The threat of state-owned bank collapses suggests that Germany may have suffered more than most European countries from the avalanche of consequences triggered by the US subprime crisis. Beyond the state sector, however, leading German banks are noticeably calm about the prospects for 2008.

The German economy is already slowing, but Jörg Krämer, chief economist at Commerzbank in Frankfurt, points out that domestic companies are in relatively good health. “Manufacturing no longer plays a role in the British economy,” he says, only partly in jest. “But in Germany, it is the growth engine,” and one that has significantly outperformed the European average for the sector in recent years. “The profit situation of German firms has been so good that the non-bank sector made nearly no additional borrowing from the banks in 2007, the growth rate in corporate lending was close to zero.”

Competitive edge

In the context of a credit crunch, this should be a source of strength, says Mr Krämer. Internally generated funds are high enough to cover capital expenditures, allowing German firms to grow organically even if new financing is scarce. Inevitably, the manufacturing sector’s orientation toward exports means that it will not escape the effects of a global slowdown. Yet remarkable wage restraint has given Germany a competitive edge over other European economies in terms of unit labour costs, says Mr Krämer. These have fallen by about 10% since the adoption of the euro in 1999, while the eurozone average has remained constant – or risen if Germany itself is excluded from the reckoning.

Strong balance sheets may help German issuers to navigate the repricing of risk, but the higher cost of borrowing is still a shock for most company treasurers, says Roman Schmidt, global head of corporate finance at Commerzbank in Frankfurt. “There is not much testing of the water, and there are not many fish in the water.” He acknowledges that the investor appetite for asset-backed securities and high yield corporate paper is likely to remain subdued for some time. However, he argues that investors are still looking for new paper to buy, and finding it in short supply because of issuer reluctance to come to market.

Consequently, Mr Schmidt expects a decent response to deals at the right price, especially from good-quality corporate issuers. “It is a bit of an excuse for issuers to say the market is not there. In reality, it means they don’t want to pay the current spread,” he says. He expects that attitude to soften if the tougher conditions persist and is warning clients not to expect a rapid return to the luxury of very tight pricing that prevailed before mid-2007. Still, he recognises the difficulty for treasurers to explain to their boards why they should pay up to borrow today and risk embarrassment if the market improves tomorrow. “Nobody wants the ‘lemon of the year award’ for being the ones who paid the most.”

Given this caution, Mr Schmidt believes that equity offers a more flexible means of raising capital in the current climate, because issuers can start with a small initial listing and then float more of the company when markets pick up. This has encouraged Commerzbank to make a strategic switch. Since about 2003, the bank has focused on debt capital markets activity, moving into the top three in terms of deal volume in Germany, from outside the top 10 previously. Last year, Mr Schmidt’s team took the decision to renew their attention to equity markets.

In addition to the credit crunch, there were positive reasons for this plan. “In the next two to three years, we are going to have an interesting mixture of new industries needing equity capital, including the life sciences sector, which is still extremely fragmented in Germany, and renewable energy. These are also two sectors where Commerzbank is prominent,” says Mr Schmidt.

Locusts no more

Mr Schmidt adds one other reason why he is stepping up the bank’s equity market capabilities: the potential to become involved in fresh corporate debt restructuring activity if financial conditions continue to deteriorate. “If there should be any increase in the next few years, it will probably involve more investment bank-style restructurings than ever before, using equity cures that require expertise in this area,” he says.

If there is a new wave of restructurings, it will test public attitudes to the financial sector and especially to the role of alternative investors, such as hedge funds and private equity – which were condemned as “locusts” by labour minister Franz Münterfering in 2004.

From her panoramic viewpoint on the 38th floor of Frankfurt’s Skyper tower, Britta Grauke, a partner at law firm Weil, Gotshal & Manges, believes that she can perceive a more accommodating climate evolving. “Since the locust discussion, attitudes have changed, and we have been involved in restructurings… where we found that there was a very good discussion between companies and creditors, including foreign funds. The companies understood that this was a chance rather than a threat.”

In particular, Ms Grauke experienced this new approach when she advised UK-based private equity fund Kingsbridge on the purchase of German model train manufacturer Märklin in 2006. The Märklin workers’ council was apparently supportive of a private equity investment to revitalise the distressed firm’s fortunes.

Legal constraints

However, the strict German legal context still constrains the debt restructuring process. Significantly, Ms Grauke moved into corporate restructuring work from the litigation side, where she had encountered the effects of Germany’s tough manager and creditor liability laws. These require that companies must restructure or enter receivership within just three weeks of identifying a cash-flow crisis. Moreover, the receiver is appointed by the court, which limits creditors to suggesting their preferred candidate, and offers little potential for out-of-court restructurings.

In the past, this has encouraged jurisdiction-hopping – the use of foreign holding companies or debt listings to move the company’s registered ‘centre of main interest’ out of Germany. The most notable example was the debt write-off and debt-for-equity swap carried out in the UK by German vehicle parts manufacturer Schefenacker in 2006.

Ms Grauke warns that this approach does not make sense for every company. “It may trigger substantial tax issues or issues with employees that mean it is not easy to shift your centre of main interest,” she says. Still, she believes that Germany is some distance behind the UK in its thinking on ways to facilitate out-of-court restructuring as a means to protect jobs. “We are just beginning that discussion here.”

Another growing trend has been the sale of non-performing loan (NPL) portfolios, with Lone Star Germany, the most high-profile player. But Mr Schmidt emphasises that sales of NPLs at heavily written-down values to foreign buyers, in the style of Japan or South Korea during the 1990s, are unlikely in Germany. “All of the banks have their own intensive treatment departments which look to help companies. We have work-out experience going back more than 120 years. And last year, Germany had one of the lowest credit write-off rates ever,” he says.

