Bahrain has prided itself on being the financial centre of the Middle East for more than 30 years. The outbreak of civil war in Lebanon in 1975 saw an exodus of bankers and capital looking for a new place to set up their operations, and Bahrain's capital, Manama, seized the opportunity.

Editor's choice

The tiny island state subsequently carved out a reputation for having the best financial regulation in the Middle East and highly skilled local staff, and fast became a magnet for banks looking to capitalise on its superior access to Saudi Arabia, the region’s biggest market. Today, more than 400 financial services firms are active in the country, including 24 retail banks, 27 Islamic banks and 32 wholesale banks.

Challenging times

In recent years, however, this status has been increasingly challenged by the establishment of financial centres in both Qatar and Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, with the latter being Bahrain's most well-publicised rival. The Dubai International Financial Centre, a free zone governed by the Dubai Financial Services Authority, was established in April 2006 and today hosts about 300 institutions. Meanwhile, the Qatar Financial Centre was set up in March 2005 and is home to 77 institutions.

The perceived attractiveness of Bahrain’s banking sector has taken a further hit this year in light of the domestic political turmoil, which has plagued the country since the first staging of Shi’ite protests on February 14. Several weeks of pro-democracy protests were finally quashed after troops from neighbouring Gulf states, including more than 1000 Saudi Arabian troops and about 500 UAE police officers, were sent to assist Bahraini forces on March 14. The following day, the king of Bahrain, Hamad bin Isa Al-Khalifa, declared a three-month state of emergency.

For a state that has long thrived on its reputation as an expatriate-friendly, stable and tolerant environment, its appeal has undoubtedly been tarnished by events this year. At least 13 protesters and four policemen were killed, while hundreds were injured in the clashes that gripped the country throughout February and March. The towers of the Financial Harbour were shrouded in tear gas as police battled with protesters and bankers found themselves unable to access their offices because of roadblocks and gangs of armed citizens.

Series of blows

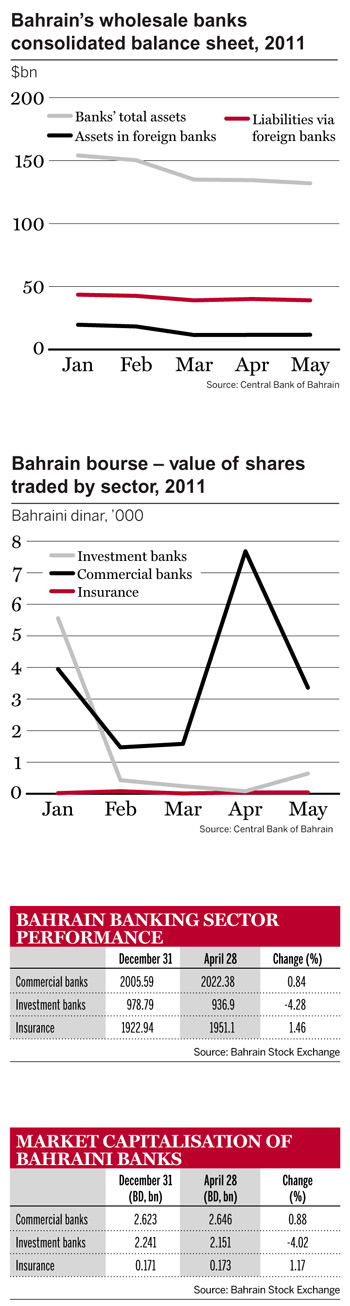

While only a few days’ work was actually lost – both HSBC and Standard Chartered closed their branch offices for just one day – the country’s financial credentials have been badly shaken. Bahrain’s cost of borrowing hit a new high on March 15, with the yield on its nine-year international bond reaching 6.84%, while the volume of transactions on the Bahrain bourse collapsed in the first quarter, falling by 52% year on year. Wholesale banks reported a 10% decline in total assets to $134.9bn during March, their lowest level since 2005, and assets in foreign banks, as well as liabilities via foreign banks, also recorded notable declines.

Arguably, the biggest blow to Bahrain's performance this year, however, was the downgrading of its sovereign rating by all three major international rating agencies: Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (S&P) and Fitch. This resulted in all local banks being downgraded.

