Cautious is perhaps the best word to describe China’s banks in 2017. The country’s economic slowdown is putting pressure on asset quality, net interest margins have dropped and financial regulators, particularly the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC), are cracking down on malpractice in the financial sector.

Against this backdrop, China’s larger banks are focusing on diversifying income sources cautiously through retail banking, fee-based business and international expansion. As a testament to this theme of prudence, even Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), the top bank in the world by Tier 1 capital according to The Banker’s Top 1000 ranking, is renewing its focus on its home network.

With their enormous deposit bases, strong government support and capillary presence across the country, China’s largest banks are best placed to tread through a tricky market. Some, such as Shanghai Rural Commercial Bank (SRCB), are even preparing an initial public offering (IPO). However, smaller lenders, with limited deposit bases and weaker profitability, might find it harder to make it through China’s transition from an investment-led to a consumption-led economic model, according to market participants.

Sovereign downgrade

China’s economy is going through a delicate transition. So far, economic growth has largely relied on investment flows financed by bank credit. As a result, leverage levels have skyrocketed, with Chinese total debt accounting for 257% of gross domestic product (GDP) by the end of 2016, according to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

“Primarily, the issue is that there is a growing gap between [China’s] actual growth rate and the underlying potential growth rate of the economy,” says Michael Taylor, managing director and chief credit officer at Moody’s Investor Services. He believes China’s underlying potential growth rate is about 5% – 1.7 percentage points short of official 2016 numbers.

“That gap is being filled by policy stimulus, mainly fiscal. Growth is being maintained at levels that may not be sustainable in the long term,” says Mr Taylor. On May 24, Moody’s downgraded China’s sovereign credit rating one notch to A1.

Predictably, Chinese authorities were not pleased with the decision. “We tried to explain quite clearly what the reasoning behind the downgrade was. I believe the authorities understand our rationale,” says Mr Taylor.

Downgrades on the cards

The effect of the sovereign downgrade on financial institutions was limited. This is partly because Moody’s had already downgraded at least half of the Chinese banks in its portfolio in 2016, after changing the outlook for China’s sovereign rating from 'stable' to 'negative'.

Agricultural Bank of China (ABC) is the only bank that Moody’s has downgraded following May's sovereign ratings cut, to A2 from A1. ABC has competitive advantages over its peers, with more branches in rural areas and a stickier deposit franchise – and therefore more liquidity.

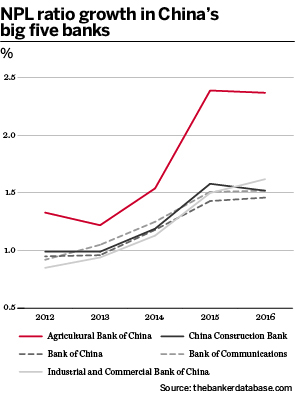

“[But] a higher non-performing loans [NPL] ratio and weaker capitalisation and profitability versus its peers means ABC’s standalone financial strength is weaker than China’s other large banks,” says Sonny Hsu, senior credit officer at Moody’s. In 2016, ABC registered the highest NPL ratio among the big five banks (Bank of China, ABC, ICBC, Bank of Communications and China Construction Bank), at 2.37%.

After the sovereign ratings cut, Moody’s also put Bank of Communications on review for a downgrade. Compared with the other big banks, Bank of Communications has weaker profitability and is more reliant on wholesale funding. This is worrying at a time when China’s regulatory crackdown has sent interbank market rates soaring. Bank of Communications also has a higher loan-to-deposit ratio than its four peers, indicating a weaker liquidity profile. Moody's will review these aspects of the bank in the next three months.

Out of China’s top five banks, Bank of Communications is notable for having the largest exposure to wealth management products – instruments sold to Chinese retail investors that offer higher yields versus bank deposits and are backed by bonds, interbank placements, bank loans and trust loans. Until 2017, these products were not included in banks’ balance sheets, making them harder to monitor.

NPL problems

It is fair to point out, however, that ABC and Bank of Communications are not the only banks facing challenges in China. Even the other big five banks have seen their NPL and loan loss provision ratios creep up. Bank of China registered the highest jump in loss provisions to total gross loans, a threefold increase to 0.9% in the three years to 2016.

At ICBC, chairman Yi Huiman says that although the bank’s NPL ratio rose to 1.62% in 2016, the bank's asset quality started bottoming out in the last quarter of the year. “This is shown in our NPL ratio slowing down and provisioning ratio improving,” he says. ICBC has also revised its credit structure to prioritise prudence. “On the one hand, the total size of lending is prudently increasing, and at the same time we have increased the proportion of individual loans and lending to [the economy’s] key sectors,” adds Mr Yi.

Beyond the big five, other lenders such as Postal Savings Bank of China (PSBC), which boasts one of the largest branch networks in the country, are also mindful of NPLs. “We stick to a prudent risk management philosophy. By the end of the first quarter in 2017, our NPL ratio was 0.85%, only half of the industry average in China,” says PSBC president Lyu Jiajin.

