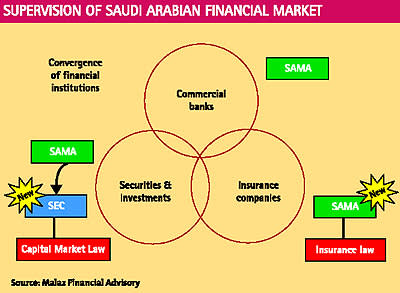

In 2003, the Saudi economy produced an exceptional performance on the back of $85bn in oil revenues, the highest in 20 years. The year was also exceptional because a new capital markets law and insurance law were approved, which could not only radically reshape the entire financial sector in the kingdom but also have a significant impact on financial services in the region, particularly in Bahrain and Dubai.

Saudi Arabia, the largest economy in the Middle East by far with a GDP of $189bn in 2002, has for decades been a magnet that has attracted bankers and financial institutions from across the globe. Given its massive oil wealth, bankers flocked in droves to get a slice of the action from both the government and the burgeoning private sector. The conservative Saudi authorities tried to keep a lid on the financial explosion taking place and, unlike many countries, maintained a strict limit on the number of licensed banks and only allowed some foreign banks entry as affiliates of domestic banks. Limits were also placed on non-bank financial intermediaries thereby limiting official activities in the securities, investment and capital markets areas.

Offshore growth

The restrictions and the lack of a broad regulatory and institutional infrastructure led to the growth of offshore banking in the Gulf, and in Bahrain in particular, from the early 1980s. Naturally enough, briefcase bankers became the norm in the kingdom to satisfy the growing demand for increasingly sophisticated financial products and services. Much of Bahrain’s offshore banking community, for example, existed to do business in Saudi Arabia because the regulatory framework was not there to handle the range of services demanded.

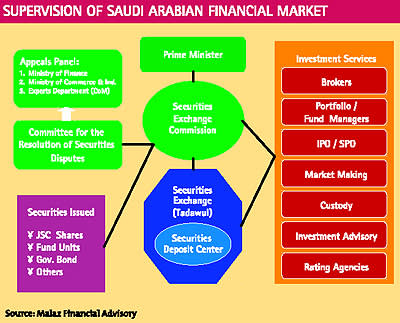

While it can be discussed at length why it has taken Saudi Arabia so long to enact legislation, the long-awaited capital market law (CML) was approved in June 2003. Although the appointments of the commissioners to run the institutions associated with the new law had still not yet been made as The Banker went to press, this delay only appears to be part of the slow Saudi bureaucratic process and announcements are expected very soon.

Historical leap

“The law is a significant qualitative leap in the history of the Saudi capital market,” said the governor of the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA), Hamad al-Sayari, in a recent speech. “The law will contribute to the restructuring of the kingdom’s capital market on new and sound foundations that broaden its base, enhance confidence in it, attract investments, and provide integrated regulatory reference to the market that includes the most important principles, foundations and provisions covering all aspects of the market.”

Coming at a time when the economy grew strongly, by 6.4% in 2003, the new law is seen as a springboard for further growth. “The new law will open up a number of business opportunities for Saudi banks, which should help to diversify their operations,” says Dr Nahed Taher, senior economist at National Commercial Bank, the country’s biggest bank. “Some of the emerging opportunities are full-scale brokerage services, private placements, initial public offerings (IPOs), dealing in the corporate bonds market, conversion of existing family businesses to joint stock companies, and facilitating mergers and acquisitions of private companies,” she says.

“At present there are 69 listed companies out of the total 119 joint stock firms. This implies that 50 joint-stock companies are still closed which are potential candidates for future stock market listing. Given the size of the Saudi economy, the potential is there for another 100 family-owned businesses to convert into publicly-listed companies. Once the Saudi entrepreneurs fully realise the benefits of regulatory liberalisation and the market potential for their business activities, financing arrangements and funding needs of businesses will open up opportunities for the banking industry,” says Dr Taher.

Many bankers are extremely bullish about the potential and are keen to get involved. SAMA is also in the process of approving new banking licences and the kingdom is opening up to a range of regional and international players. Bahrain’s Gulf International Bank has already opened a branch, Dubai’s Emirates Bank International is due to open in mid-2004, and National Bank of Kuwait and National Bank of Bahrain are both in the process of opening a branch.

But that is not all. SAMA says there are at least another six requests for licences from banks in the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) states in the pipeline.

International front

And the interest does not stop there: international banks have also been keen to gain a direct foothold and last October SAMA approved a branch licence for Deutsche Bank. The German bank will not be involved in retail banking and will focus entirely on investment banking activities. Dr Hans-Jurgen Koch, head of Middle East for Deutsche, told The Banker he expected the branch to be open for business by the last quarter of 2004.

Along with Deutsche, other global banks are preparing for the opening up of the Saudi capital markets, including HSBC. HSBC, which has a minority stake in Saudi British Bank, has been given approval to establish an investment banking operation under the new CML legislation. “We see huge opportunities for us in this market,” says Tim Gray who represents HSBC’s investment banking interests in the kingdom. Given HSBC’s synergies through Saudi British, the global bank is well placed to take advantage of existing relationships, especially in terms of IPOs and merger and acquisition activity. The new HSBC investment banking entity is expected to offer a full range of corporate advisory, debt capital markets, Islamic finance, asset management and brokerage services.

