For a mortgage bank to pull back on mortgage lending in the midst of a housing boom is indeed a radical decision and not one to find favour with the majority of bank equity analysts. But that is what the boss of the UK's Abbey bank - part of Spain's Santander group - did as his first major decision within three months of taking on the role of CEO.

With a 20% price correction coming in the UK's overheated property market about 18 months down the line, it turned out to be one of the most significant decisions António Horta-Osório has made in a 20-year career.

"It was a very tough decision and there was a great debate within the bank," says Mr Horta-Osório of the strategy he implemented in September 2006. "It is much easier to be wrong together than to be right alone [all other UK banks were growing their mortgage books].

"It was not obvious [that it was the right decision] and many analysts were rewarding our competitors when they were increasing market share at zero spreads. They said 'Abbey is not doing so well, the activity is going down'. They had doubts as to whether we were doing this as part of a [well-thought-out] strategy or whether it was because we didn't know what we were doing." He concedes that if Abbey has been separately listed in the UK, the decision would have been even more difficult as the share price would have taken a pummelling.

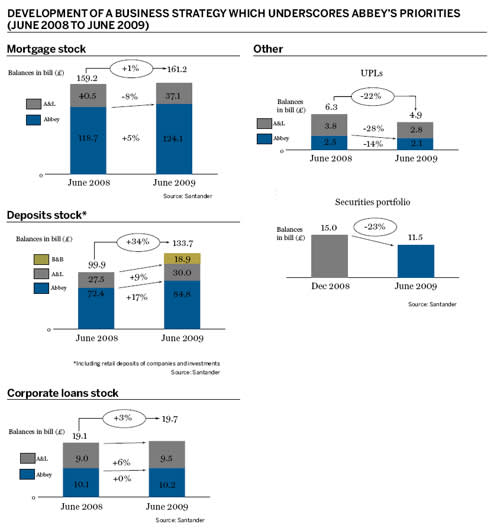

With the luxury of hindsight, it is obvious that decision to cut back Abbey's share of the UK mortgage market from 10% to 6%, to shrink consumer lending and to increase the deposit base, at a time when the fashion was for capital markets funding, set Abbey on a course to not only survive the financial crisis but to actually thrive and profit from the fallout.

Big acquisitions

Two UK banks that got into difficulties - Alliance & Leicester (A&L) and Bradford & Bingley (B&B) - fell into Abbey's hands. This enabled Santander to double the size of its UK retail operation at a cost of about half of what it had originally paid for Abbey. In the case of B&B, the bank only took on the deposits and the branches, leaving a troublesome buy-to-let mortgage portfolio with the UK Treasury.

With competitors facing the challenges wrought by lending too much in the preceding boom, Abbey has been able to come back strongly in mortgages at spreads of 2% (compared with 15 basis points [bps] to 20bps in 2006) and to recover and improve upon its original 10% share of the UK mortgage market. Moreover, while property prices have fallen 20%, Abbey's average loan to value has only increased by between five and six percentage points to 51%, with only 9% of mortgages at loan to values in excess of 100%.

Santander's UK profits were 33.1% up in the first half of 2009 when compared with the first half of 2008, if the acquisitions are excluded, and 62.8% higher if both the acquisitions and the decline in sterling relative to the euro are taken into account, according to figures in a report by debt analysts Creditsights. The investment bank Keefe, Bruyette & Woods described it as "a great performance in a tough market". Other UK banks, if they are making profits at all, are mostly earning them from the bounce back in capital markets rather than from the retail side.

"What we had last year was quite a rare set of circumstances. Given that we had previously restrained our market share [in mortgages], we had kept our risk standards neutral and enhanced our deposits, we were in a very strong position in relation to the market in terms of being able to lend with prudent risk criteria, with attractive margins and using internal funding," says Mr Horta-Osório.

"Last year, we got a more than 30% share of net lending with not only higher margins which went from 20bps to more than 2%, [as well as this] 90% of our approvals had loan-to-value ratios of 75% or below. It is an extraordinary set of circumstances where you can increase your market share at better margins and at better risk criteria."

Mr Horta-Osório acknowledges that there was a significant impact from the running down of failed UK bank Northern Rock's mortgage portfolio, which is now in government hands. There was also a lot of remortgaging and Abbey was able to offer attractive rates to customers with significant equity in their homes.

But this does not detract from the significance of Abbey's change of direction in 2006 when an alternative response to declining spreads, adopted by some competitors, was to move into higher yielding buy-to-let, self-certified and subprime mortgages.

Mortgage roots

Abbey's origins are as a UK building society which demutualised in 1989, but continued to focus on the retail side in plain vanilla mortgages and savings. Ingrained in its DNA was the need to grow in mortgages and preserve its share whatever the condition of the market. This ran counter to what Mr Horta-Osório describes as Santander's DNA of prudence in risk taking yet being commercially aggressive and innovative.

