The Indian banking industry has, over the past 12 to 18 months, witnessed a surge in digital initiatives. As banks seek to leverage technological advancements to differentiate themselves, attract customers and improve efficiency, they are launching innovative products, from mobile banking apps and social media banking to video banking and digital wallets.

Last year, in an effort to target new-age customers, India’s largest bank, State Bank of India (SBI), launched digital branches in a few cities. It was a radical move away from the bank’s traditional no-frills approach of providing banking services to the vast swathe of India’s population. Encouraged by its digital experience, SBI is now planning to extend its digital footprint to other cities and target all customers. “Digital is a key focus area for us this year,” says Arundhati Bhattacharya, SBI's chairperson.

Global consultancy firm KPMG estimates that Indian banks’ technology investment accounts for about 15% of their total spend, and this figure is expected to increase at an annual rate of 14.2%.

A tale of two halves

While on the one hand Indian lenders are leap-frogging ahead in the technology domain, they continue to face fundamental challenges that threaten to destabilise the country's banking industry. The most critical issue is that of deteriorating asset quality. The economic slowdown in the country over the past few years and policy delays led to several projects, especially in the infrastructure sector, stalling. This in turn created low corporate credit demand and burgeoning bad loans. Poor credit appraisal, disbursal and recovery mechanisms at banks also contributed to the spike in non-performing assets (NPAs).

Reserve Bank of India (RBI) data suggests that bad loans have nearly doubled in India since 2012, crossing Rs2500bn ($40bn). This is more than 4% of total bank loans. Additionally, along with restructured assets, stressed loans (gross NPA and restructured standard advances) account for more than 10% of total bank loans.

While banks have in the past resorted to a significant restructuring of loans to core sectors such as infrastructure and power, a worrying trend is that increasingly these restructured loans are slipping into the category of NPAs. Domestic rating agency Crisil estimates that as much as 40% of assets restructured between 2011 and 2014 have degenerated to NPAs.

In a country looking towards banks to fund infrastructure, the banking industry’s glut of NPAs are understandably a cause of immense concern. RBI data indicates that between 2013 and 2014, gross NPAs for India’s domestic commercial banks grew by 36%. Gross advances, in contrast, grew by only 13%.

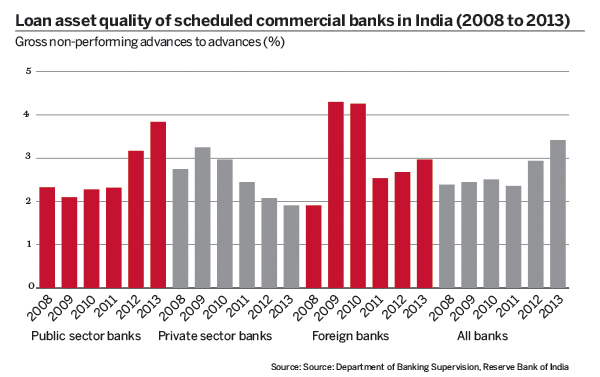

India’s NPA problem is largely centred on the country’s state-backed public sector banks. These banks constitute nearly three-quarters of the country's banking sector, but do not enjoy the autonomy that their private sector peers do, and often end up giving loans to non-profitable ventures to fulfil government diktats. Public sector banks also suffer from inadequate risk management and poor credit evaluation processes, and today account for more than 90% of the industry’s bad loans.

Moreover, corporate loans form a large share of the credit portfolio of India's public sector banks, while private sector banks have a much larger exposure to the retail sector, which has remained largely unaffected by the slowdown. Crisil estimates that the retail segment forms nearly 40% of overall advances of private sector banks, compared with 18% at public sector banks.

Over the past three years, while the weak assets at public sector banks have increased from 3% to about 5%, the number has remained at about 2% for private sector banks.

An ongoing problem

In March 2015, SBI showed a year-on-year drop in its gross NPA ratio to 4.25%, from 4.95% in March 2014. However, at India's second largest public sector bank, Punjab National Bank, the gross NPA ratio increased by almost 1 percentage point, to reach 6.55% in March 2015. Some public sector banks have gross NPA ratios at a high 8% to 10% level. At Indian Overseas Bank, for instance, the gross NPA ratio rose to 8.33% in March 2015, up from 8.12% at the same point in 2014. In contrast, among the top private sector banks only ICICI Bank had a gross NPA ratio of more than 3% in March this year. For others, such as HDFC Bank, Axis Bank and Kotak Mahindra Bank, gross NPA ratios are less than 2%.

Arun Tiwari, the chairman and managing director of state-backed Union Bank of India (UBI), says: “Asset quality issues remain a pain-point in the near term as borrowers haven’t seen any material turn around in their income flows. Though there are incremental positives, as witnessed in the reduced pace of fresh slippages, the still-high level of stressed assets on banks’ balance sheets implies a continued drag on their profitability.” UBI reported an increase in its gross NPA ratio from 4.08% to 4.96% in the past financial year. On a sequential basis, however, the bank reported an improvement in asset quality as its gross NPA ratio declined by 12 basis points from 5.08% at the end of December 2014 to 4.96% as of March 31, 2015.