Bankers believe that many families want to spin off various companies but they do not want to lose control. They believe that the CML offers the ability to streamline many of their conglomerates and, with the high liquidity in the kingdom, the IPO market is expected to become a hive of activity.

HSBC and Deutsche are not the only global players interested. Once the appointments are made and the CML is operative, SAMA officials expect a number of big players to enter the arena. Many institutions are said to be just waiting until the law is fully operational before applying for entry. As officials note, licences will not come quickly; they could take 9-12 months to be fulfilled.

Market potential

The growth potential of the Saudi market appears huge. In IPOs – although they are virtually non-existent at present – many conversions to joint stock status are expected and analysts believe this will create a deal flow of 5-10 IPOs per year in the medium term, raising new capital of $2bn per year. A new domestic bank is expected to be formed soon, pulling together a number of well known exchange businesses and an IPO for this is expected to take place in the second quarter.

The government continues to stress its privatisation programme, especially following the successful launch of the Saudi Telecom Company last year, which attracted almost one million subscribers. It is expected that about 10-12 companies will be floated per year. The government’s huge stock holding through large investment funds and quasi-governmental entities is expected to be released to broaden public equity ownership. And, as part of this programme, a portion of NCB, the country’s largest bank in government ownership, is expected to be sold off during the next year, providing an attractive investment opportunity.

Analysts believe the corporate bond market in Saudi Arabia has massive potential. They estimate it to be worth $75bn if developed based on GDP multiples and international benchmarks.

Corporate finance and advisory, retail brokerage and investments and institutional asset management are other areas where the new law provides a lot of potential. Riyad Bank chief executive Talal Al-Qudaibi says that he believes the CML provides an important vehicle but “will require different strategies for different market segments”.

Banks may look for different international partners in various areas and some banks will only focus on select areas. Arab National Bank chief executive Nemeh Sabbagh says that his bank will concentrate on the distribution side and avoid the advisory-related business. “Not everything is for us.”

Listing opportunity

Abdullah Sulaiman Al Rajhi, chief executive of Al Rajhi Banking & Investment Corporation, believes the new law will be an opportunity for new companies to be listed and participate in more products – not only equities but bonds and debt-related products. Mr Al-Rajhi is also likely to be active in mergers and acquisitions but will shun external arrangements and build in-house capability.

Bank Saudi Fransi (BSF) takes a less sanguine view of the new law. Mohamed Ghanameh, head of corporate banking at BSF, believes that there is no strong requirement for what the new lawprovides and doubts there is a demand for debt/equity issuance. “There is no sense of urgency for the CML. Implementation still needs to take place and that will take some time. We see raising funds through IPOs as still some time down the line,” he says.

The rather gloomy BSF view of the impact of the law appears to be a minority opinion. While HSBC’s Mr Gray says that it may take two years to get what is, in effect, a new investment banking market fully operational, he is extremely bullish about the overall end results and others also expect a quicker response. Dr Fahad Almubarak, president of Riyadh-based Malaz Financial Advisory, says: “This law will hit the ground running, the market will take off within the next 12 months and we will see more companies going public around that time.”

Mr Almubarak is confident about the overall project but is concerned about aspects of the implementation. “We hope that the government will offer the new commission [Saudi Arabian Securities and Exchange Commission], the financial and human resources required to achieve its mission as well as SAMA has been doing.

“I also hope that the new commission will be careful in scrutinising new offerings so we do not get hit with failed IPOs that will damage the credibility of the new process,” he says.

Dr Abdulaziz Al-Dukheil, president of the Riyadh-based Consulting Centre for Finance and Investment (CCFI), also expresses concerns. He gives credit to SAMA but says: “What has been proposed is good and long overdue. The framework is good and there are excellent reasons to be hopeful but there is still a lot to be done. Having the right framework is not enough; it depends on what happens next on the operational side.”

True test of CML

In the months ahead after the appointments to the commission are made, the true test of the CML will come. But for Bahrain and Dubai, the real worries already exist. If 75% of the business in Bahrain and Dubai is directed at the kingdom, as one international banker notes, then there will be growing pressure to shift operations to Saudi Arabia if it has the right legal infrastructure in place.

While Bahrain and Dubai may offer more agreeable venues, especially for foreigners, the advantages of doing business in Saudi Arabia out of these neighbouring countries may become less obvious if the Saudi financial infrastructure improves.

Also, in a new regulated Saudi environment the ability of the ‘briefcase bankers’ to operate as they did changes considerably. Swanning in from Bahrain and Dubai (or elsewhere) will not be the same in a licensed, regulated market. The game is about to change significantly and it is possible that Bahrain’s offshore banking industry and the newly-created Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) may be seriouslydamaged.

Dominant market

The World Bank estimated a few years ago that private wealth in Saudi Arabia was in excess of $500bn. However conservative that figure may be and however much it has grown since, the kingdom is the dominant market in the region by a long margin, and if the new law allows more business to be done directly in the kingdom then some activities are likely to gravitate there. Optimists can also argue that a more efficient, better regulated Saudi market will provide greater opportunities for all, including Bahrain and Dubai.

Although it is not clear how and when the new law will be implemented, it seems to have been well received by the financial community and it should in time transform the financial sector and the economy.

If this law can free up the private sector, as expected, it can add 1%-2% to GDP growth and provide desperately needed jobs, according to experts. In a country where 70% of the population is under 22 years of age and youth unemployment is high, creating jobs is a political imperative. There is a desperate need for the new law to work effectively.