Mr Lyu attributes this strong performance to PSBC’s “special” asset structure. “On one end, we extend loans to large enterprises and strategic industries with low risks, on the other end we provide loans to retail customers and small and medium-sized enterprises. There is some turbulence but NPLs are under control,” he says. Accord to Mr Lyu, PSBC’s retail banking and rural services were key areas of interest for investors involved in the bank’s jumbo $7.4bn Hong Kong IPO.

SRCB's IPO

SRCB is another bank widely deemed to have performed well. The bank’s NPL ratio dropped from 1.38% in 2015 to 1.29% in 2016. “In the next 12 months our asset quality will be the most important thing for us since we want to [issue an] IPO. We have to meet certain standards. We will be increasing internal control, corporate governance, compliance and asset quality,” says SRCB president Xu Li.

A 20% year-on-year growth in total assets in 2016 is driving SRCB’s IPO decision. “[This has] put pressure on our capitalisation. We meet all CBRC capital requirements now, but if we rely only on our profits, it may be difficult to [continue meeting these requirements] in the next two or three years,” says Mr Xu.

SRCB is preparing the IPO documentation and CBRC fully supports the deal, according to Mr Xu, who believes the IPO will launch in the next two or three years.

“We need to wait; there is a long list,” he says. SRCB plans to list in Shanghai, following in the footsteps of peers Shanghai Pudong Development Bank and Bank of Shanghai. Banks such as these, which are owned by the municipal government, typically list in their home markets.

Bank of Shanghai eyes H-shares

In Bank of Shanghai’s case, listing has helped it improve corporate governance and capital adequacy. “The IPO has also put more pressure on senior executives,” says Jin Yu, Bank of Shanghai's chairman. The bank listed in Shanghai in 2016 after a 10-year wait, with a Rmb10.7bn ($1.57bn) deal that was 763 times oversubscribed, according to Reuters.

The IPO will help replenish the lender’s Tier 1 capital after Bank of Shanghai’s total assets and liabilities both rose by about 30% in the three years to 2016. Bank of Shanghai is also keen to boost its capitalisation in light of the CBRC proposing higher capital adequacy requirements. “We asked our executives to do capital replenishment via preferred stocks and subordinated bonds. This has been approved by the board but not by the shareholders yet,” says Mr Jin. The lender’s BIS Tier 1 capital adequacy ratio stands at 11.13%, according to The Banker Database.

Bank of Shanghai is also considering a second IPO in Hong Kong. “It would make sense for us to list in the H-share market,” says Mr Jin. “It would help expand our horizons, it would help us get to know what overseas investors care about and it would help us improve our corporate governance.”

Given that the bank listed in Shanghai only in 2016, there still is no set time for an H-share listing, which has already been approved by Bank of Shanghai's board and shareholders. The price of many bank H-shares is relatively low at the moment so it is not a good time to list, adds Mr Jin.

Retail priority

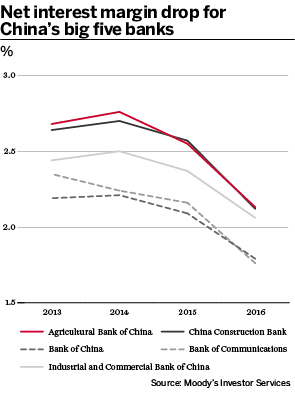

In addition to pressures on asset quality, Chinese banks are also fighting drops in the net interest margin (NIM). “The Chinese market is liberalising interest rates so the NIM dropped in 2015 and 2016. But in [the first quarter of] 2017, the NIM was very stable and is now increasing,” says PSBC’s Mr Lyu.

“For every basis point drop in the NIM, our net interest income has dropped by Rmb2bn. In 2016, the NIM dropped year on year by 21 basis points, so our net interest income fell by Rmb40bn,” says ICBC’s Mr Yi. However, net interest income accounts for a smaller proportion of total profits (54%), down from 75% a decade ago.

To offset the drop in the NIM, Chinese banks are focusing on retail banking, which has strong potential and lower risks compared with corporate banking. China’s high leverage problem is concentrated in the corporate sector, whose debt accounts for 166% of the country's GDP.

As a result, the bulk of Chinese bank credit is flowing to the household sector. By the end of March 2017, outstanding household loans had grown 24.6% year on year, according to data from the central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC).

“We have great bargaining power on the price and the risk is diversified. Business is also very stable. These are some advantages that corporate credit does not have,” Mr Lyu says of retail loans. Retail deposits take up 80% of PSBC’s total liabilities.

Lower NPL ratios for individual customers (1.22%) compared with corporate clients (1.96%) are also pushing ICBC to prioritise retail. “The quality of individual lending is very sound… individuals still have big potential in terms of bank borrowing versus government and business sectors,” says Mr Yi. At Rmb4200bn, outstanding individual lending accounts for 32% of ICBC’s total loan book.

