The Cyprus financial crisis in March 2013 could hardly have come at a more alarming time for Greek banks. The troika of the European Commission, European Central Bank (ECB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) had set Greece a deadline of April 2013 to begin recapitalising its own banks, ravaged by the 2012 Greek sovereign debt restructuring. Failure to find private investors to commit fresh money equivalent to at least 10% of the capital base would result in full nationalisation.

Editor's choice

To make matters worse, Paul Koster, the Dutch head of Greece’s bank bail-out vehicle, the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund (HFSF), resigned for personal reasons in March 2013. Within days of walking through the door, his successor Anastasia Sakellariou, a former Credit Suisse investment banker, had a further problem in her in-tray. Troika officials privately warned the management of two of the country’s top four banks, Eurobank and National Bank of Greece (NBG), that their planned merger was unwelcome, and would not be eligible for the international financial support package.

“The legal merger could not be completed in time for the end-of-April deadline to begin raising capital, so the banks had asked for an extension to June before commencing the recapitalisation, but the programme framework would not allow an exception,” says Ms Sakellariou in her first interview since taking charge.

Eurobank executives decided it would be impossible to raise private money before the troika deadline, and the bank was duly nationalised, with the HFSF now holding just under 94% of its total shares. The HFSF now aims to create four roughly equal banks, and so chose to transfer the remains of two other nationalised banks, Proton and Hellenic Postbank, to Eurobank in mid-2013.

“Strengthening of the capital base is one of the management’s top priorities and several capital-enhancing initiatives are already under way, such as the introduction of the internal ratings-based risk weighting methodology for the newly acquired banks and a review of non-core participations. As it was wholly recapitalised by the HFSF, Eurobank has a unique strategic objective of attracting private sector capital no later than March 2014,” says Christos Megalou, chief executive of Eurobank.

First hurdle cleared

Remarkably, the other three banks were able to meet the deadline, and executed successful private capital raisings during May 2013. Two of the banks, Alpha and Piraeus, were assisted by capital injections from acquisitions of other banks. Alpha acquired Emporiki from France’s Crédit Agricole. Piraeus mopped up the healthy assets of Agricultural Bank of Greece, Geniki from France’s Société Générale, the Greek subsidiary of Portugal’s Millennium bcp, and three subsidiaries that Cypriot banks Bank of Cyprus, Laiki and Hellenic were required to sell as part of the Cyprus bail-out.

Effectively, the foreign banks were willing to pay to shed their Greek subsidiaries, in order to encourage their own investors to rerate stock prices and bond spreads. Emporiki was sold for a symbolic €1, and in the second quarter of 2013 Alpha recorded a goodwill gain of €2.6bn on the acquisition.

That left NBG to raise more than double the sum from the market that each of the other two banks needed, a total of €1.1bn. Only €100m of this came from hedge funds, and NBG chose not to employ an outside investment bank to manage the sale.

“We were going door-to-door among our clients and retail customers, any local or international players who had been shareholders of NBG, and a great many stepped up,” says Petros Christodoulou, deputy chief executive of NBG.

Popular warrants?

The HFSF now owns 84.4% of NBG, 83.7% of Alpha and 81% of Piraeus. A key element in selling the three rights issues was the decision to attach warrants – one for each share – that will give investors the right to nine shares held by HFSF at a later date. Jason Manolopoulos, chief investment officer at Swiss-based Dromeus Capital, was one of the investors convinced by this structure. “The warrants are a very asymmetric trade where each dollar invested gives you a potential seven dollar upside, I cannot think of a similar situation,” he says.

Inevitably, the idea of EU bail-out money subsidising Swiss fund managers attracted criticism in Greece and beyond. But Ms Sakellariou says the warrants were a key part of a delicate balancing act.

“Clearly, the warrants are not in the HFSF’s financial interest because we will not share in the upside. But on the other hand, if there had been no warrants, there would have been no deal, as investors were being asked to underwrite negative equity positions in an uncertain environment. During the course of the next couple of years, we hope that the market will support the execution of the warrants to give us a predetermined route back to the private sector for the three banks,” she says.