In addition, the most cash-strapped banks – those in the state sector – are likely to pull back from some of their investment banking activities and focus on relationship lending. This means preserving their corporate loan portfolios.

State bank dilemma

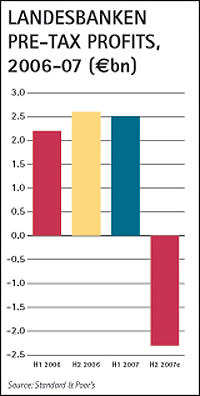

Their domestic loan books may be sacrosanct, but the fate of the Landesbanken is increasingly uncertain, after several were revealed as unlikely victims of the subprime crisis. Sachsen LB and IKB Deutsche Industriebank were names more associated with cautious small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) relationship lending than illiquid US mortgage-backed securities, but both were laid low by the conduits and SIV-lites (structured investment vehicles) they had set up to invest in this asset class. SachsenLB was bought for just €328m by Landesbank Baden-Württemberg (LBBW) in a deal completed on January 1, and only after conduits worth €17.5bn were taken off-balance-sheet and guaranteed to the tune of €2.75bn by the Free State of Saxony regional government.

IKB has needed multiple bail-outs, most recently in February. At this point, the largest state-owned lender of all, KfW, which had led the earlier rescue efforts, warned that its €4.95bn general contingency fund was drying up, obliging the federal government to bridge the gap. KfW now owns 38% of IKB, together with a convertible bond that could increase that stake to more than 43%. The policy lender is committed to selling this stake, and has hired Merrill Lynch and Kvarnström as its advisers.

Horst Seissinger, head of capital markets at KfW, acknowledges that investors have raised questions about the role that KfW is playing in the IKB situation, and is quick to reassure. “KfW’s support measures for IKB do not have any impact on KfW’s funding strategy,” he tells The Banker. KfW’s funding needs are projected to increase by just over €5bn this year, to €70bn, but this is mainly attributable to the strong growth of the bank’s SME lending promotions, says Mr Seissinger.

Risk shield

Adding to the list of interventions by the federal and regional governments, WestLB announced what it called a “risk shield” scheme in February to ring-fence about €23bn in at-risk structured finance investments into a special purpose vehicle. The financing for this will include a €5bn guarantee from the bank’s owners, with a disproportionate burden falling on the State of North-Rhine Westphalia (NRW).

Taken together, these public-private rescue efforts are creating legal innovations, says Gerhard Schmidt, the managing partner of Weil, Gotshal & Manges’ Germany practice. “You have complex deal structures, an overlap of securities laws, public shareholders and different risk layers that will be treated differently. KfW has taken on some of the risks for IKB even while IKB is still a listed company.” Mr Schmidt is familiar with such new territory, having acted for the institutional investor consortium organised by private equity firm JC Flowers that purchased 26.6% of HSH Nordbank in 2006. That was the first foreign strategic stake in a state-owned German bank.

However, Mr Schmidt emphasises the difficulty of generalising about whether these developments will lead to greater private involvement in the sector. “The obstacles are not insurmountable but when you look at the landscape, there are different signals coming from different banks.” He believes that the authorities in Düsseldorf are increasingly open to the idea of private investment in WestLB, after strong signals from NRW prime minister Jürgen Rüttgers.

Europe’s watchful eye

Key decisions may be taken beyond Germany. The European Commission has already announced a full review of the IKB and SachsenLB bail-outs, and Gerhard Schmidt expects that this will extend to include WestLB’s risk shield. A spokesman for EU competition commissioner Neelie Kroes confirmed to The Banker that the department was already in close contact with the German authorities about the WestLB proposal. “The commission is awaiting notification. Once we receive it, we will study it carefully,” says the spokesman.

Stefan Best, director of German financial institutions credit ratings at Standard & Poor’s in Frankfurt, doubts that the commission would want to run the risk of a bank failure by rejecting the restructuring plan outright, but warns that there may be stringent conditions attached to its approval. “If the commission comes to the opinion that the restructuring aid is a distortion to competition, there must be compensation. This is typically in the form of shrinking – selling business, selling assets.”

Such conditions will add to the momentum for consolidation in the state-owned sector, which Mr Best has been anticipating ever since the commission ordered the abolition of state guarantees for Landesbank borrowings in July 2001. That removed the competitive advantage for the wholesale lending institutions, and private banks, especially Commerzbank, are eating into their market share in SME lending.

The integration route

To date, the Sparkassen (savings banks) that hold stakes in Landesbank Hessen-Thüringen Girozentrale (Helaba) have given a cool response to WestLB’s proposal that the two Landesbanks should merge.

However, Mr Best believes that greater integration with the Sparkassen remains essential for the Landesbanken and savings banks. Not only would the savings bank deposits offer a cheaper source of funding for wholesale activities but, he says, Landesbanken and Sparkassen can co-operate better through cross-selling to the savings banks’ existing customer base and winning new clients. “[Landesbanken] could gain new mid-sized corporate customers with the help of savings banks that maybe do not have a main banking relationship with such companies but have access to them through their wide distribution network and savings schemes for the staff; or they could co-operate where savings banks lack the products needed to serve their existing customers.” This is also the case in banking with affluent and private banking clients, where savings banks do not have a strong reputation.

For anyone expecting 2008 to be a year of dramatic change, however, one senior banker now in the private sector offers a cautionary tale. Early in his career, he provoked the scorn of a neighbour by announcing that he was joining WestLB. “He said, all these Landesbanken are going to merge, there is no future in this bank.” That was in 1982.