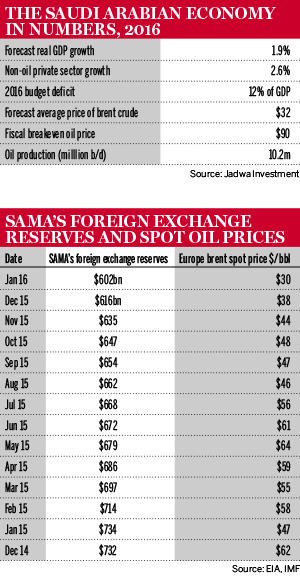

If Saudi Arabia was in need of a wake-up call to reform its economy, then the sub-$50-a-barrel oil price environment has done the trick. After a decade in which prices have averaged $86, according to data from the Energy Information Administration, the country is now coming to terms with the prospect of a new energy order. With downward pressure on oil prices likely to continue, the impact is already being felt. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects the Saudi economy to grow by just 1.2% in 2016, down from 3.4% in 2015.

For Saudi Arabia, these oil price movements matter. During a decade of stellar economic growth between 2003 and 2013, when oil prices were high, the country's economy doubled in size. But during this period there was a broader failure to achieve meaningful non-oil diversification of the economy. Oil receipts still account for close to 90% of government revenues, while the sector contributes about 45% to total gross domestic product (GDP). Though non-oil growth has ticked along well in recent years, it has been closely linked with government spending.

Now, a new impetus is dictating the country's diversification efforts and the vision for long-term change has begun to be translated into policy. “There is a sense of positive urgency and a mobilisation of resources towards action and execution that is very promising. It is something that is definitely needed,” says Tariq Al Sudairy, the chief executive of Jadwa Investment, a local investment and financial services firm.

Regional rivalry

Yet, this collapse in commodity prices has come just as a host of other challenges has emerged. Improving relations between the West and Iran have led to the lifting of key sanctions, opening up Iranian crude oil exports to the global market. Not only is this likely to compound the difficulties of managing oversupply in the oil market – the recent failure to achieve a consensus on a production cut by the world’s top exporters being a case in point – but it provides a much-needed economic and political boost to the country's main regional rival.

Meanwhile, in pursuit of a more robust foreign policy, the Saudi military is now engaged in a protracted conflict in Yemen. With the recent discussions over the potential deployment of Saudi troops to Syria, the country is not shying away from attempts to reimpose a sense of regional order. But this approach is coming at a cost: security and defence spending accounts for 25% of the 2016 budget, the largest single contributor to government expenditure.

Saudi Arabia is expected to post a deficit of 12.6% of GDP in 2016, while Standard & Poor’s expects an average deficit of 9% of GDP between 2016 and 2019. With a 2014 budget breakeven price of oil at $104 a barrel, according to the IMF, revenue and expenditure are now being closely scrutinised.

Infrastructure priorities

On the domestic front, a number of pressing developmental challenges will require substantial financing in the coming years. Large infrastructure developments in the housing and transport sectors, as well as the need to generate significant private sector job opportunities, are among the immediate priorities. Meanwhile, demographic pressures are mounting as a growing population, increasing life expectancy and high rates of non-communicable diseases challenge the existing healthcare infrastructure. Cumulatively, the country's spending requirements are growing just as oil receipts are dwindling.

Meanwhile, speculative pressure on the Saudi riyal’s peg to the US dollar mounted in 2015. Twelve-month riyal forward contracts reached multi-year highs in early 2016 as a result of the collapse in oil prices. By March, however, the worst of the volatility appeared to have subsided.

“Looking at the way the riyal-dollar forward market has moved it seems that SAMA [Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency] did intervene to defend the currency,” says James Reeve, deputy chief economist at Samba Financial Group, the country’s third largest lender by total assets.

“It is the hedge funds taking the short positions against the riyal and the local banks are taking the other side of the trade, and SAMA is supporting those banks with enough foreign exchange as necessary. SAMA isn’t blinking and neither are the banks,” he adds.

Daunting though these challenges may be, in Riyadh there is a keen awareness that such difficulties are accompanied by commensurate opportunities. Leading public and private sector figures speak of the changing suite of investment opportunities and the longer term potential on offer in a country that is engaging head on with the need to change and diversify its economy.

“I think this year will be reasonably good in terms of economic growth, and quite good for the banks. The budget is better than many people thought; it is very supportive. The non-government sector should continue to do well, especially in the retail and services space,” says Bernd van Linder, managing director of Saudi Hollandi Bank, the country's eighth largest lender by total assets.

A healthy balance sheet

Although the Saudi government’s plans for economic diversification failed to generate the kind of traction that was needed during the boom years, the authorities nevertheless handled the country’s finances prudently. Today, Saudi Arabia’s balance sheet is formidable; SAMA holds just over $600bn in foreign reserves, while outstanding domestic and international debt is among the lowest in the world. The country can also count on substantial assets abroad, while domestically the scope for privatisation of public assets remains vast.

“In terms of the fiscal financing, I think the government is in a strong position. By 2020 we have domestic debt at just 20% of GDP,” says Mr Reeve.

This careful management of the public purse puts Saudi Arabia in an excellent position to weather the current storm. Indeed, based on current oil prices the country could comfortably continue without any major restructuring for the next four to five years based on current expenditure. Accordingly, this situation of fiscal strength provides the government with an arsenal of possible policy responses to the current challenges.

In 2015, Saudi Arabia commenced a domestic debt programme, issuing about SR20bn ($5.3bn) per month since June. This is expected to be followed by the country’s return to the international debt markets, according to reports by Reuters. “Sovereign debt issuance abroad will account for about 11% of fiscal financing requirements over the next five years. But domestic debt issuance to local entities, including banks and pension funds, will be the dominant source of funding in tandem with the drawdown of foreign reserves,” says Mr Reeve.

This range of tools will be important and the Saudi authorities will need all of them if they are to maintain a favourable economic outlook. The launch of the National Transformation Plan, expected in the second quarter of 2016, will go a long way to addressing many of the structural challenges currently blighting the country. The question, as always, will be how these changes can be implemented and over what timeframe. If they are done right, Saudi Arabia could enter a new phase of stellar economic growth, but if they are not, the outlook will remain highly challenging.