‘‘This is the year of the bond,” enthuses Alexander Kotcherguine, the head of international business development at MDM bank. A pioneer of Russian debt instruments, the ebullient Mr Kotcherguine believes that Russia’s expanding rouble bond market is coming of age.

Investors into Russia’s young capital markets have become accustomed to stellar returns (and occasional horrific losses) since 1991 but a combination of political stability, strong economic growth and bare-knuckled competition mean that triple-digit returns are passed, says Mr Kotcherguine.

Russia’s companies are enjoying a spring after the long winter of economic chaos but are desperately short of investment capital to keep up with burgeoning demand. At the same time, the banks are awash with liquidity thanks to Russia’s raw material exports but are still cautious in lending due to a poor legal environment.

Russian companies are still not ready to turn to the stock market and raise equity finance, however, and so have gone en masse to the domestic bond markets to finance their continued expansion.

Market re-emerges

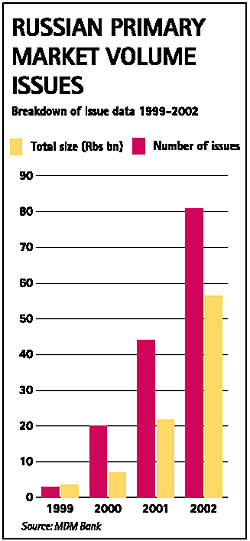

The domestic capital market, which was all but destroyed by the 1998 financial crisis, reappeared in 2001 and both the number and volume of issues have doubled every year since then. Last year, the market had its first post-crisis liquidity squeeze and several issues were either delayed or canned but, with liquidity continuing to rise and yields falling, it has shrugged off worries and by January investors were ravenous for new issues.

“By May 2003 the market was already beginning to overheat. Too many bonds had driven the yields down too low: the average was between 10%-12% but [state-owned gas giant] Gazprom was commanding 7.5%-8%. The banks and the financial markets were not ready to go this low,” says Ilya Zimin, vice-president, domestic debt capital markets at MDM.

Volume is boosted

The market had a roaring start after the new year with a fresh batch of huge bonds that will easily drive the outstanding volume of the corporate bond market this year beyond the estimated $4bn-$6bn that it was worth at the end of last year. Gazprom kick-started the activity by offering a record-breaking bond, in terms of size. Not content with issuing the largest bond in Russia’s history in 2002, it went back to the market for seconds in February with a three-year Rbs10bn ($351m) bond with an 8.1% yield.

The company is taking advantage of the improving climate on the domestic market to restructure its liabilities, retiring some of its short-term debt of Rbs387.2bn and increasing the long-term debt, which stood at Rbs455.9bn at the end of last year.

State-owned oil pipeline monopoly Transneft is also hoping to tap the market with an even bigger Rbs12bn bond in March, which has been delayed from last year. Likewise, Planeta Finance – a food and agriculture group that is controlled by oligarch Roman Abramovich – and supermarket operator Seventh Continent are also planning to relaunch stalled plans to issue Rbs3bn and Rbs1.5bn respectively in the next few months.

Demand grows

The impressive results are partly due to the low base from which the market has started. Russia’s corporate bond market is worth only 9% of all rouble bank credits to companies, themselves a pathetic 4%-6% of all invested capital. However, the bond business is shared by a handful of commercial banks and makes up as much as a fifth of some of the bigger commercial banks’ credit portfolios.

Even if the base is low, there could hardly be a better time for issuing bonds. Russia is running a record trade surplus, the Central Bank of Russia’s (CBR) gross international reserves passed an historic $80bn in January and yields have fallen well below inflation, which ended last year within the government’s target of 12%. Economists are expecting all these numbers to improve further this year. As confidence grows in the government’s ability to keep inflation to 10% by the end of the year, bond yields of between 7% and 15% – blue chip bonds are already yielding negative real interest rates – look increasingly attractive. Demand for new issues will easily outstrip supply, say bankers.

“The attitude of companies to bonds is changing and they are now seen as a viable way of getting access to relatively cheap and longer-term funds,” says Kieran Donnelly, head of fixed income at MDM.

The gloomy global investment climate has also been adding fuel to Russia’s capital market growth, which offers investors the almost unique combination of high yields and falling risk (see article on ratings, page 73).

In the past eight months, the dollar has fallen against both the euro (which is now the hard currency of choice for both average Russians and the CBR) and the rouble. “Investors have been selling their dollars to buy rouble assets, which has also pushed prices up and yields down. The falling return on the bonds has been balanced against the 18% real appreciation of the rouble against the dollar last year, and investors are expecting the dollar’s slide to continue,” says Mr Zimin.

