first two banks, while Scotiabank, the oldest non-US bank in Puerto Rico, is a regional leader in the Caribbean as a whole, so it was even more broadly impacted.

However, Scotiabank, Santander and Banco Popular also have significant operations on the US mainland, outside the range of the storms. Santander has a 100% ownership of Sovereign Bancorp, which operates in the north-east of the US, while Popular has a bank in New York.

Barry Bosworth, an economist and senior fellow at the Brookings Institute, has a different view from Mr Joyner. He believes some banks in Puerto Rico will gradually cut back and then leave, saying: “This is a big hit for people with an interest in financing economic activity on the island. If you look at the financial indices you’ll see that the value of Puerto Rico public debt has plummeted unbelievably. The same thing has happened to private debt. So people [bankers] must be asking, what’s the prospect of us getting this mortgage repaid? What’s the prospect of getting this loan repaid?

“There’s no difference between the public sector and the individual at a local level. They are both not going to be able to pay,” he adds.

A situation exacerbated

And it is not as if Puerto Rico was in a good situation before the storm. Indeed, many people – including analysts, economists and think-tank experts – believe the storm could aggravate the already considerable challenges regarding the country’s economic viability.

Consider what happened in 2016 when, by an act of the US Congress, a bipartisan Financial Oversight Management Board was appointed for Puerto Rico to supervise the island’s finances and start bankruptcy proceedings. This came after the commonwealth government sought protection from creditors after announcing in May that it could no longer meet repayments on its $72bn of bond debts – the biggest ever debt of any municipality in the US.

And that followed a decade of economic decline, excessive borrowing and a sharp exodus of residents to the US mainland, shrinking the US territory’s tax base further. All told, according to the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at City University of New York’s Hunter College, almost 500,000 people had left the island since 2008 – a drop of 11%. Moreover, the centre estimates a further 470,335 residents (or roughly the total amount of people who emigrated in the past decade) will now leave – but in the course of just two years, from 2017 to 2019.

A trend of professionals, such as doctors, and working age adults departing to seek employment and better paid jobs and services on the mainland will also intensify, the centre says. Meanwhile, the US census estimates that 46% of residents live in poverty; and at 10.5%, the unemployment rate is two-and-a-half times the US average.

Puerto Rico’s litany of woes does not end there. According to most commentators, the relief effort in the first two months after the storm has been chaotic. Ignacio Alvarez, chief executive of Banco Popular de Puerto Rico, says: “We all probably felt that the aid was a little bit slow in getting here in the beginning. Maybe not everyone realised the severity of the devastation.”

Power outage

Puerto Rican banks have been deeply affected by the hurricane damage. “Our biggest challenge is how to operate in an economy that is off the electric grid. Most of our businesses today are being powered by diesel generators,” says Mr Alvarez. Two months after the storm, most of the island was still without electricity and connections to wireless internet. Only one-quarter of points of sale in shops, businesses and supermarkets were functioning, according to Mr Joyner.

Mr Alvarez adds: “Telecommunications remain spotty. The business in credit and debit cards is way below normal in many businesses because of the lack of data transmission. Banks have not been able to accept credit and debit cards.”

Small wonder in such circumstances that Puerto Rico’s five largest banks (though the details of their programmes vary) all declared a moratorium to the end of December for employees and customers on the payment of credit card and personal loans, auto loans and mortgage payments. Simultaneously, Banco Popular and Banco Santander’s subsidiary have been contacting businesses that play a critical role in the country’s recovery, to work out if they will need new loans, say Mr Alvarez and Fredy Molfino, CEO and president of Banco Santander Puerto Rico.

One consolation following the catastrophe is that the construction industry, in the doldrums since 2006, when Puerto Rico began experiencing its housing market bust, is rebounding. As it is a big employer, this has a positive multiplier effect. “Companies such as hardware stores just can’t get enough plywood to sell. Businesses that sell generators will probably sell the same amount of generators they normally sell in five years, in six months,” says Mr Alvarez.

Conversely, the tourist industry, which is worth about 10% of Puerto Rico’s gross national product (GNP, which was $70bn in 2016, according to Moody’s) and competes with similar destinations in the rest of the Caribbean, is set to lose an entire season. After seeing television footage of flattened vegetation and destruction, few tourists are likely to want to visit in the next six months.

Creditors’ reaction

Another development with repercussions for the economy and banks in Costa Rica is that some large creditors – hedge funds and mutual funds – that had held on to their share of Puerto Rico’s estimated $72bn bonds even after it went into bankruptcy proceedings in 2016 have basically recognised that it would be impossible for these debts to be repaid and gave up trying to get their money back. According to the Wall Street Journal, in October several of these funds sold more than $8bn of Puerto Rico bonds at about 30 cents to the dollar.