RBI's governor, Raghuram Rajan, recently warned in the country's media that the bad loans situation may not yet have peaked. Crisil also predicted in a May 2015 report that India's banks would get no respite from bad loans in 2016. It predicts that bad loans will increase from 4.2% to about 4.5% of the total advances. Exposure of banks to vulnerable sectors such as power, construction and metals and mining is also expected to remain high.

Right direction

This bleak picture is in stark contrast to the exuberance exhibited by the Indian banking industry just a year back, when the new Narendra Modi-led Indian coalition government came into power. Expectations were rife that the government would implement policy initiatives that would kick-start stalled projects, especially in the infrastructure space, and that the economy would turn around in a few months.

C Jayaram, joint managing director at Kotak Mahindra Bank, says: “To be fair to the new government, the problems are fairly deep. Projects have got stuck at different stages because of a variety of issues. For example, in power projects there is absence of coal linkages, a lack of environmental clearances as well as land not being acquired. Some of the clearances are being sorted out, although land acquisition still remains an issue. But for all of this to result in projects starting to deliver will take time. And it will take even more time for new projects to kick off and the investment cycle to revive. Over the next couple of years, hopefully the climate will change.”

V Srinivasan, executive director and head of corporate banking at Axis Bank, says: “The government has initiated several policy measures and [is taking] steps in the right direction. Unfortunately, in the real economy, things take much longer to materialise.”

SBI's Ms Bhattacharya contends that the problem is that expectations of the new government were too high, but believes that things are looking up. “Although NPAs haven’t gone away, there is less stress, as there is a concrete direction to the government’s actions. We have a government that is aware of the issues and has a strong resolve to tackle these issues. However, all the issues are very convoluted and hence we have to be realistic about when they will get resolved,” she says.

She believes, however, that NPAs will not hold back banks. “This will play itself out. Workouts have to happen while we take fresh exposure,” says Ms Bhattacharya. Public sector banks, she adds, are improving their credit evaluation processes. “Earlier, infrastructure loans were given for short periods of time. Now, we are doing long-term project finance. Similarly, banks are very careful where equity comes from. Equity raising plans are considered upfront. With regards to projects that depend on land acquisition, instead of accepting in-principle approvals, we are now insisting that all land should be acquired before the bidding process. All stakeholders have learnt that there are no short cuts," says Ms Bhattacharya.

Capital conundrum

Compounding the challenge of poor asset quality is the upcoming Basel III capital adequacy guidelines, under which, as determined by the Reserve Bank of India, Indian banks will have to maintain a minimum common equity ratio of 8% and total capital ratio of 11.5% by March 2019.

While private sector banks are well placed with their capital adequacy targets, public sector banks are under immense stress. “Capital is not a problem for private sector players. Fortunately, global markets are awash with liquidity and private sector banks have a good reputation,” says Mr Jayaram of Kotak Mahindra Bank. Axis Bank’s Mr Srinivasan echoes this view. He says: “We are very well placed in terms of capital requirements, and do not have any need for capital for the next few years.”

Rana Kapoor, managing director and CEO of Yes Bank, states that all of his bank’s capital raising plans have attracted significant investor interest. The last capital raising of $500m in June 2014, through qualified institutional placement, was oversubscribed by more than five times, with a diverse investor base. Commenting on capital requirements at public sector banks, he says: “Low capitalisation levels coupled with higher stressed assets and low provision coverage in public sector banks has actually exacerbated their capital situation. Furthermore, the capital conservation buffer [CCB] requirement, kicking [in] under Basel III, will leave them in an even more challenging position.” Under Basel III, banks must have 2.5% of risk-weighted assets in the form of common equity CCB.

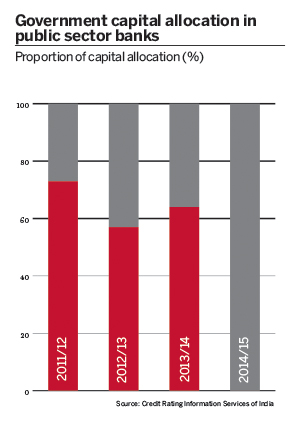

According to RBI estimates, public sector banks require equity capital of Rs2400bn by 2018, to meet capital adequacy norms. The government has already infused Rs586bn in these banks between 2011 and 2014, nearly two-thirds of which went to weaker banks. However, in the financial year 2014-15, of the Rs112bn allocated, the government disbursed only Rs69.9bn. More importantly, this capital infusion was made to only nine banks, including SBI, Bank of Baroda and Punjab National Bank, based on performance. This unexpected move led to considerable disquiet among the remaining 12 public sector banks, since capital is needed for growth and provisioning for stressed assets.

For financial year 2015-16, the government has proposed infusing only Rs79.4bn. Industry experts contend that this level of capital infusion from the government may not be sufficient to meet industry requirements, and public sector banks now need to fund growth through their own sources. “The government cannot provide the capital so the message is clear. Public sector banks need to improve governance and go to the market to raise capital,” says Shinjini Kumar, a director at PricewaterhouseCoopers in India.