Marketing ploy

Bankers have been riding a wave of liquidity but life is becoming more difficult: competition is growing even faster than the market and bankers have to work hard for their commissions.

With more issuers to choose from, investors have become picky about what they buy. And companies planning to issue a bond have a dozen lead managers to choose from. “These have become products that are sold, not bought,” says Mr Kotcherguine.

MDM’s team is courting business actively: travelling out to the regions to track down what it calls the emerging blue chips – the companies that were the engine of Russia’s 7.3% GDP growth in 2003. This courting process even includes various product departments combining to form the MDM ice hockey team, which takes on local teams during visits.

The market has dictated a more proactive approach. Sitting about on the trading floor earns banks small profits because demand has pushed the premium on primary issues trading on the secondary market down to rock bottom.

Sea change

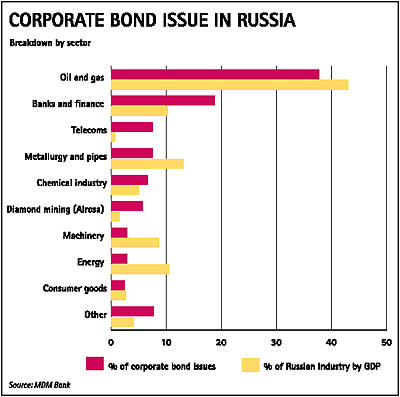

On the other side of the coin, about 10 companies account for about a third of the domestic debt market, both in terms of size and number of bond issues. Bankers have steered away from second tier companies until recently but the need for financing and the appeal of bonds has led to a sea change in managers’ mentality.

“There is stiff competition among the banks – both foreign and domestic – for the top 50 Russian companies, which already know what they want: they don’t ask for help in issuing bonds, they ask for a price,” says Mr Donnelly. “When you go to the smaller emerging blue chips, you find a sophisticated management running the company but they are not so strong on finance. Among these companies, we are seeing more disclosure, more willingness to open up to get access to more investment capital.”

While Russia’s household names are already as financially savvy as any billion dollar multinational, Mr Donnelly says that the vanguard of 20-30 up-and-coming Russian companies – typically with sales in the hundreds of millions of dollars – are already aiming at international market issues where rates are lower and the money longer.

There are still huge holes in Russia’s market and all the leading commercial banks are expecting dozens of new companies to appear each year, hungry for investment capital.

Dangers on the road

The market is still small, young and concentrated, though. Despite the ice-skating efforts of marketeers at banks like MDM, the bulk of bond issues have come from a small number of big companies. And, despite the record-breaking bonds from the likes of Gazprom and Transneft, most bonds are a only worth a few hundred million roubles (tens of millions of dollars) and have very short maturities.

Russia has yet to suffer its first default, so the yield curve, which bankers use to assess risk and price bonds, is still hypothetical. As big bonds are so concentrated among a handful of companies and most of these bonds are held by a handful of banks, a default could lead to a credit crunch and push a heavily exposed bank into serious liquidity problems. Another problem is that companies are issuing relatively short-term bonds to finance longer-term investment programmes. This mismatch poses problems for the issuers.

However, as liquidity in Russia has risen every year since 1998, this risk is fading. “There is a risk of a corporate bond default but this is not at high as it was in 2000,” says Mr Donnelly.

Close to the edge

Russia has already had one close call, when Gazprom put big petrochemical manufacturer Sibur into technical bankruptcy as part of a corporate control battle in 2000. Sibur had issued two bonds but Gazprom stepped in and paid them both off, avoiding a default.

More recently, there have been concerns about Moscow Bread Kombinat’s bonds that have been trading at 17 kopeks to the rouble (100 kopeks = Rb1). However, the bonds are small and almost entirely held by the Bank of Moscow, which is in turn controlled by the Moscow city government, which owns the Kombinat. The market has been unphased, however, regarding the decision to issue bonds as a political choice by the city to save one of its struggling dependents.

Perhaps the most realistic danger that Russia’s bond market faces is a general economic slowdown caused by the continued rise of the rouble against the dollar. This could lead to domestic producers that are still trying to build up their production facing crushing competition from importers.

“The rising strength of the rouble is a problem for producers and it could eventually check growth,” says Mr Donnelly. “But these are problems that all emerging markets face. We have to go through our growing pains like everyone else.”