Not all creditors are prepared to throw in the towel, however. James Spiotto, managing director at Chicago-based Chapman Strategic Advisers, which advises on municipal restructurings, believes creditors should wait for Puerto Rico to overcome its humanitarian crisis and build back its economy, and then talk about how much can be repaid. “That’s the way it’s going to go. But that doesn’t mean you are going to wipe it clean,” he says.

But while Mr Bosworth at the Brookings Institute believes there may be some insurance pay-offs for bonds that are insured, he says: “That is basically one big battle that will go away, freeing Puerto Rico to focus on the future of its own economy.”

Meanwhile, the Financial Oversight Management Board is assessing the costs of the hurricane damage and revising its fiscal stabilisation and fiscal management reform plan for Puerto Rico. It has asked the commonwealth government and the island’s heavily indebted public corporations, including the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (Prepa), the Aqueduct and Sewer Authority, the Highways and Transportation Authority and the University of Puerto Rico, to submit their fiscal proposals, with a view to reaching certification of a new plan by February 2, 2018.

Preliminary estimates by Moody Analytics put Puerto Rico’s hurricane losses in terms of economic output at between $20bn and $40bn, equivalent to as much as 57% of the island’s GNP. In a broader estimate by Moody Analytics that includes destruction of property, losses go as high as $95bn – all of which comes on top of Puerto Rico’s total debt of more than $120bn once pension obligations that start becoming due in 2018 are included.

“Hurricane Maria and Irma have fundamentally changed Puerto Rico’s reality and the revised fiscal plan must take that new reality into account," the Financial Oversight Management Board said in a press release after meeting at the end of October.

Hope of reform

But are there any other opportunities for banks that may arise from the disaster besides the boost to the construction industry? One development that could potentially bring merger and acquisition advisory and consulting business, and loans to banks down the road, is if there are moves by Puerto Rico and the Financial Oversight Management Board to privatise some or all of Prepa, and some of the country’s other public corporations as well.

The replacement of Prepa’s antiquated infrastructure is widely considered overdue. With imported fossil fuel generation plants concentrated in the south of the island, most of the population living in the north and power lines linking the two crossing central mountainous areas, the system is neither resilient nor rationally distributed and outages occurred frequently even before the hurricane. Furthermore, the system is a bone of contention as the costs for ratepayers are almost double electricity costs on the mainland US, which is a burden to businesses and economic growth.

But another opportunity where banks could have an important role is in channelling the infusions of US disaster aid, which includes funds (90% financed by the US government) to help Puerto Rico meet its short-term liquidity obligations, such as payroll costs and pensions, and also soft credits for residents and local businesses to pay for damage to buildings and inventory. Substantial private insurance payments to individuals and businesses may also be made primarily through banks.

Meanwhile, Mr Joyner at Puerto Rico’s financial regulator says banks have done a good job of reshaping their balance sheets and decreasing their direct exposure to the commonwealth government and publicly owned corporation debt. Notwithstanding that, as second quarter figures for 2017 show, while all five banks are well capitalised and liquid, profit ratios are comparatively lower for the non-US-owned banks and their non-performing loan rates comparatively higher (see chart).

Meanwhile, a sign of how far loan growth has declined in the past decade is that total loans, which amounted to more than $60bn in 2008, were only about half that amount (or $33.5bn) as of June 30, 2017, according to the financial regulator.

An island marooned?

The biggest imponderable, though, both for banks and the economy, is that in the absence of large-scale, long-term US government financial support (which the White House and the Republican-controlled Congress appear to have ruled out), it is difficult to see how the island’s fundamental challenges of how to make the economy grow again and how to stop outward migration by creating jobs might be reversed.

There is not much room for optimism. In the all-important manufacturing industry, pharmaceutical and software companies that have made significant investments are expected to get their plants up and running again. But the impact of the hurricane has been huge and the experience has to have been negative in terms of whether they would expand in future. “I don’t expect to see a mass exodus of economic activities but the prospects of some growth in the future has certainly diminished,” says Mr Bosworth.

Furthermore, the tax benefits that Puerto Rico offers manufacturing multinationals (independent jurisdiction or offshore tax advantages) are similar to the tax benefits offered by Ireland and Singapore, neither of which suffer from hurricanes.

Over the years, proposals to make Puerto Rico an international financial centre, an international business services centre and a regional maritime hub have been considered to stimulate growth. “These were good ideas but Miami thought so too. And Miami has jumped in over the past decade and I don’t think Puerto Rico can catch back up,” says one independent economist. In short, it is hard to come up with an economic programme for Puerto Rico’s future that is based on growth where the country has a comparative advantage.