The composition of new investors supports that pragmatic view, according to Spyros Filaretos, chief operating officer of Alpha Bank, who says the bank’s new investor base is equally divided between retail and institutional investors, whereas institutions previously accounted for only 30% of the total. “Many of those institutions are foreign investors who are able to contribute new money by exercising their warrants, and they will stay with us if we deliver shareholder value for them,” he adds.

Tackling bad assets

Delivering shareholder value will have to start with addressing the non-performing loans (NPLs) that have now risen to 24.5% of total loans. The advisory arm of asset management giant BlackRock is now surveying asset quality and capital needs in the country, and is expected to report its findings at the end of October 2013. Despite the economic challenges, the three banks still under private control do not expect to tap shareholders for further capital when the BlackRock study is released. Mr Manolopoulos at Dromeus agrees with this assessment.

“From our research on the ground, we believe there was some deliberate non-payment when it appeared possible that Greece would leave the euro, as people hoped to force drachmaisation that would heavily reduce the euro value of their debts. As the economy stabilises, we are likely to see recoveries improve on NPLs, especially as there is so much hidden cash in the Greek economy due to decades of widespread tax evasion,” he says.

Moreover, the May recapitalisations were designed to give the banks very high capital adequacy ratios by EU standards – almost 14% in the case of Alpha and Piraeus, although less for NBG. By Mr Manolopoulos’s calculations, the capital positions of Alpha and Piraeus should be able to withstand the 40% peak in NPLs that he is projecting for 2014.

Even if the capital position is strong enough, there is still a strategic question about whether Greece needs to implement a 'bad bank' solution similar to those in Ireland and Spain. Anthimos Thomopoulos, deputy chief executive of Piraeus Bank, says Greece is distinct from Ireland or Spain because the crisis was caused by excessive sovereign rather than private sector leverage.

“If we can resolve the public sector financial position, then private sector collateral values will stabilise and a bad bank will not be essential. But it may be worthwhile if it incentivises banks to deleverage in a measured way and to avoid amending and extending troubled loans forever,” he says.

A new plan

The heavy NPL burden does not appear to be distracting managers from the crucial task of redefining their business model. For Piraeus and Alpha, the integration of their acquisitions allows ample opportunity for cost savings. Piraeus plans to close 250 branches across Greece by the end of 2013, at a rate of one per day, and has a voluntary redundancy programme set to reduce its Greek workforce by 12%. All the acquired brands will be absorbed into the Piraeus name except for Geniki.

“We want to see Geniki evolve as an independent financial institution specialised in servicing troubled assets for banks and institutional investors, and having a more active role in corporate finance advisory, particularly restructuring and recovery, and we will consider spinning it off for a sale. That project will begin in late 2013 or early 2014,” says Mr Thomopoulos.

Inevitably, the European Commission’s Directorate General for Competition (DG Comp) is in discussion with the Greek banks over what divestments they must make to comply with EU state aid rules. Ms Sakellariou sees her role as “to some extent a facilitator between the DG Comp and the banks, to fine-tune the balance between the burden-sharing required by DG Comp, and the desire of banks to safeguard a strong presence in the new banking environment”. She emphasises that all four systemic banks will draft their own restructuring plans for EU approval – even Eurobank, where the HFSF now has full ownership and has appointed new management.

“Our scope is to return the banks to the private sector in the best and fastest way possible. Our aim is to be at arms-length, we believe in the management of the banks who have pulled their institutions through exceptionally difficult circumstances. Our next programme requirement is to begin returning Eurobank to the private sector. The choice of myself, with an investment banking background, to head the HFSF is a clear statement of intent,” she says.

Portfolio management role

However, Ms Sakellariou will also need to take account of the HFSF’s position as a de facto portfolio manager who owns the entire Greek banking sector. This is especially true in the case of the south-east European networks held by all four banks, with the DG Comp expecting divestitures of subsidiaries deemed non-core. Alpha Bank has already sold its Ukrainian subsidiary to a local player (appropriately called Delta Bank), but all the Greek banks are wary about selling subsidiaries in the Balkans at capital-destroying prices.