“The downgrading of Bahrain’s sovereign status automatically had an impact on banks’ cost of funding,” says Robert Ainey, chief executive of the Bahrain Association of Banks (BAB), established in 1979 by ministerial decree to promote the country overseas as an international finance centre. “Investors who were funding Bahrain began asking for a higher rate to cover what they saw as a greater risk. So it became more difficult for the banks to borrow money.”

The hike in the cost of funding for Bahraini banks is expected to translate into higher costs in their lending and an overall increasing burden on the clients. More worryingly for the banks, it is likely to eat into their profit margins this year.

Further complications

Banks’ profitability is expected to be further weighed down by a spike in non-performing loans (NPLs) due to the disruption to business activities in February and March. The Bahrain Chamber of Commerce estimates that the losses incurred amount to about $2bn, although this figure is likely to increase as the country continues to feel the effects of its recent turmoil for some time.

The retail sector was especially badly hit, which led to severe cashflow problems, while a good number of employees from large private and public institutions also lost their jobs. According to some authorities, up to 8000 Shia workers were fired or suspended for taking part in the protests.

Consequently, industry insiders predict it will become increasingly difficult for customers to repay both business and consumer loans from banks. In turn, they will have to increase provisions over the next couple of quarters to account for these rising loan defaults.

“Banks are expecting an uptick in NPLs during the second and possibly third quarter of this year because a lot of people lost their jobs during the unrest,” says Mr Ainey. “The central bank believes the third and fourth quarters will be the true test for seeing how well things will bounce back.”

Property crash

The weak domestic real estate market is expected to further compound the problem of NPLs. In a report published by S&P on July 4 entitled ‘Trends and events affecting banks in the Gulf in 2011’, the rating agency notes that “it is possible that we’ll see a further drop in real estate prices in Bahrain”.

“On a system-wide basis, but especially for retail banks, we expect a deterioration in loan quality due to their exposure to commercial real estate,” says Goeksenin Karagoez, a credit analyst at Standard & Poor’s. “At the end of March 2011, retail banks’ exposure to this riskier segment stood at one-third of gross loans, which is pretty high.”

Assets of Bahraini banks started to fall after the regional property crash in late 2008. In particular, its investment firms posted steep losses in the wake of the crash. “Investment banks were hit the most because of their very high exposure to real estate,” says Mr Karagoez. “Their business model has now become inefficient.”

Much of Islamic investment bank Arcapita’s income came from upfront fees on transactions on behalf of asset management clients during the regional real estate boom of 2005-08. But those transactions dried up as the regional economy deteriorated and the property bubble burst, sending both asset values and revenues tumbling. It posted a loss of about $560m for 2010, following a net loss of $87.9m the previous year.

Bahraini competitor Gulf Finance House, another Islamic investment bank, was also unable to find new revenue sources after its similar business model collapsed with the property crash. It posted a loss of $728m in 2009 and $349m in 2010.

“The Islamic banks have been impacted by the fact that up to 80% of their exposure was to the real estate sector,” says Patrick Gallagher, chief executive of HSBC Bahrain. “There aren’t any big real estate trades taking place right now and property prices have softened further this year so banks are going to have to take that into account.”

Khalid Howlader, senior credit officer at Moody’s, echoes this view. He says: “Bahrain isn’t the deepest real estate market and the unrest will have had a further knock-on effect on both commercial and residential property prices.”

Business as usual

While there is no doubt that the unrest this year has damaged investors’ confidence, bankers on the ground insist that life in Bahrain has moved on and business is now continuing as normal. “We are now seeing business volumes similar to the levels seen in mid-2010. Based on that metric, I’d say things are back to normal,” says Mr Gallagher. “We’ve come through a hiatus but overall its long-term impact on business has been minimal. Certainly, the top tier of banks are operating well today and have posted some good numbers for the first half of the year.”

Indeed, Gulf International Bank posted an annualised 11% increase in half-year profit to $62.4m at the end of June, while Ahli United Bank reported a 19% rise to $161.7m and Arab Banking Corporation announced a 55% increase in net profit to $116m over the same period.

