Sandwiched between Afghanistan, China, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, the remote landlocked central Asian country, will celebrate 20 years of independence this month (September 2011). Having survived the financial crisis without a single default, its banks have something to celebrate too.

Editor's choice

Tajikistan is one of the poorest of the central Asian countries, with a gross domestic product (GDP) per capital of about $800. Almost half of its male population of working age have taken the plane to Russia and Kazakhstan in search of work and send money back home. Remittances form the bedrock of Tajikistan’s economy, accounting for the lion’s share of its GDP.

Struggling with the challenges of a Soviet legacy and an impoverished population, Tajikistan’s banks have their work cut out. But with help from the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the World Bank and its private sector lending arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the country’s banking sector is growing fast and moving into new areas of business. It weathered the financial crisis and came out the other side in better shape.

“Commercial banks are now adequately capitalised. Moreover, when you look at selected banking indicators such as deposit growth and loan growth, they are all improving,” says Sharif Rahimzoda, chairman of the National Bank of Tajikistan (NBT), the country’s central bank. Annual deposit growth is 15% to 20% which reflects growing confidence in the banking system, he says.

Although the Tajik banking sector remained fairly insulated from the worst of the financial crisis, the downturn hit the real economy. Sharp falls in remittances from Russia and shrinking cross-border trade caused heavy currency fluctuations. This in turn prompted a deterioration in the balance sheets of the country’s banks. Non-performing loans (NPLs) across the banking sector spiked to 28% of the loan book in 2009, before dropping to about 17% today.

Closer scrutiny

The NBT's response was to step up monitoring, appointing a working group to keep a close eye on banks’ troubled balance sheets and inject liquidity into the interbank market to prevent short-term capital shortfalls. The central bank created a hotline for commercial banks’ top management, allowing senior bankers to keep the NBT informed of the latest developments so that it knew when it should take action.

NBT now operates a five-point loan classification system, with loans marked as a problem from the moment of the first late payment and moved down the rankings until they are seen as non-recoverable. “As a result of the financial crisis, we created a much more flexible and easily understandable regulatory regime,” says Mr Rahimzoda.

With this basic regulatory framework in place, the NBT can think more broadly about the development of the banking system. “Now we are in a transition period from quantitative to qualitative features such as the broadening of banking presence in rural districts, bringing more trained bank staff to rural areas and using international experts to improve skills at credit institutions,” adds Mr Rahimzoda.

Access to finance

Another key challenge that lies ahead for Tajikistan is increasing the financial literacy of the country's population and increasing the access to financial services. At present, only 2.7 million of Tajikistan’s 8 million population (less than half of the working age population) have a bank account. That is up from 600,000 in 2005 but it is still a long way from the more developed markets in the Commonwealth of Independent States. Furthermore, the NBT sees plenty of work to do in improving access to credit and debit cards, and upgrading payment systems.

However, there is enormous potential for growth in Tajikistan. One glance at the country's capital city, Dushanbe, reveals new construction sites appearing at an impressive rate, with new buildings, new roads and new power lines being built or laid by the day. This work is typically carried out by Tajik, Russian and Chinese companies.

One bank that sees the construction industry as a key growth sector over the next five years is Orien Bank, a privately held bank that was known as the Industrial and Construction Bank of Tajikistan in Soviet times. It now has 32 domestic branches, 103 sub-branch service centres and 1250 staff.

“We believe there will be huge potential in construction in the next five years. There is enormous demand for commercial buildings and apartments. We have a lot of migrants in Russia who want to use their money to buy new homes,” says Rajabbek Sulaymanbekov, deputy chairman of the board at Orien.

The bank has a global network of representative offices to help clients overseas. It partners with Citibank for US dollar transactions and Commerzbank for euro transactions. NPLs at the bank peaked at 25% in 2009, before falling to 7.8% this year.

Credit bureau needed

About 60% of Orien’s loan book is to large corporate clients. The other 40% goes to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), an area in which the bank acknowledges that credit checks are a challenge.

