Poland’s banks are seeing a rising pile of obstacles thrown in their path by unfavourable legislation, regulation and poor peer performance, all of which are putting profitability at risk.

Their problems include changes to the country’s tax regime, plans to convert the banking sector’s large and problematic pile of foreign currency mortgages into local currency, and added costs from deposit insurance payments related to 2015’s bankruptcy of SK Bank.

Some of the pressure on balance sheets is likely to show up in 2015 results, as all banks were made to shoulder payments related to SK Bank’s bankruptcy in the fourth quarter.

Bank failure

The collapse of the bank, with assets of about 3.5bn zlotys ($860m), was the first failure of a Polish bank in 15 years. But while previous failures were largely the problem of just one institution – and of the government – today the country’s entire banking sector must pick up some of the burden through the Bank Guarantee Fund (BGF).

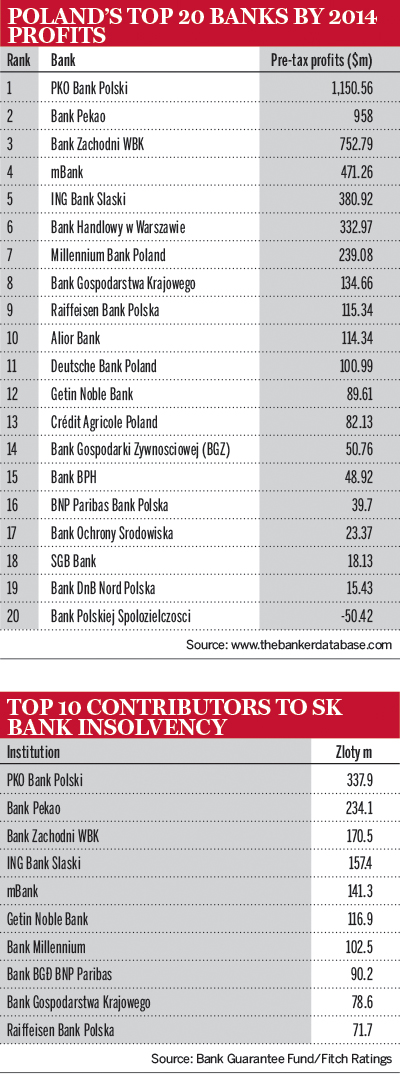

Contributions to the fund depend on each bank’s market size. The total cost to the industry from SK Bank’s failure will be more than 2bn zlotys. Fitch has warned this could trigger fourth-quarter losses at some of Poland’s less profitable banks, including Getin Noble Bank and Bank Ochrony Srodowiska.

In 2014, combined pre-tax profits for Poland’s top 20 banks were $5.07bn, of which $4.65bn was at the top 10 banks, according to figures from The Banker Database. That leaves average pre-tax profits for the other 10 at a meagre $42m.

In the nine months to September 2015, the entire sector reported $3.5bn of profits, according to Fitch, suggesting the SK Bank payments could amount to a significant hit.

In 2016, more costs are coming through the annual BGF payments, which are slightly higher in 2016 at 2.37bn zlotys for the whole sector, compared with 2.23bn zlotys in 2015. As the entirety of the costs must be recognised upfront, Fitch warned that some rated banks could report losses for the first quarter of 2016.

Taxing times

This comes as the legislative environment is raising further challenges. The country’s new conservative government of the Law and Justice party (PiS) signed into law a bank tax demanding payments of 4.4bn zlotys in 2016, which is equivalent to about 32% of banks’ annualised earnings for the first 10 months of 2015, according to rating agency Moody’s.

The tax is expected to reduce banks’ return on assets and return on equity by one-third. “Such a decline in net income would reduce banks’ ability to absorb shocks,” Moody’s warned in January. In the first 10 months of 2015, banks generated return on assets of 0.9% and return on equity of 8.5%.

But the government’s plans do not end there. It is also considering imposing a conversion of foreign currency mortgages using steps similar to those taken by Hungary’s government in 2014, which have proven costly to that country’s banking sector.

In Poland, nearly one-fifth of all loans were foreign currency housing loans to households in March 2015, according to the central bank, underlining the widespread use of the product and the potentially significant hit to banks. The impact is likely to be in a range of 30bn zlotys to 60bn zlotys, according to Fitch. That compares with aggregate Tier 1 capital of 137bn zlotys at the end of September.

Under a scheme proposed by the previous government and enacted in January, banks must contribute to a fund to provide assistance to retail mortgage borrowers struggling to meet loan repayments, irrespective of the currency they borrowed in. Initial contributions amounted to 600m zlotys, with each bank’s contribution based on its share of the pool of non-performing mortgages. Those obligations could be dwarfed if the government imposes conversion.

The PiS government is likely to take a tough stance on the banks. It aims to use the proceeds of the bank tax to finance an expansion of social spending under its revised budget for 2016. And past months have shown that the new government will take harsh measures when required.

Since it took power in October, Poland's government has been at loggerheads with the EU over changes to the structure of Poland’s highest court, and Poland’s sovereign credit rating was cut by Standard & Poor’s over what the rating agency called an “erosion of the independence, credibility and effectiveness of key institutions”. None of which will provide much encouragement to the country’s banks.

This article first appeared in the Financial Times service EM Squared.