“The retail sector will have many more opportunities in the future,” says Mr Jin at Bank of Shanghai, which in 2016 set up consumer finance company ShangCheng alongside Ctrip – one of China’s largest online travel services providers – among other investors. “We have made a strategic decision to increase personal consumption loans. As GDP and people’s wealth grows, there is big demand to increase consumption,” says Mr Jin.

Mortgage acceleration

SRCB is also keen on growing its retail franchise. “As the NIM dropped in the past two years, we focused on growing our retail business. Our personal housing mortgage loans increased by Rmb33.4bn from 2015 to 2016,” says Mr Xu. In ICBC’s case, residential mortgages grew 28.8% in the same period.

Mortgage lending in China has accelerated rapidly, backed by growing per capita disposable income and high property demand in major centres such as Beijing and Shanghai. While some analysts report that real estate projects in smaller cities are likelier to be speculative, bankers in large urban areas do not fear a real estate bubble.

“The rapid expansion of the real estate sector is not necessarily negative for the economy,” says Mr Jin, while Mr Xu adds: “In Shanghai, real estate demand is very [strong]. I don’t think there will be a collapse in prices. There are also controls that are curbing the bubble.”

Cities across China have been rolling out tougher restrictions to contain property demand while banks in large urban centres have started hiking mortgage rates for first-time home buyers. As a result, in March 2017, growth in mortgage loans slowed for the first time in 23 months. New home loans totalled Rmb361.7bn, down Rmb22.2bn from March 2016, according to PBOC data.

Chasing fees

In addition to retail banking, boosting fee-based income is another way for Chinese banks to fight low margins. In 2016, SRCB’s credit card fee income increased by a whopping 84% year on year. In the same year, the bank added 100 staff to develop private banking and asset management, and set up a private equity fund to invest in Shanghai pharmaceutical, construction and hi-tech companies.

City peer Bank of Shanghai saw its fee-based income rise 11% year on year in 2016. Meanwhile, PSBC’s fee and commission based income has grown 30% annually for the past three years.

To ICBC’s Mr Yi, incorporating asset management into retail banking and investment banking into corporate banking is essential, as almost 5% of bank residential deposits are transformed into asset or wealth management accounts every year. It is a trend that is moving from urban to rural areas, he says.

Meanwhile, China Minsheng Bank aims to expand its intermediary business, investment and transaction banking as well as asset management to boost fee-based business, according to chairman Hong Qi.

In addition to retail and fee-based business, international expansion also helps Chinese banks fight low margins at home. Thanks to an upgraded Hong Kong licence, Bank of Shanghai can now offer Chinese corporates capital account as well as current account services. “We will have more cross-border business in the future,” says Mr Jin. Even SRCB, which today has no international presence, is considering expanding overseas on the back of customer demand. The bank has yet to finalise plans.

ICBC’s home focus

In a change of strategy, ICBC is slowing the aggressive international expansion spearheaded by former chairman Jiang Jianqing over the past decade. “Our international network has already been established. In the future, we will grow further in certain regions, we will increase global integration and there will be opportunities in [China’s] Belt and Road initiative,” says current chair Mr Yi.

He stresses this does not mean ICBC is turning inwards. Indeed, at the end of March 2017, overseas assets accounted for 10% of the bank’s total assets – a target ICBC had planned to reach in 2018 or 2019. ICBC’s overseas priorities have changed to becoming a mainstream bank in the markets it has already entered.

As the pace of ICBC’s international expansion slows, the bank will focus on developing its top Chinese urban outlets, which have strong profitability and low risk. “Just one-quarter of our 320 city outlets account for 90% of ICBC’s profits. Beijing alone accounts for 13% of the bank’s profits,” says Mr Yi.

The bank will strengthen a full range of services – retail, corporate and investment banking – in the 80 most promising city outlets, among which Beijing, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Wuhan and Nanjing are particularly strong. There are another dozen smaller cities such as Changsha and Kunming that also look promising. “They may not be doing as well as the big city outlets, but we have carried out in-depth studies and we believe they will catch up,” says Mr Yi.

Even China Minsheng Bank, which is mostly privately owned, has now established a presence in every Chinese province.

PSBC’s rural e-commerce

When it comes to home focus, however, a clientele of more than 500 million puts PSBC ahead of the curve. While many commercial banks are scaling back their bricks-and-mortar operations, PSBC wants to develop its network further. “We want to improve the product marketing of our physical network and decrease costs,” says Mr Lyu.

PSBC will also focus on developing e-commerce in rural areas through its Ule.com platform, which facilitates the trade of industrial products between urban and rural regions. For this, PSBC’s access to China Post’s capillary logistics and distribution network will be a precious advantage. Having strategic investors in tech giants Ant Financial and Tencent is also helping the bank develop digital products and IT system interfacing.

Low net interest margins, China’s economic slowdown and regulatory reforms are making the country’s banking sector difficult to navigate, especially for its weaker smaller banks. However, top lenders’ cautious approach to diversifying income sources and prudent risk management is boosting their resilience at this uncertain time.