The collapse of Lehman Brothers and the subsequent global financial crisis is not what springs to mind when Sri Lankan bankers are questioned about the recent history of their industry. Instead, the defining moment in their recent history was the end of the country’s civil war in 2009, and the subsequent opportunities that the peace has brought.

“The entire country is now open for business,” says Ravi Dias, managing director and CEO of Commercial Bank of Ceylon. “Sri Lanka beckons to the rest of the world as a country with tremendous investment potential.”

Rajendra Theagarajah, the former managing director and CEO of Hatton National Bank (HNB), who is due to take over as the CEO of National Development Bank (NDB) in August, says: “Each week there is a new type of investor [in Sri Lanka].” He adds that the country is now seen as a frontier market in its own right – comparable to countries such as Vietnam or Cambodia – rather than an emerging market that is defined by its proximity to India.

Peace dividend

Stability took hold in Sri Lanka after the elections in 2010, according to Mr Theagarajah. Since then, the country has enjoyed a peace dividend, with a gross domestic product growth rate of 8% in 2010, 8.2% in 2011 and a slower but still impressive 6.4% in 2012.

With the development of the economy, Sri Lanka’s living standards are also going up, says D M Gunasekara, general manager and CEO of Bank of Ceylon. “Sri Lanka’s economic prospects are good and we hope to maintain a growth rate of more than 6% over the next couple of years,” he says. Rating agency Moody’s estimates that Sri Lanka's growth will be 6.5% in 2013, and 6.7% in 2014.

As part of its vision for development, which was outlined in 2010, Sri Lanka's government is aiming to almost double the rate of per capita income to more than $4000 by 2016. The national development policy also has broader goals of promoting investment in the country’s infrastructure. Ports, airports and roads are key areas of investment as are electricity, telecommunications, IT, education and health services.

HNB is one of the banks that has consciously aligned its strategy to the national plan. “The banking industry needs to rally around this development programme,” says Jonathan Alles, HNB’s new managing director and CEO.

According to Commercial Bank of Ceylon's Mr Dias, the country's position, between the shipping routes of the East and the West, make the development of its ports of particular importance to maximising its strategic location. However, he warns that improving Sri Lanka’s infrastructure will be no easy task. “The country has had to undertake accelerated infrastructure development projects to catch up for the time lost due to the debilitating internal armed conflict that it underwent for three decades," he says. "Sri Lanka’s relatively low domestic savings rate of 17% [of GDP] in 2012 has made this challenge even more daunting.” Despite this, Mr Dias believes that Sri Lanka has made encouraging progress.

A heavy burden

Sri Lanka’s economy is facing a number of other challenges. Moody’s notes that the country’s weaknesses include external payments position vulnerability, a large government debt burden and shallow domestic capital markets. A March 2013 report by ratings agency Standard & Poor's further emphasised these points.

“A narrow tax base, the debt burden from a long civil conflict and the reconstruction, extensive subsidies, and a bloated public sector have contributed to a fiscal deficit of 8% of GDP on average over the past decade," the S&P report said.

"The increase in government debt often exceeded the deficit because of currency depreciation. We estimate the general government deficit at about 6.5% of GDP in 2012 because of expenditure restraint. However, we estimate the net general government debt burden rose to just more than 80% of GDP at the end of 2012, despite an estimated 13.5% growth in nominal GDP. The increase is mainly because of the deprecation of the Sri Lankan rupee against the US dollar in 2012, as about a half of the government debt is denominated in foreign currency. The interest on government debt amounts to 40% of revenues, which is one of the highest interest burdens among rated sovereigns.”

The mood is optimistic among the country’s senior bankers, however. “We remain quite positive,” says Nihal Fonseka, chief executive of DFCC Bank. “Growth has slowed down but I think we are on a good growth trajectory. The government has to got to grips with some of the issues, such as getting the fiscal deficit narrowed and trade balances improved, but it is on the right track.” Mr Theagarajah echoes this sentiment, saying that peace has "brought a completely different perspective" to the country.

Feeling the squeeze

As well as these domestic issues, Sri Lanka has also been subject to the worldwide increase in regulation since the global financial crisis. Mr Dias says that one of the challenges for the industry is “maintaining asset quality and prudent capital levels in the face of business expansion”. At the same time, Sri Lanka’s banking industry needs to keep up with the international requirements of Basel II, implement Basel III and also comply with the International Financial Reporting Standards.

Mr Dias says that there are now additional requirements for risk management, anti-money laundering and corporate governance, which require banks to invest in new IT systems. This is proving challenging for the industry and because of this, says Bank of Ceylon's Mr Gunasekara, the industry is facing severe capital issues.

The need for capital has also been identified by Renuka Fernando, CEO of Nations Trust Bank (NTB). She says that “capitalisation is key” for financial institutions to comply with the new regulations and also support the growth in the country’s economy. “Before there were fat margins – that is no longer a reality," she says. "They are [being] squeezed because the regulator is applying pressure and because of demand and supply in the market. The cost of compliance is a struggle for some banks. To survive, smaller banks need volume and muscle to take up these costs. They have to be extremely efficient in their use of technology.