“The unrest did affect the cost of funding, principally for the unlisted banks, but that has improved a fair bit over recent months,” says Mr Gallagher. “We have seen credit default swap [CDS] spreads come back noticeably in the past two to three months. We’re now back to about 50 basis points [bps] wide of where we started the year so the gap has been narrowing quite rapidly given the spreads widened by 120bps when the crisis kicked off.”

Bahrain’s CDS (a form of insurance which protects the buyer in the case of a loan default) spreads are currently trading at about 225bps to 230bps, roughly 140bps inside Dubai.

Positive news?

On July 20, S&P removed Bahrain’s ratings from credit watch negative, citing eased political tensions and expectations that increased public spending will lift economic growth next year. However, at the same time, S&P assigned a negative outlook to the long-term ratings owing to the fact that the “spectre of renewed political turmoil could result in weaker economic performance than in our base case expectations”.

Many industry players think there is still a noticeable disconnect between where the ratings stand today and the current CDS spreads, which are showing a marked improvement in the economy.

“I think we’ve been unfairly characterised. We were downgraded three notches by Fitch while other countries such as Tunisia and Egypt were only downgraded by one notch,” says Mohammed Bin Essa Al-Khalifa, chief executive of Bahrain’s Economic Development Board. “The one thing that an agency has to rate is the risk of default and that has gone down. There is a growing appetite for Bahraini bonds so I’m not happy with the ratings.”

Outcome awaited

But while the economy has shown signs of recovery, many believe that the effects of the turmoil will take a while to fully trickle down and will not become clear until the dust has fully settled.

“Obviously, there will be a lag effect between the events and their impact on the economic environment,” says Mr Karagoez. “It is unclear how the banking sector will perform in the third and fourth quarter of this year. I expect it will vary hugely from bank to bank. The first half figures of onshore and offshore banks do not suggest an immediate asset quality impact, but on a system-wide basis, the customer deposits from abroad posted a significant drop.”

In April, the International Monetary Fund cut its forecast for economic growth this year to 3.1% from an earlier projection of 4.5%. The following month, Standard Chartered lowered its initial 4% estimate to 3%, likely to be the lowest growth figure among the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) states this year.

“There’s no doubt that the Bahrain Inc brand took a hit from what happened in February and March and it’s going to take time and effort to regain international investors’ confidence,” says Mohammed Chowdhury, head of Arcapita’s financial management group. For a country that earns roughly 25% of its gross domestic product from the financial sector, regaining that confidence and addressing its market challenges is of enormous importance.

Reform and recovery

Clearly, any recovery going forward is critically dependent on maintaining social peace and political stability. Consequently, the outcome of the National Consensus Dialogue – talks that began between pro-government and opposition groups on July 2 – is eagerly anticipated. Aimed at healing the deep rifts that have opened up this year, the talks are intended to focus on reform, with the aim of reaching consensus on how to achieve it.

“What we’re having is a debate about the speed of reform. Everyone agrees on the direction, but some people want to move faster and others more slowly and you see this in the range of debates,” says Mr Al-Khalifa. “The dialogue will come out with a list of recommendations which will definitely be a step forward in Bahrain’s development. There will be more accountability and transparency, more employment opportunities for women, more housing and so on.”

In contrast to this optimism, Bahrain's opposition has expressed doubts about whether the dialogue can bring about any serious change, noting that it only has 35 of the 300 seats at the bargaining table. On July 17, Bahrain’s main opposition party, Al-Wefaq, withdrew from the dialogue, claiming the talks are “not serious”.

“The political dialogue has been very slow and we have seen only minor progress,” says an industry insider who asked not to be named. “It has ended up being more of a talking shop – the list of agreed items is pretty scant.”

In March this year, the GCC pledged $10bn in aid to Bahrain to be spent over the next decade. Such a vast sum has the potential to substantially boost Bahrain's growth, employment and stability, but so far little has been heard of how it will be distributed.

Such protracted political and economic uncertainty will negatively impact upon the country's operating environment, and of course, its banks’ performance.

However, many of the factors that allowed Bahrain to emerge as a regional financial hub – its small size, cheaper operating environment, proximity to Saudi Arabia and good regulation – remain intact. By regrouping and redoubling their efforts, policymakers can re-build investor confidence and shift the spotlight back on Manama’s many strengths.