Bankers in New York and London who feel over-regulated, overtaxed and generally unwanted will probably not be considering relocating to Vienna. The Austrian government is also engaged in a series of measures that are detrimental to banks, including special bank taxes and an Austrian finish to the regulations that propose to have banks fully Basel III-compliant by 2013 as well as a SIFI (systemically important financial institution) capital surcharge of up to 3%.

On top of this, the government is earning an 8% return on the participation capital it put into leading banks at the time of the crisis, even though it is questionable as to whether it was really needed in all cases.

With a leading bank such as Raiffeisen Bank International (RBI), the combination of €140m coupon payments on its €1.75bn participation capital plus €100m in Austrian bank taxes is taking some 20% out of its profits – on top of the 25% standard Austrian taxes that it already pays. If other bank taxes from the central and eastern European countries are also added in (from Hungary, Slovakia and Poland), then RBI will be looking at a €190m bill in 2012.

Political gains

“You see how strong this institution has to be to carry all this burden and still to show €1bn in profits,” says RBI’s chief executive Herbert Stepic. He adds that although there is an argument that the banking industry should pay for the Austrian banks bailed out by the tax-payer – Kommunalkredit Austria, Hypo Alpe Adria and OeVAG (Oesterreichische Volksbanken) – the taxing of banks has now taken on a political dimension that runs contrary to the desire to have banks finance a strong economic recovery.

“I told the finance minister at the time [Joseph Pröll, who was succeeded by Maria Fekter in 2011] that this [imposing of special taxes] is most probably the worst decision [the government] can take for the future of the banking industry, which has to play the vital role of financing the upswing after the crisis. If you weaken the institutions that have done well [coming through the crisis], you are killing your own milk cow, and you are risking – by giving that example – that all the other countries will do the same, and this is exactly what has happened.”

If you weaken the institutions that have done well [coming through the crisis], you are killing your own milk cow

Mr Stepic complains that countries where there was not a banking crisis, such as Poland and Slovakia, are now imposing special taxes on banks. He also says that he now has doubts about whether taking the participation capital was the right decision as RBI was not short of capital at the time.

“At the time when we took the participation capital, we did not take it because we needed capital... and I am asking myself if I would do it again. The reason was a totally different one. We discussed the issue with the finance minister and the chancellor and we felt we needed to give a sign of confidence to a very disturbed retail market [deposit guarantees were also increased].

“Now, of course, the equation has changed, the regulator has asked us to double our capital and there is a need for this capital.”

Regulatory concerns

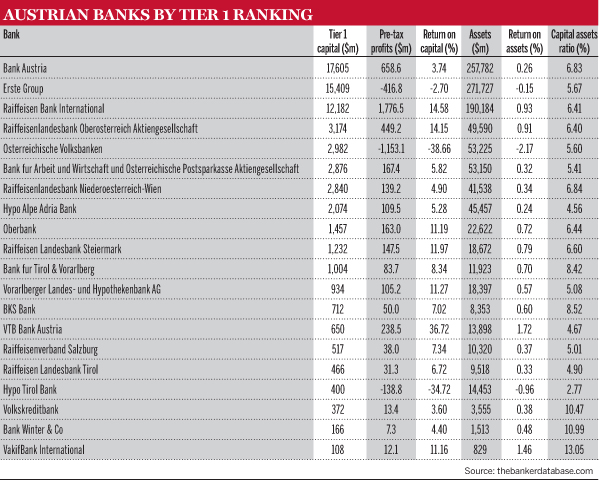

Other Austrian bankers are also concerned about the taxes and regulations they face. Bank Austria’s CEO, Willibald Cernko, says: “There is a certain risk that the system gets overloaded [with taxes and levies]. Over the past six years, the average net profit of the Austrian banking sector is €5.5bn. If we consider all the elements, such as the bank levies, [proposed] financial transactions tax and regulatory burdens, we are talking about a bill of €5bn to €8bn [annually]. In relation to Austrian banking profits this could be an unbearable burden.” Bank Austria, which is owned by Italy’s UniCredit, paid €58.7m in bank levies in the first half of 2012 while reporting a net profit of €646m.

Mr Cernko feels that Austria is overbanked and in need of consolidation, although he says that Bank Austria will not be a player in this process (executives from RBI and Erste also said the same).

“Austria has been described by a former finance minister as overbanked and overbranched and we need further consolidation," says Mr Cernko. "UniCredit Bank Austria is the result of a very significant consolidation process over the past 10 to 15 years and a very successful one, having come through the crisis in profit and without any government support. Over the past 12 years, we have reduced our branch network by 40% and we are looking at ways of using modern media to better serve our customers.

“Looking at further consolidation, we expect there to be developments involving Kommunalkredit, Hypo Alpe Adria and OeVAG. Bank Austria will not be involved but it is very likely there will be a bad bank created for bad assets and some kind of workout. There could also be consolidation between the rural-based co-operative banks and Vienna-based Bawag. The worst outcome would be if things were kept alive with huge government support and so distort the entire market.”

Participation capital

Bank Austria did not take participation capital but – in addition to RBI – Erste, Bawag and Hypo Alpe Adria all received some. OeVAG received its third bailout earlier this year with an injection of €250m, giving the state a stake of 49%. Austrian chancellor Werner Faymann said at the time: “The tax-payer will not pay for this crisis. This will be financed by the banking sector through measures relating to the owners.” The bank tax was raised 25% to help achieve this.

Ratings agencies such as Standard & Poor's have already downgraded Austria due to its banking problems, and there are threats to take further action if the situation deteriorates.

For Erste Bank’s deputy CEO, Franz Hochstrasser, one of the biggest problems of the participation capital is that where it has been privately raised it does not count as core Tier 1 capital under European Banking Authority (EBA) rules, although it does count under Basel III. Erste has €1.2bn of state-originating participation capital and €500m from private investors.

