Despite its healthy oil revenues, Kuwait’s economy was hit hard by the global financial crisis and it suffered the worst recession of all the Gulf countries in 2009. The Kuwaiti authorities were forced to guarantee all deposits at local banks in 2008 after Gulf Bank made headlines in October that year when it was hit by steep derivatives trading losses amounting to Kd375m ($1.35m), before being rescued by the central bank, which subsequently halted Gulf Bank's trading operations.

Kuwait also became synonymous with high-profile losses and defaults at its investment companies. Global Investment House, Kuwait’s largest investment bank, defaulted on $2.8bn of debt, while The Investment Dar (TID) became the first Gulf company to default on an Islamic bond in May 2009 when it missed a payment on $100m of debt. TID had Kd1.08bn of total debt outstanding as of September 2008. In total, the investment sector hemorrhaged more than $2bn in 2009, following a loss of upwards of $3bn in 2008.

The Kuwaiti government sought to bolster the financial sector through the introduction of the Financial Stability Law in May 2009 with the threefold aim of shoring up banks, productive sectors and troubled investment companies in order to restore confidence and revive credit growth. But it has had limited success. Rising non-performing loans (NPLs) and associated heavy provisioning has led most banks to exercise caution and protect their market share, rather than compete for new customers.

Nowhere to lend

A dearth of lending opportunities in the wider economy has further impeded Kuwaiti banks’ efforts to revive loans. Credit growth recorded a nominal year-on-year increase of 2.1% in November 2011, while system-wide banking assets stood at Kd43.5bn in November 2011 – a year-on-year rise of 4.5%. Almost half of the increase came from liquid assets, deposits with the Central Bank of Kuwait (CBK) and CBK bonds.

The banking sector’s average loans-to-deposits ratio stood at 73.7% in 2011, significantly lower than the 85% mandated by CBK. The latest figures released by the CBK show that in January 2012, private sector credit growth was up by a marginal 2.3% on a year-on-year basis – the slowest pace since August 2011. In 2008, private sector credit growth exceeded 20%.

“We would love to be doing more lending but I do not think there will be demand for loans going forward,” says Gulf Bank’s chief general manager and chief executive officer, Michel Accad. “Borrowers are reluctant to take loans because of the prevailing uncertainty in the market and their aversion to risk. The appetite for borrowing has reduced enormously since 2009 and we are in a worse operating environment today than we were in 2008."

In February 2010, the government approved a five-year $130bn economic development plan (EDP) aimed at diversifying Kuwait’s oil-based economy and turning the country into a regional trade and financial hub. With an estimated 9% of world crude oil reserves, petroleum accounts for nearly half of Kuwait’s gross domestic product.

The EDP outlines a total of 1100 projects, with a particular focus on what have been termed ‘mega projects’, which include a $77bn business hub called Silk City, a $10bn metro system, $3.5bn of investment in Kuwait International Airport and multi-billion dollar healthcare and education schemes.

Boon or bust?

The EDP was expected to serve as a boon for the banking sector, with the government providing 50% equity and the remaining half to be financed by the banks. But while banks are queuing up to fund the schemes, the fractious politics between the parliament and government means there are continued bottlenecks in awarding projects, and designs keep being returned to the drawing board.

“Contracts are being awarded six months later than planned,” says Gulf Bank’s Mr Accad. “We are now in the third year of the plan and in my opinion, what was expected to happen in five years will take 10 years. It is progressing too slowly for the economy to pick up.”

The government has continued to undershoot its spending targets on the plan, achieving an estimated 60% of its targeted Kd5bn infrastructure expenditure in the fiscal year 2010/11. With few other lending opportunities in the market, banks have been relying on the EDP to drive balance sheet growth. Gulf Bank, for example, is helping finance four key projects – the Kd1.04bn Jaber Al Ahmed bridge, the Kd436m Sabah Al Ahmed residential city, the Kd303m Jaber Al Ahmad hospital and a power plant.

“These four projects are all happening but at a much slower pace than planned,” says Mr Accad. “I am hopeful but not optimistic that loan growth will pick up [in 2012]. The election of the opposition to parliament is more likely to hinder than help progress.”

Political worries

In February 2012, Kuwait called a snap election after the country's emir dissolved parliament following youth-led protests and bitter disputes between MPs and the government. The opposition – a loose formation of Islamists, nationalists and independents – secured 34 seats in the 50-member parliament. Political parties are banned in Kuwait but several political groups operate freely.

National Bank of Kuwait (NBK), the country’s largest lender with assets of Kd13.6bn at the end of 2011, which accounts for 50% of the country's banking sector's assets, is more upbeat about the situation, while also acknowledging hurdles remain.

“Although there are some delays in government spending, we are seeing some signs of improvement and we believe that spending will pick up,” says Ibrahim Dabdoub, group chief executive of NBK. “The problem we face is implementation. Experience tells us that such programmes in Kuwait take at least two years before they pick up momentum, and indeed we are now seeing the first mega project being awarded – the Al-Zour IWPP – almost two years after the launch of the plan.”