“We do not have a credit bureau in Tajikistan so there is no database for a client’s credit history. If a client has a bad history at another bank, we do not know about it,” says Mr Sulaymanbekov.

The EBRD is co-operating on an IFC-led project to bring international management consultants to Tajikistan to set up a credit bureau. But Nick Tesseyman, managing director at the EBRD's financial institutions division, cautions against expecting overnight changes. He points to Russia, where it took time to build up a credit database and where even after 10 years credit checks are imperfect. "It will not be a game-changer in the short-term," he says.

The banks are already sharing data on blacklisted borrowers, according to the EBRD's microfinance operations leader Firouza Iskhakova, and the IFC-backed project should begin later this year.

Orien also finds that the financial literacy of its customers is a challenge. The bank’s loan officers often find that they have to help small business clients write a business plan. Many want to borrow in US dollars to fund purchases of imports, but their sales are in local currency. Such loans would expose them to currency risk, which they may not know how to manage.

Small loans, big growth

Despite the challenges in the SME sector, by the end of this year Orien bank expects that 20% of its loan book will be at the microfinance end of the spectrum. And it is by no means the only bank hoping to take a slice of the microfinance market.

Microfinance is one of the fastest-growing forms of banking in Tajikistan. According to Shukhrat Abdullaev of the Association of Microfinance Organisations of Tajikistan (AMFOT), the sector is growing faster than in any other country in central Asia.

Most of the country’s microfinance lending organisations began life as charities working for international non-governmental organisations. But legislation passed in 2004 in Tajikistan required all charities to convert their status into central bank-regulated microfinance businesses. It was a successful change and the sector has boomed: in 2004 there were no regulated microfinance businesses, today there are 123.

“Each microfinance organisation is offering training, consultation and advice to their clients as well as loans so the sector plays a very important role in making the Tajik population more financially literate and offering finance to the poorest section of the population,” says Mr Rahimzoda

The sector has a gross loan portfolio of $333m, with the lion’s share of loans coming from three banks which operate in the microfinance sector: AgroInvest Bank, First MicroCredit Bank and Access Bank. Loans themselves can range from as little as $100 up to $50,000, with the bottom end enabling housewives to raise the money to buy a few extra chickens, a dairy cow or a sewing machine, and the top end giving liquidity to more sophisticated import-export businesses.

Interest rates on loans are high, ranging from 30% to 48%, but the returns are less sizable than they look at first glance. Most banks are using the lucrative microfinance loans in urban centres such as Dushanbe and the northern city of Khojand to subsidise the enormous cost of setting up lending service centres in remote rural areas with poor roads and a flickering power supply.

“Once you get into rural areas, operating costs rise with every extra kilometre and urban loans are used to cover the costs of reaching far-flung clients, because most microfinance businesses have a social remit as well,” says Mr Abdullaev. He adds that a headline inflation rate of 14.4% also acts as a brake on profits.

“When you take into account currency fluctuations in an economy that gets almost half its GDP from overseas remittances, inflation may be more like 22%,” he says.

Outer reaches

The microfinance sector is currently in a state of consolidation after seven years of rip-roaring growth. According to AMFOT's predictions for the next few years, weaker players may fail or be swallowed up by bigger operators, which will then have to compete for customers by expanding their product ranges and lowering interest rates.

Brampton Mundy, CEO of the First MicroFinance Bank (FMFB), which is banked by global aid organisation the Aga Khan Development Network, heads one of the biggest players in the market. The bank operates a branch and smaller regional banking service centres in the mountainous province of Badakhshan in the Pamir mountains along Tajikistan’s Afghan border. Badakhshan is the heartland of Tajikistan’s Ismaili population, who look to the Aga Khan as a spiritual leader. But in fact, only 20% of the FMFB’s business is in Badakhshan and the bulk of its operations are in the north and centre of the country.