Ms Bhattacharya is confident that SBI will be able to raise adequate capital in the coming years. “There are several ways of raising capital. We have a road map and we will raise capital, not by raising funds but by unlocking value,” she says.

Options abound

Accumulating capital in accordance with Basel III norms is a key concern for India's banks, according to Mr Tiwari of UBI, who says: “As this is coinciding with India’s smart take-off years, I believe the best way forward is pursuing efficiency-led growth. If efficiency gains are not there, the rate of new capital burn may remain high.”

One option for public sector banks to raise capital is to divest their government stake and bring it down to 52%, the limit set by the government. “Given the present level of government shareholding in these banks, which ranges from 58% to 89%, there is substantial ground for raising equity from the market without diluting their public sector character,” says Naresh Makhijani, an executive director at KPMG. Other options he suggests include banks exploring public and rights issues, qualified institutional placements, or issuing non-voting equity shares and differential voting equity.

Ashvin Parekh, a managing partner at Ashvin Parekh Advisory Services, says that the Indian government needs to create a framework to address public sector bank capitalisation. Without a proper framework, he says, banks will not be able to achieve the desired results, be it a dilution of government holdings or raising capital from the market.

Crisil points out that generation of capital will not be easy for public sector banks given their muted profitability and difficulty in diluting government stakes because of poor valuations. Additionally, the rating agency says that investor appetite for non-equity Tier I instruments is yet to be fully tested. Consequently, Crisil expects India's public sector banks to grow at half the pace of private banks for the next four years.

New players

The rapid growth of India's private sector banks could lead to a structural shift in the country's banking sector where the market share of new private banks, which were formed post-1990, will significantly increase. Mr Kapoor of Yes Bank says: “Over a period of 20 years, new private sector banks have increased their market share from nil to 15%, driven largely by higher capitalisation levels, better access to capital, healthier asset quality, superior human capital and advanced technology. This gain will be more pronounced going forward as public sector banks are constrained by capital.”

As such, over the coming months and years, the Indian banking sector will witness new types of players entering the field. In a move aimed at deepening financial inclusion, RBI has issued norms for payment banks and small finance banks that would allow mobile firms and supermarket chains, among others, to enter the banking arena to cater to individuals and small businesses. There is a clear distinction between these new entities and the existing commercial banks. Payment banks will be allowed payment and remittance services through various channels but will not be allowed to undertake lending activities or issue credit cards. Small finance banks will primarily undertake basic banking activities, including accepting deposits and lending to the unserved and under-served sections, such as small business units and marginal farmers.

RBI has received 72 applications for small finance banks, which include microfinance companies such as Janalakshmi Financial Services and SKS Microfinance. The 41 applicants for payment banks include big corporate houses such as telecommunications major Bharati Airtel and energy, petrochemicals and retail major Reliance Industries Limited (RIL), which is planning to roll out a 4G telecommunications service in by the end of the year.

“We understand that based on the performance of payments banks over a few years, they could be allowed to become fully fledged banks, and this could explain the interest in these licences, although RBI has not said anything about this,” says Mr Makhijani of KPMG.

Reason to be worried?

The target segment for payment banks is expected to be different from commercial banks. Typically, their target customers will be the likes of migrant labourers who traditionally do not access the formal banking network. Hence, rather than viewing payment banks as competitors, banks are looking to collaborate with them. SBI and Kotak Mahindra Bank have tied up with RIL and Bharati Airtel, respectively, for their payments bank initiative.

“It is unlikely that payments banks will cannibalise conventional banks’ business. They are creating a new banking model that will be unique to the Indian market,” says Mr Jayaram of Kotak Mahindra Bank. While it is too early to comment on the shape payments banks will take, Mr Jayaram says that companies likely to succeed in this space are those that have strong and deep distribution networks. “Clearly telcos have the strongest and deepest distribution network today and Airtel is the leader in the market,” says Mr Jayaram. The Airtel-Kotakpayment bank initiative is being front-ended by Airtel while with a 19.9% investment, Kotak is a financial investor at this point in time.

Ms Bhattacharya says: “Payments banks is a new kind of banking. The transaction value will be very small. We need to see how it pans out.” Commenting on SBI’s tie up with RIL, she says: “The relationship will be ours while spectrum usage will be Reliance’s. Reliance has a spectrum in 22 circles that will provide pan-India coverage. It will be a very balanced relationship.”

Mr Tiwari of Union Bank of India, however, warns that potential competition between commercial and payments banks should not be dismissed. “Universal banks rooted in conventional brick-and-mortar delivery channels need to have an eye on payments banks. When every aspect of banking can be done online, competitive reach is no longer determined by branch networks alone," he says.

"New bank licences will indeed usher in more competition. However, given the extent of banking penetration in India presently [the bank credit to gross domestic product ratio stands at 55%], there is enough space to grow for the existing as well as the new players without making it a zero-sum game for the incumbent.”