While the booming oil sector makes for stellar public finance figures, it is precisely this lack of diversification in the economy that led banks to pile into lending to real estate, investment companies and the stock exchange. At the onset of the crisis, total credit extended to investment companies and the real estate and construction segment was estimated at 11% and 25%, respectively. This overexposure has seen them plagued by substantial impairment losses.

Thankfully, bank loans to the property market saw an improvement in 2011, growing a decent 4.8%, helped considerably by the uptick in real estate sales; total sales grew by an annualised 35% in 2011 to Kd2.7bn, with the investment sector constituting the leading segment at 53%.

In January 2012, real estate sales hit Kd318m, a rise of 64% on the same month in 2011. While this level of demand is unlikely to be sustained throughout the year, it should remain high.

Dead weight

The poor state of Kuwait’s 105 or so investment companies, many of which continue to post losses and undergo debt restructurings, continues to weigh down on banks’ credit growth figures. Lending to non-banks fell Kd65m in January 2012. The collapse in the value of their assets and frozen debt markets in the wake of the financial crisis left many without a way of paying off the loans with which they had financed their investments.

“Many [of the] investment companies in existence today are moribund. If some courageous decisions were taken there would be a lot of pain over the next couple of years and then it would all be cleaned up,” says Mr Accad. “But given past experience, my guess is that things will probably drag on much longer which will delay a full recovery. It is like the Japanese crisis – you can undergo a recession for 15 or 20 years because you haven’t addressed the problem in a very systematic manner.

"Frankly, I don’t think there’s any light at the end of the tunnel from now until 2015. Half of the investment companies today should not exist – they should be liquidated. If you want to be realistic then let a few go bankrupt, liquidate their assets and clean up the system. If they do that then in two years the problem can be behind us but I think politics will get in the way.”

Indeed, bankers are worried that investment companies will default or be forced into seeking bankruptcy over the coming months and years, while other companies are making slow progress. TID’s implementation of its five-year restructuring plan commenced in June 2011. Some Kd82m will be paid out in the first year, which will go to individual investors and small non-financial institutions. In the subsequent years there will be fixed payments to the remainder of the banks and investors, followed by a final payment before June 2017. To partly finance this, TID may liquidate some $1.7bn of assets over the next three years.

Meanwhile, in December 2011, creditors of Global Investment House agreed to delay repayment of the principal of their debt to June 2012 so that the company can undertake a second restructuring after having completed a $1.73bn restructuring in 2009.

“Since 2008, local banks’ provisions have exceeded Kd2.4bn. Of course, not all of this is related to investment companies,” says NBK's Mr Dabdoub. “In comparison, local banks’ loans to all investment companies amount to Kd3.26bn, of which a small part is owed by consumer finance companies whose business model is unlikely to have caused significant damage with the onset of the crisis. Our analysts estimate that these cumulative provisions amount to 85% of banks’ exposure to potentially troubled investment companies. This is not a proper measure to go by, but it does provide you with a perspective on the issue.”

Varying health

International credit rating agency Fitch believes that impaired loans in Kuwait's banking system have peaked and that there will be a slow and gradual improvement in asset quality from now onwards.

NPLs are certainly declining, albeit at a steady pace. After having soared by a respective 153.97% and 84.38% during 2008 and 2009, they declined by 14.24% during 2010. Banks’ system-wide NPLs stood at 7.4% at the end of 2010 and the CBK forecasts this will fall to 5% by the end of 2012.

Of course, the health of banks’ loan books varies significantly. With an NPL ratio of 1.55% and an NPL coverage of 243% at the end of 2011, NBK’s asset quality is among the highest in the Gulf Co-operation Council countries. Excluding NBK, the NPL coverage system average for Kuwait's local banks would be 65% to 70%. However, Fitch notes that “impairment charges at some banks will remain high in 2012 due to the need to improve weak loan loss reserve coverage”. Furthermore, banks remain cautious.

“I have to be realistic – I look at the environment and I know some customers are still suffering,” says Mr Accad. “We cleaned out the NPLs off our balance sheet but new ones have since crept in because the economy started deteriorating again. We are expecting more loan defaults to come through but our aim is to reduce the ratio by 1% to 2% each year going forward until 2015.”

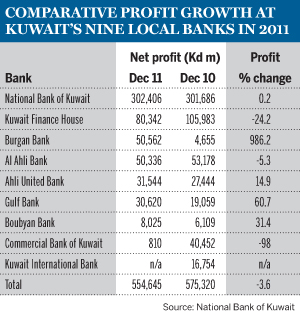

After peaking at 26% in March 2010, Gulf Bank’s NPL ratio fell to 15.6% by the end of 2010 and 10.7% by June 2011. It subsequently rose to just under 11% at the end of 2011. Meanwhile, Commercial Bank of Kuwait posted a sharp drop in annual net profit in 2011 to Kd810,000, down from Kd40.5m in 2010, due to the bank’s decision to allocate its operating profit as provisions against its loan and investment portfolios.