“We are thought of as a Badakhshan-based bank, but it is a bit like saying that Royal Bank of Scotland is a Scottish bank: our business is much broader,” says Mr Mundy.

He adds that the bank has a strong social ethos and lifting the poorest Tajik communities out of poverty is part of its remit. “If you were looking at Tajikistan purely from a return-on-capital perspective, then you would not operate in rural areas at all, and you would begin by concentrating on the urban centres,” he says. But he emphasises that, for the bank to continue its social mission, it must also look carefully at the bottom line. “We are enabling our clients to improve their livelihoods and build sustainable businesses. To be successful, our own business has to be sustainable too, so we cannot just throw money away.”

Mr Mundy says FMFB did not fare too badly during the financial crisis as its credit controls were better than some smaller microfinance institutions, but it did learn some important lessons about currency risk.

Passing the risk

The Tajik microfinance industry is primarily funded by overseas organisations ranging from charities to European specialist microfinance funds such as Blue Orchard or Triple Jump. This means that the sector’s funding base is almost entirely in foreign currency. Microfinance institutions, and in fact the whole Tajik banking sector, have enormous difficulty in attracting deposits in the national currency, the somoni, given that half the country’s income is from remittances. The investors pass the currency risk onto the microfinance institutions, which in turn passed it along to the clients.

While import-export businesses in northern Tajikistan, near the Kyrgyz border, were well versed in managing currency risk, housewives in the Pamir mountains who had used US dollar loans to buy chickens or seeds found themselves unable to repay loans.

“To lend in dollars, you have to make sure that the client has access to dollar cashflow and knows how to manage currency risk. The poor cannot do that, so now we only lend in somoni to the agricultural sector,” says Mr Mundy. Agriculture makes up 30% of FMFB’s loan book, with 10% coming from mortgage financing and 60% from trade.

Too much debt

Humo & Partners, one of the top five microfinance organisations in Tajikistan which began life under the umbrella of the NGO Care International, also learned valuable lessons about credit risk management during the financial crisis. Its NPLs spiked to 17% of its loan book in 2009, but have since fallen to just 1%.

Mavsuda Vaisova, general director of Humo & Partners, says the microfinance sector weathered the crisis better than many of the banks because it is more independent and better managed than most of the banks. Even so, staff at Humo found themselves on a steep learning curve. “We expected problems with liquidity. Instead, we had money but no clients to lend to, because people were too scared to take out new loans,” she says.

The lack of a nationwide credit bureau also meant that microfinance institutions had no visibility on how leveraged their clients were. At the height of the crisis in 2009, when it began swapping data with other institutions, Humo found some clients had taken out small loans at four or five different institutions and were relying on remittance income to repay. When the money from migrant workers in Russia dried up, they found themselves in default.

“We now exchange information with other institutions and we will not lend to clients with loans elsewhere. If a client wants to expand their business we are happy to give them more credit but we want visibility on how leveraged they are. It was an important lesson to learn,” says Ms Vaisova.

Market leader

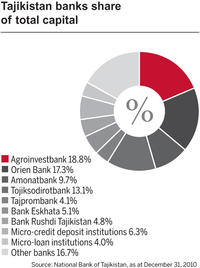

AgroInvest Bank, Tajikistan’s largest, also has a sizable microfinance business. As its name suggests, 30% of its business comes from agriculture, with 5% in mortgage lending and the rest in trade activities, with customers ranging from small retailers and importers to large state-owned corporations.

“Tajik economic development is disproportionate and that is reflected in our loan book. We would like to boost our retail banking and we are concentrating our efforts on the private sector," says AgroInvest chairman Farrukh Tagaimurodov. Because Tajikistan is landlocked and not rich in natural resources, most loans are given to finance the import of goods.

