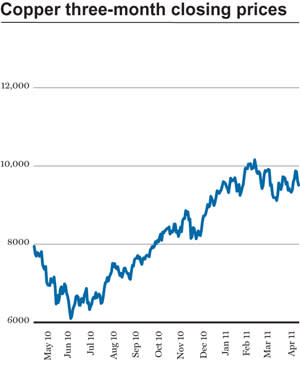

China’s strong demand for copper is seen as a prime indicator of the momentum behind its economic growth. Globally, some analysts point to rising copper prices as a sure sign of economic recovery taking root. So, when copper starts to build up in bonded warehouses in China, rather than being in the domestic market, alarm bells start ringing.

Reports of large inflows of copper after the Chinese New Year in February not passing customs but sitting in warehouses has prompted worries that China’s real demand for copper is weakening, causing a stockpile to build up, which raises questions about China’s economic growth patterns and the dynamics of the global economy.

Copper has been trading significantly lower in Shanghai than on the London Metal Exchange, reflecting a stockpile in bonded warehouses that initial reports put at 400,000 tonnes. This figure was later revised up to 600,000 tonnes by the end of March. Demand from China has certainly fallen compared with last year. Barclays Capital estimates average refined copper imports in the first quarter of 2011 were 181,000 tonnes per month, 25% lower than 2010’s monthly average.

Copper as collateral

Compounding concerns over China’s real demand were suggestions that a high proportion of imported copper was being used for financing purposes, rather than feeding domestic industrial use. One might typically see about 100,000 tonnes of copper brought on a cash basis into China each month, but traders have suggested that in March, for example, hardly any copper was imported on a cash basis. The implication is that copper’s value is as collateral for loans, or to support inventory financing deals, as tightening monetary policy in China squeezes bank lending.

"I have spoken with Chinese companies on the ground and it is hard for them to get support from the banks, which have problems with the amount of money they can lend because their reserve ratios have been raised many times to a record high level and the risks remain to the upside,” says Judy Zhu, commodity analyst at Standard Chartered Bank, who has recently returned from assessing warehouse stocks in China.

In fact, inventory financing has become so common that one Standard Chartered report suggested that copper could be rebranded as a form of collateral for loans rather than a commodity. Borrowing copper and converting it into cash can be cheaper than traditional borrowing.

It seems Chinese importers are paying the terms of letters of credit. They can buy, for example, a ton of copper at $10,000, obtain a letter of credit from a bank by paying 20%, sell the copper – either domestically or by re-exporting it – and invest in high-yield assets, such as the property market, then pay off the letter of credit when the term is up, typically after 90 or 180 days.

Inventory financing

“My sense is that the majority of stock in Shanghai’s bonded warehouses is tied up in financing deals. It makes no sense for importers to sell to China’s domestic market, so they are using that material to get loans from banks. Some companies, such as property developers, are finding it hard to get bank financing, so they could use copper. We see copper financing go up when China’s monetary policy tightens. We saw it in 2008 and we are seeing it now,” says Ms Zhu.

What is new, she adds, is the scale. The recent levels of stocks in bonded warehouses have never been seen before. The average level is about 200,000 tonnes in the previous three years. And usually material is there for less than one month, but some of it has been sitting there for more than two months now, and more inflows of copper are expected when outflows are low.

“It has affected copper prices in the past few months. The copper shipped to bonded warehouses reflects not only real copper demand, but also speculative buying. If monetary policy tightening comes to an end then bank lending will rise and many will abandon commodity financing deals,” says Ms Zhu.

Exercising caution

Some analysts are keen to calm fears about the impact of inventory financing, believing copper tied to financing deals does not account for the bulk of bonded warehouse stocks. Barclays Capital analyst Nicholas Snowdon believes it is wrong to overstress the degree of softness in the Chinese market experienced during the first quarter of 2011.

“While certainly mildly weaker than expected, we believe the increase in stocks should largely be seen as a redistribution of material along the supply chain rather than evidence of a surplus developing in the domestic market. A key comment from [copper] consumers globally is that tightness in credit has severely constrained the amount of working inventory they can afford to hold. This has resulted in inventories being redistributed to more 'efficient' locations along the supply chain. We see this in Europe, the US and especially China.” says Mr Snowdon.

Copper buyers, he adds, are destocking, holding two to three days’ material, rather than two to three weeks' worth. “In China, stocks have thus been redistributed to a more profitable place on the supply chain, the bonded warehouses, where they are off balance sheet. There, the material can potentially be financed, which is an advantage if credit is tight. If it is in a consumer’s back yard it is just depreciating,” says Mr Snowdon.

Lack of transparency

A lack of transparency means it is hard to confirm how widespread these financing deals are and who is involved, so it is difficult to assess the impact they are having on copper prices. Some are bearish, fearing that if prices reach a tipping point this may prompt a large-scale sell off. Others are concerned it may make the market tighter.

“We know that enough is tied up that when Japan bought 100,000 tonnes of cathode [made of copper] from China in the month after the earthquake it doubled physical premiums in China. This shows that some of the material is tied up in financing deals or at least not freely available to the market, although we urge caution in overstating the magnitude. Either way, ultimately the overwhelming majority of the material in the bonded warehouses will be used in China, it is just a question of where it sits in the interim,” says Mr Snowdon.

Assuming annual Chinese demand for copper is about 8 million tonnes, then 600,000 tonnes in China’s warehouses represents only about one month’s supply.

“That level is not unusual when taken within the context of how aggressively consumers have destocked at the other end of the supply chain, and an overall stocks picture cannot certainly be interpreted as overly bearish. There is no apparent distortionary impact on China’s domestic market yet. One could argue, however, that as demand picks up in the second quarter, the physical market will be tighter than otherwise would have been the case due to the financing deals,” says Mr Snowdon.

General trend

Concerns about inventory financing skewing the market are not confined to copper. Anecdotal evidence suggests inventory financing is happening across a range of commodities. In fact, it is a familiar practice in base metals.

This trend has been evident in the aluminium market for the past two years, though using a different mechanism to the one currently used in China for copper. In 2009 and 2010, a high proportion of the reported 6.5 million tonnes of aluminium inventory was tied up in long-term financing deals, making the physical market very tight despite a modest supply surplus.

“Taking aluminium loosely as an example of the potential effect of financing deals, the impact could be that if demand picks up in China we may see the domestic copper market tightening as holders of material wait for higher premiums to break their financing deals,” says Mr Snowdon.

Furthermore, China’s State Administration of Foreign Trade has recently moved to strengthen the administration of foreign exchange business, implementing rules that will curb at least some types of inventory financing activity. The tide of financing should abate in the second quarter of this year without triggering a chain reaction of unwinding existing deals.

Long-term promise

Looking ahead, some unwinding could mean a reduction in buying from international markets, and some copper from the bonded warehouses may be exported. This could have a negative impact on prices, but the downside should be limited and any bearish fears should give way to long-term fundamentals.

“In the long term, China's demand for copper and other commodities will be strong as industrialisation continues. So, there is long-term support for commodities prices, and copper has supply-side problems, with worries about supply growth over the next few years," says Ms Zhu.

The copper market should not lose sight of the bigger picture of Chinese demand, urges Mr Snowdon. “[The first quarter of 2011] saw weaker than expected copper demand in China, but a return to positive demand growth is expected the further we move into 2011. We are working on the basis of a sizeable global market deficit in 2011 of 740,000 tonnes, so the market will be very tight for the next three quarters and this has to support higher copper prices. Conditions are not as bearish as some commentators have painted them, and we firmly believe the copper bull story remains intact.”