Commercial Bank announced an operating profit before provisions of Kd101.269m, an 8% increase from the Kd93.609m recorded in 2010. The bank’s NPLs stood at 6.7% of gross loans at December 2011, down from 15.4% at the end of 2010.

Recovery process

Slowly but surely, Kuwait’s banking sector is clawing its way back from the nadir of its fortunes in 2008 and 2009 when the sector was beset with problems. And amid the testing environment, there have been some bright spots.

Islamic banking has been gaining strong ground in the Kuwaiti market in recent years, undergoing double-digit growth during 2010, albeit from a low base. Islamic finance represents one-third of assets and deposits as of June 2011.

Aware of the strong growth prospects offered by Islamic finance, NBK’s strategy of diversifying into Islamic banking took further traction in 2010 with the lender increasing its stake in Islamic finance house Boubyan Bank to 47.3% from its previous 40% in 2009. It hopes to raise that stake further to 51% in the future. “Islamic banking in Kuwait is among our priorities and our stake in Boubyan was a very successful strategic move,” says Mr Dabdoub.

Adel Al-Majed, chairman and managing director of Boubyan Bank, says: “Six years ago, Kuwait Finance House was the only Islamic bank [in Kuwait]. Three banks have since opened, including ourselves, and Warba Bank, a new Islamic bank that started operating in early 2012.”

Indeed, aside from Boubyan Bank’s establishment in 2004, Kuwait International Bank gained permission from the country's central bank to operate as an Islamic bank from July 2007, while Bank of Kuwait and Middle East fully converted into an Islamic entity – Ahli United Bank – in December 2009.

“We are seeing the tendency of the young is to want Islamic finance,” says Mr Al-Majed. “And the evolution of Islamic products and services in recent years means a customer can get 99% – if not 100% – of what they need from Islamic banking today.”

Driving forces

As the smallest Kuwaiti bank, there is significant room for Boubyan to reposition itself. Its market share in terms of its financing portfolio stood at 2.34% at the end of 2009, before growing to 3.3% at the end of 2010 and to 4.05% by the end of 2011.

“We are aiming for 6% to 8% market share by the end of 2014," says Mr Al-Majed. "We initiated a new five-year strategy in 2009 that has proven successful for us so we are sticking with it. It is focused on high-net-worth individuals, affluent customers and we would like to be within the top two banks for corporate customers. We know that big corporates such as Zain telecoms will always go to the big banks such as Kuwait Finance House. We are looking at attracting mid-size companies. Our main challenge is that we cannot grow the bank as fast as we would like, [as well as] our branch network.”

Boubyan currently has 20 branches, just under one-third of that of Kuwait's largest Islamic lender, Kuwait Finance House, which has 54 branches. Boubyan aims to increase its network to 30 branches by 2014.

Excluding Islamic finance, it was consumer lending and personal facilities that continued to lead loan growth across Kuwait's banking market, registering a positive 8.2% increase year on year. Already-healthy consumer sentiment was boosted further by the large grant of Kd1000 per citizen from Kuwait's emir in February 2011.

“The consumer sector is quite healthy and this has been driving activity for the bank in recent quarters,” says Mr Dabdoub. “There are also untapped segments within the consumer sector that will prosper with improved economic activity... creating valuable opportunities for banks.”

However, business related loans continued to stagnate in 2011, up a mere 1%, and they still hinge on the pace of execution of the government’s EDP. Interbank rates fell by four basis points to seven basis points across maturities in 2011 as banks remained awash with liquidity. The one-, three-, six- and 12-month rates averaged 0.82%, 1.05%, 1.3% and 1.54, respectively. With deposit growth outstripping that of loans, capitalisation has improved across the sector.

Local constraints

While banks wait for domestic opportunities, their foreign assets have been growing. In January 2012, foreign assets held by local banks increased 14.3% compared to 2011. The lacklustre demand for credit has also seen them place large amounts back on deposit with the central bank in low-yielding assets, hence the drop in loans-to-deposit ratio from 98% at the end of 2009 to 73.7% today.

The central bank made no changes in official policy rates in 2011. The last rate cut was in February 2010 when it cut the discount rate, its key lending rate, to a record low of 2.5%. The weak operating environment is continuing to suppress banks’ appetite for loans and key systemic risks remain across the banking industry.

Provisioning against NPLs will remain a top priority for banks during the next 12 to 18 months and the debt overhang at investment firms will ensure banks steer clear of the sector. The slow implementation of the EDP means that credit growth in Kuwait will remain subdued in 2012 and profits depressed. All recognise that it is the country’s political inertia that is derailing the progress of the plan and that without it, there is little else to revive its stagnant banking market.

“Given our dominant position in Kuwait, our growth potential will be limited to the growth of the local economy,” says Mr Dabdoub. “Unfortunately, the outlook for the Kuwaiti economy has less to do with economic policies and programmes such as the [EDP] and more to do with the political dynamics that have been an obstacle to the implementation of such plans. If you put politics aside, all the fundamentals are extremely positive.”