"There will probably be consolidation in the market. Banks need to become very large in size if they are able to support the growth trajectory the government has set out."

Prime numbers

According to 2012 figures from the country's central bank, there are 24 licensed commercial banks, nine specialised banks and 47 finance companies in Sri Lanka. This is a relatively large number given that one executive estimates that 50% of the country's population of 20 million is unbanked.

It also means that there are many pockets of capital in the system, says Mr Theagarajah. “We need to clean up pockets of arbitrage in the system,” he says. He believes that the ideal number of banks in Sri Lanka would be six or seven, and adds that it would be better if there were one or two big private sector banks that would be large enough to compete at a regional level.

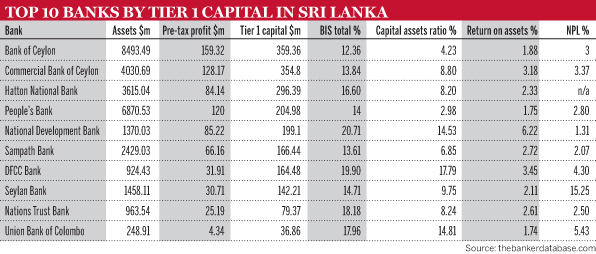

Currently, the market is dominated by the state-owned People’s Bank and Bank of Ceylon, with Fitch Ratings estimating that more than half of the sector’s assets are in the public sector. With so many banks competing for business, margins are becoming thinner. “Competition in the industry is putting pressure on margins,” says Mr Gunasekara.

Opportunities knock

Despite the competition, there are opportunities for Sri Lanka's banks to grow. HNB's Mr Alles says that as more infrastructure projects come on board there will be more opportunities for banks to participate. Aside from the opportunities in financing infrastructure projects, state-owned Bank of Ceylon has plans to focus on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and on the development of microfinance for those at the bottom of the pyramid.

One advantage for Bank of Ceylon, says Mr Gunasekara, is that the bank already has a wide network that extends across the country. He adds that the bank’s plans in the near future are to expand its network, both nationally and internationally. Bank of Ceylon already has branches in Malé in the Maldives, Chennai in India and a subsidiary in London.

After the state-owned banks, HNB is one the most established banks in Sri Lanka. Mr Alles says that one of HNB’s objectives has been to expand to all parts of the country, which has been made possible since the end of the war. “Our strategy is to generate returns from this expansion,” says Mr Alles. The bank is also shifting its attention to mobile and online banking channels in order to increase its reach, and it is focusing on improving its processes and systems to bring its cost-to-income ratio down.

At Commercial Bank of Ceylon, Mr Dias says that reducing the cost-to-income ratio has been important. Like many banks in Sri Lanka, Commercial Bank has been focusing on the SME sector and, in 2012, it raised a long-term loan of $65m from the International Finance Corporation (IFC) to mainly provide financial assistance to the SME sector. In February 2013, the bank and the IFC signed a $75m, 10-year subordinated debt agreement to further expand the bank’s operations and increase financing to SMEs.

NDB's Mr Theagarajah says that the opportunities for banks to finance the largest companies in Sri Lanka will diminish as these companies turn to capital markets. As the country develops into a middle-income country, he sees the opportunities coming from a different sector. “As the lifestyle levels go up, I see a greater role for retail banking,” he says.

New kid on the block

Commercial Bank and HNB have been in existence for 90 years and 120 years, respectively. Compared to this, Ms Fernando describes NTB, which was established in 1999, as a “new kid on the block”, something that she believes puts it in a good position. As a small bank, NTB can be nimble in introducing the changes that are necessary to be more efficient, given the capital pressures and thinning margins in the industry.

Now is the right time, she says, for the bank to create efficiencies before it starts to increase its volumes. With a history in corporate banking and a more recent focus on consumer banking, Ms Fernando aims to marry the bank’s capabilities to target the SME segment. When asked if the bank is aiming to challenge the larger, more established banks in Sri Lanka, Ms Fernando says: “We want to be among the top six in the next five years, commencing this year.”

Another fast-growing second-tier bank is DFCC Bank. Mr Fonseka describes DFCC as a unique entity, as it operates a centralised model but under two licences. Initially founded as a development bank, the bank focuses on SME and corporate project finance.

Mr Fonseka adds that one of the challenges for DFCC Bank in funding projects is getting long-term funding at a reasonable cost. “Because of the interest rate fluctuation, we see the ability to raise long-term funding as quite limited,” he says, explaining that, in the past, the bank depended on multilateral institutions such as the World Bank. “Now we are looking to diversify and to tap the international capital markets," he says.

In June 2013, news agency Reuters quoted the deputy treasury as saying that NDB and DFCC are each planning a $250m, 10-year bond issue. At DFCC's retail bank, DFCC Vardhana Bank, Mr Fonseka says that much attention is being paid to building up the personal financial services and investing in delivery channels in order for the bank to expand across Sri Lanka.

Such opportunities have been made possible since the ending of the civil war. Although there are numerous challenges for the banking sector, including capital constraints and intensifying competition among many players, senior bankers are optimistic about the growth prospects of Sri Lanka’s economy and its banks.