What’s happening?

In January 2015, the rapporteur to the European Parliament on bank structural reform, Gunnar Hokmark, submitted his draft report. This is his reinterpretation of a legislative proposal by the outgoing European commissioner Michel Barnier a year earlier. Mr Barnier’s draft was itself based on a 2012 report by the EU’s expert group chaired by Finland’s central bank governor Erkki Liikanen.

The Liikanen group recommended separating the trading desks of universal banks away from core operations such as retail and corporate banking and payments. Mr Barnier suggested criteria for systemic banks that should receive this treatment, including their proportion of trading assets to total assets. But he proposed that splitting banks up should be a last resort if they could not demonstrate resolvability. Instead, he wanted to introduce a ban on certain activities considered proprietary trading.

Mr Hokmark now proposes diluting the concept further. Market-making activities would be excluded from the trading desk separation under all circumstances. In addition, the metric for selecting banks would be based on their proportion of market risk-weighted assets, rather than just the gross unweighted figures for the trading books. This would allow banks to benefit from netting, hedging and assets deemed low risk in calculating whether they cross the threshold.

A new tone?

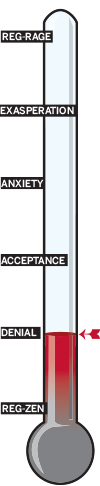

The rapporteur has chosen to change the focus of the structural reform debate away from financial stability, which was the original remit of the Liikanen group. Mr Hokmark, a member of the largest parliamentary grouping, the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP), says that his first concern was to support the EU growth agenda set out by Jean-Claude Juncker, the new European Commission president and the EPP’s candidate for that role.

“We cannot proceed with a discussion about regulation of our main financial institutions without considering what sort of effects it will have on the European economy,” says Mr Hokmark.

He linked the exclusion of market-making activities specifically to Mr Juncker’s plans for a capital markets union, unveiled on February 18. Mr Hokmark says there is an investment gap of about €400bn to €700bn in the EU. The separation of banks’ market-making risks 'breaking the chain' that links the real economy with access to capital market financing.

Why the fuss?

Centre-left and left-wing parties in the European Parliament are voicing the suspicion that capital markets union is an excuse for Mr Juncker’s EPP colleagues to begin pushing back on financial regulation, in a way that was not politically possible in the years after the financial crisis. Brian Hayes, another EPP member active in the parliament’s economic and monetary affairs committee, hinted at this during a discussion on capital markets union at the party’s think-tank, the Wilfried Martens Centre, in February 2015.

This has triggered a tough response to Mr Hokmark’s draft. Jakob von Weizsacker, shadow rapporteur for the Social Democrat Party (the second largest in the parliament), warns that his group is still “far apart” from Mr Hokmark.

“Some people are suggesting that we should essentially stop regulating the banking sector and focus on growth. I would argue that it is surely better for growth and for the efficient allocation of capital if we stop the implicit subsidies going to too-big-to-fail institutions,” says Mr Weizsacker.

What’s the alternative?

Mr Hokmark suggests that the “alphabet soup” of other directives passed since the Liikanen report, on deposit guarantee schemes and bank resolution and recovery (BRRD), have made it easier to tackle failing banks without a government bail-out. But Mr Barnier’s successor as European commissioner for financial services, Jonathan Hill, is less convinced.

“BRRD was an important step forward, but the issue is that some banks remain so complex that questions have to be asked about resolvability and about the concentration of risk. We are looking at a number of proposals coming from both the European Parliament and the Latvian presidency [of the EU Council], and we are keen to work with them to find an outcome that is proportionate and pragmatic, while also addressing the risks. It is clear those discussions have some way to run,” says Mr Hill.

One European regulator involved in bank resolution says the feeling in the European Commission is that the final structural reform legislation will need to demonstrate “clear value-added” beyond BRRD. To some extent, that will depend on how demanding bank resolution plans need to be to comply with BRRD. The US authorities have rejected all the first-draft resolution plans of the country’s largest banks as unworkable.

“European national resolution authorities are actively discussing the question of resolution plans. The primary goal is to achieve a consistent application of the single rulebook. How high the bar will be set in terms of what those plans need to deliver is still being debated,” says the regulator.