The EBRD’s decision to take a 25%-plus-one-share stake in AgroInvestbank at the height of the crisis in 2009 reflects the bank’s determination to follow international best practice in everything from assessing client credit risk to classifying NPLs. Mr Tagaimurodov says the bank has had to work hard over the past nine years to bring EBRD in as a shareholder, and has now brought international consulting firm Maxwell Stamp on board to bring the bank in line with international standards. The moves are part of a long-term plan to attract international investors and build up relationships with a network of global banks.

The bank weathered the financial crisis well, with NPLs peaking at 8.2% in 2009 and falling back to 4% today. Delays in imports had caused some clients to default, but AgroInvest Bank put an emphasis on maintaining good client relationships during the crisis, sacrificing short-term profit in order to maintain liquidity for clients and retain business.

Improving governance

All of Tajikistan's banks face challenges common to building up an embryonic banking sector in a small economy. State interference in bank lending is common, with the government often pressuring banks to lend to large state-backed projects regardless of their commercial viability.

"It would be naive to claim that there are no instances where banks are used as vehicles for directed lending by the authorities. This is an issue in many of the countries in which the EBRD operates," says the EBRD's Mr Tesseyman.

"What we are looking to foster is a gradual process of change and adjustment in the banking sector; through technical assistance, through broad engagement in the sector and dialogue with the authorities and the regulator, and sometimes by cajoling and delivering tough messages. We're seeking to ensure a more transparent and stable banking sector in the long term, even if there may be a negative short-term impact on the economy from enforcing higher standards of business conduct and corporate governance," he says.

Working with Tajikistani banks over a number of years, the EBRD aims to minimise the dangers of state interference and related-party lending, which has brought down banks in Russia, and work with the banks to improve corporate governance.

The EBRD is also working on two technical assistance projects to improve financial education in Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia. One is a scheme, which was successfully rolled out in Georgia and Azerbaijan, to persuade people to save remittances from overseas in the banking sector, which involves educating customers about banking products and how savings accounts work.

"A lot of the banks initially think that dealing with remittance receivers – including the provision of financial education to the potential customers – is costly, but in the long-run they see that the entire banking sector will benefit," says the EBRD's Ms Iskhakova.

Another EBRD plan is the introduction of a deposit insurance scheme, already carried out in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro. Mr Tesseyman says this will be "more challenging" in Tajikistan, in part because the country is less developed than the two former Yugoslavian states.

Better management

When the EBRD first began working in Tajikistan, the basics of corporate governance – from the workings of a board of directors to the split between shareholders and management – all had to be explained to senior bankers. Much progress has been made, but it remains difficult for banks to recruit and retain highly qualified staff.

After the Tajik civil war during the early 1990s, many of Tajikistan's best minds fled the country never to return. Literacy levels are still below what they were in Soviet times, and there is a shortage of secondary schools and university places.

However, there is strong potential for greater productivity and skills in the sector, despite these challenges. Tajprombank has been working closely with the EBRD to build up its SME business using software provided by the EBRD.

"SMEs are the foundation of the national economy, the main source of government revenues, and supply people with the everyday consumer items they need. Many of them have foreign investors and good quality businesses," says Tajprombank chairman Djamshed Ziyaev.

The EBRD helped train 147 specialist bank staff to deal with SMEs, enabling Tajprombank to build up its SME lending from 2% of its loan book in 2003 to 57% of business today.

Meanwhile, one of the newest players on the block, Tajikistan Development Bank (TDB), has built up a foreign exchange trading team to boost profits. Launched in 2006, the bank is the youngest in Tajikistan and has only four branches in addition to its head office. According to chief financial officer Masrur Saidov, the bank is now the third most profitable in the country despite being one of the smallest.

However, the youth of the bank is reflected in its NPLs, which currently make up 7% of its loan book, up from 3% in 2009. The bank makes 90% of its loans to companies, of which half are small businesses.

As the bank's loan book was originated at the peak of the boom and has not grown much since the crisis, NPLs have climbed as a percentage of the book, and some debtors have simply disappeared. Like Tajikistan's banking sector as a whole, TDB has good potential if it can overcome the challenges of operating in such an underdeveloped economy.