The problem [in terms of growing the bank] is not the capital requirements but that the demand for credit is very limited. As long as the crisis persists, the appetite for investment and for new loans is limited

“I am not so concerned about the cost of the capital [8% coupon] but I would like to have the state out of the company,” says Mr Hochstrasser. “If I could replace it with another financial instrument that also paid 8%, I would do it immediately. The problem is that it would not count as core Tier 1 under EBA rules.”

Mr Hochstrasser is more relaxed about the Austrian finish than some of his competitors. “These regulations have not been settled yet. They are still being negotiated but I think Erste has sufficient equity to meet any of the requirements. The problem [in terms of growing the bank] is not the capital requirements but that the demand for credit is very limited. As long as the crisis persists, the appetite for investment and for new loans is limited.”

Eastern Europe effect

Erste Bank came through the worst of the crisis well and continued to report profits between 2007 and 2010. But then in the third quarter of 2011 it was badly hit by the results in its underperforming Hungarian and Romanian operations and recorded a net loss of €719m for the year. In first half of 2012 it reported a net profit of €453.6m. The bank has drastically reduced its money market funding from €40bn before the crisis to €20bn today and at the same time has increased its European Central Bank eligible collateral from €20bn to €30bn – this means it can survive a money market shutdown.

Despite the severe problems particularly in eastern European countries, Mr Hochstrasser is confident that growth patterns in the region will be better than in the eurozone. The three major Austrian banks – RBI, Erste and Bank Austria – all have extensive eastern European operations and earn more than half their revenues from the region. In RBI’s case, the figure is more than 80%, but this is because under the bank’s new structure, Austrian retail sits elsewhere. The result has been high non-performing loan (NPL) ratios in troubled markets – for Erste 26.2% in Romania and 24.6% in Hungary with an across-the-board coverage ratio of 61.2%. RBI’s overall NPL ratio is just under 9%, with 68% coverage.

Mr Stepic is also positive about the region’s ability to recover fast, saying that economies there respond much faster to austerity programmes than in the the less flexible economies of western Europe. “Central and eastern Europe has been doing much better than was expected. Politicians there reacted fast to the crisis, and austerity programmes in ex-communist countries are much easier to implement than in western Europe. They have been doing very well in bringing down current account deficits and in solving their refinancing needs, and have more or less completed this for 2012,” he says.

Bank Austria’s Mr Cernko says: “In our current approach to eastern Europe, we are very much focused on those countries where we see sustainable growth opportunities. We are very confident when it comes to Russia, where we are mainly focused on the large corporates. We are very happy with our performance in Turkey but we are also happy with countries such as the Czech Republic, even though it faces a recession, but the overall shape of the country is pretty good and our market position is excellent.”

This exposure to markets with fast growth potential is obviously an advantage for Austria, but for all this the country is still impacted by the eurozone crisis and the difficulties of some of its banks.

Fitch even talked in a report at the end of last year about a decoupling of Austria from the stronger eurozone players, such as Germany, the Netherlands and Finland. Erste’s Mr Hochstrasser rejects this idea. He says: “Economic development in Germany and Austria has been fairly similar, with 50 years of very little currency volatility [prior to joining the euro] and both economies being efficiently run and highly export-oriented. I do not expect a decoupling of Austria from the German bloc, rather I expect a further widening between the German bloc and the southern countries.”

Domestic landscape

All the leading Austrian bankers agree that the country's domestic banking situation would be helped with further consolidation. The problem, however, is to find buyers for troubled and recovered assets. “There will be very few buyers and there will be wind-downs. We don’t want to buy more assets. If I want to produce more assets I can do it with [RBI's] existing structure. Why should I burden my profit-and-loss account by taking over assets that are not producing profits?” says Mr Stepic.

One bank executive whose challenge will be to find buyers in a difficult market is Gottwald Kranebitter, the CEO of Hypo Alpe Adria. The bank has expanded rapidly into the Balkans during the past decade using wholesale funding, but without proper risk management. It ran into trouble and was nationalised in December 2009. A new management team led by Mr Kranebitter was installed and is attempting to restore it to health. In first half 2012, the bank lost €9.9m compared with a profit of €71.8m in the first half of 2011.

The Hypo story is a colourful one. The bank is based in Klagenfurt, capital of the Carinthia region of Austria, which due to its location looks more to Italy and the Balkans for its direction than to Vienna. The region was governed by far-right populist politician Jörg Haider from 1989 to 1991 and again from 1999 to his death in a car crash in 2008. His BZO party still holds power in Carinthia. There were strong connections between Mr Haider and Hypo and he is believed to have opened doors for the bank in Croatia. It was in difficulties when it was taken over by Bayern LB in 2007, but the German bank was unable to prevent its subsequent nationalisation.

The new management team has undertaken a top-to-bottom analysis of the bank’s assets, put in place comprehensive risk management and divided the bank into three saleable parts – Austria, Italy and south-east Europe – as well as selected assets to wind down.

In its first half of 2012, the bank reported that it had further reduced total assets by €1.4bn to about €33.7bn and strengthened equity following hybrid repurchases. “Our aim is to prove that the three banks we have identified for sale are in a viable condition so that we can find buyers,” says Mr Kranebitter.

Investment banks have been hired for the sales process and the European Commission is set to impose a timetable at the end of 2012 or early 2013. “We have started the sales process for the three viable parts by hiring investment banks, but for the wind-down assets we will be doing it ourselves to save taxpayers’ money,” says Mr Kranebitter. The problem will be finding buyers. “The market for banks is dry, and for south-east Europe banks even drier,” he adds.