“We need to look at the big picture and our role to maintain the investability of the banking sector. Some repositioning of the footprint of the international subsidiaries will need to take place, we will have to balance the DG Comp burden-sharing with value creation. That value creation will come from differentiating the stories among the banks, with some more domestically focused, others more international,” says Ms Sakellariou.

Logically, Piraeus would be a candidate for domestic focus, with its acquisitions catapulting it from a distant fourth to become the largest bank in Greece. Mr Thomopoulos agrees that it makes more sense to focus capital on the Greek market, now a concentrated industry, rather than in the crowded Balkan markets where Greek banks face competition from western European players with lower funding costs. Piraeus is likely to reduce the Balkan network and focus on fewer jurisdictions – particularly Albania, in view of 750,000 Albanian expatriates living in Greece – as well as limiting the product lines offered outside Greece.

At the other end of the scale, NBG enjoys profound benefits from its ownership of large Turkish subsidiary Finansbank, which generated pre-tax profits of more than $1bn in 2012. A plan for NBG to offer a 20% stake in Finansbank on the stock market was postponed in 2011 as the eurozone crisis hit valuations. Mr Christodoulou says that plan will be revived when the time is right. There are indications the DG Comp will require the sale of up to 40%, but it seems likely that NBG will want to maintain control of such a lucrative subsidiary.

Differentiating the Greek banks in Greece is more difficult. All are expecting a very slow recovery in retail lending, commercial real estate and businesses that focus on the Greek consumer. All are keen to lend into the improving performance of export-led areas such as shipping services, agribusiness and tourism. Even so, Mr Filaretos is confident that there will be room to grow as the economy stabilises.

“The consolidation resulting from the financial crisis has left fewer, more efficient players, both in the banking sector and among its clients. There will be competition for good customers, but based on rational decision-making and careful capital allocation, which was not the case before 2008 when the behaviour of many marginal players was compressing lending spreads below 1%,” he says.

Sovereign shadow

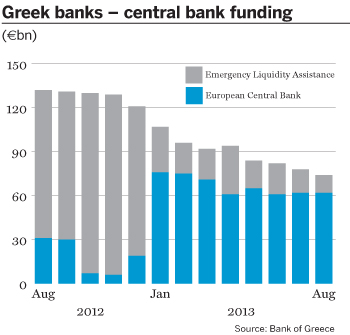

One key element to improving net interest margins is the revival of normal funding for Greek banks. Reliance on the expensive Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) for banks that do not have adequate collateral to fund through the ECB has declined substantially since the start of 2013 (see chart). Depositor confidence is returning, cutting the cost of deposits by well over 100 basis points. Piraeus has exited the ELA altogether and attracted €34bn in new deposits since the start of 2013, while the group loan-to-deposit ratio for NBG is down to 102%. The DG Comp appears to target 2017 for Greek banks to end the use of ECB funding, and bankers hope to beat that target comfortably.

“One very important factor will be the timing of Greece and its banks restoring access to the bond markets. Various officials have indicated that, if all goes well, Greece should be able to return to the markets toward the end of 2014, and that would signal 2015 as the year that Greek banks can go to the market, which will also reduce ECB funding,” says Mr Filaretos.

In short, Greece’s banks are already doing just about everything possible to return to sustainability. But their fate remains tied to the country’s fiscal adjustment programme and sovereign creditworthiness. There has been speculation that some of Greece’s official debts will need to be written off to return the country to fiscal sustainability. But Mr Manolopoulos believes maturity extensions and interest rate reductions would be more acceptable to the creditor nations than principal haircuts.

Mr Christodoulou says any discussion of official debt forgiveness will have to wait until the current troika loan disbursements are completed in 2014. He has as good a grasp of the situation as anyone – he was head of the public debt management agency during the vital period of sovereign debt restructuring from 2010 to 2012.

“The current coalition government has been much more stable than expected owing to the fear of political extremists gaining power. But there will need to be signs of growth before the European elections in May 2014, otherwise there is a risk of reform programme fatigue,” he warns.