"We have a total separation between the risk and the commercial function because we believe people cannot act in two different capacities. We studied the risk-adjusted alternatives of buy-to-let, of self-certification and of subprime and we considered that those were areas where we should not have a strong focus. We have less than 3% of our mortgage book in buy-to-lets so 97% of our book is prime residential mortgages."

In some ways, Abbey came into Santander's hands because of its own failed attempts to find an alternative to standard mortgages and savings. The bank's treasury embarked on an ill-fated strategy of investing in high-yield bonds which led to a restructuring, a sale or rundown of £60bn ($99bn) of assets and its eventual sale to Santander for £9bn in 2004. The Spanish bank had an advantage in the acquisition process as the sale of Abbey to any of the major UK players was unlikely to gain approval on competition grounds. A bid by UK bank Lloyds was blocked in 2001. In hindsight, it was one of the better decisions that the UK authorities made as the alternative of selling to a UK owner might have been another bank sitting in the government's casualty ward - although at the time, that was not part of its thinking.

When Santander took over in 2004, Abbey delisted from the London Stock Exchange and there was a fuss in the UK national press as its thousands of small stakeholders - who obtained their shares at the time of demutualisation - contemplated life as owners of Madrid-listed Santander with stock priced in euros.

Mr Horta-Osório, who had previously spent seven years as CEO of Santander Totta in Portugal, arrived at Abbey in July 2006, a month before his official appointment was due to take effect, to get an early handle on the situation before he needed to take any decisions. Already a non-executive director, he knew something of the challenges facing the bank and that substantial measures would be needed.

"What struck me the most was that the margins we were getting both in mortgages and in consumer lending were trending towards zero. With mortgages they were 15bps to 20bps and when you take into account the cost [of running the bank] they were very close to zero which was obviously unsustainable," he says.

"In consumer lending, it was a strain as well because the margins were about 3% - in what was a very good economic moment - and were only equal to the provisions you had to make. It was a loss-making business. At the same time, I noticed that Abbey was flat in deposits and so it was losing share in deposits [as the market was growing]. At that time, funding was easy and was not considered a priority."

Mr Horta-Osório says that it was quite difficult to win his argument internally that the bank should pull back from the mortgage market, but he had the support of the Santander group and it was also part of a coherent strategy to turn Abbey into a full commercial bank with small and medium-sized enterprises and corporate lending, treasury services, credit cards, mutual funds and insurance products.

By October, Abbey was telling the press that it would be balancing value and growth in the mortgage market. Logically, from a profit and loss standpoint, the bank could have quit the mortgage market altogether, but Mr Horta-Osório says that with Abbey's background in mortgages and the relationship it had formed with the majority of customers, he favoured an approach in the middle ground.

Consumer lending is less visible and the task there was easier. By the end of 2006, total lending was already 20% down and has since been reduced by 50%. "In terms of UPLs [unsecured personal loans], we could not increase the margins because in UPLs if you go significantly apart from the market average, you have a moral hazard problem. You get the bad clients and by more than you charge, you will get a negative impact. Today, for example, the margin of the [UK consumer lending] sector is 9% and the credit loss is about 8%," he says.

Far-reaching plans

The other key parts of Mr Horta-Osório's strategy for Abbey and its acquisitions - which together account for about 20% of group earnings and will rebrand under the Santander name next year - are the expansion of the deposit base, the moving of all operations onto Santander's Partenon IT platform and the reduction of the cost-income ratio. The aim is to create a virtuous circle whereby the reduction in costs allows the bank to pass more value to customers so that total revenues go up and the cost-income ratio becomes even more attractive.

The 2006 decision to grow deposits was taken without any inkling that capital markets were destined to seize up and create critical funding problems for some banks. Deposits at the time were flat and the sales force was rewarded for acquiring new deposits rather than on the net position. This has now been changed and Creditsights reports that deposits have increased 17% above the June 2008 level and risen 85% if A&L and B&B are included. As B&B came without assets, the combined acquisition was self-funding and gives the bank a loan-to-deposit ratio of 125%, well below the sector average of 145%.

"I have always thought that a bank does not grow by credit," says Mr Horta-Osório. "A bank grows by capital and by deposits and these determine the amount that you can grow the credit.

"Given that Abbey was flat in deposits [in 2006] and growing credit at 10% or more, I wanted the marginal growth of deposits to be at least equal to the marginal growth of assets. I wanted to have an even growth, going forwards, but of course I did not think at the time that the capital markets would shut down." The push for deposits is still on, with Santander UK aiming to put on 1 million new current accounts in 2009.

Network advantages

Key to Santander's philosophy on the value of deposits is that the branch remains a central vehicle for collecting them and maintaining customer relationships. Globally, Santander has more branches than any other bank - 19,000 - and Mr Horta-Osório recalls that when he was CEO of Santander Totta in Portugal, the bank continued opening branches all through the tech boom when competitors were cutting back as they thought they were less essential, with the coming of the internet.

With the acquisitions, Santander UK has put on 600 branches and doubled the network, giving it coverage in central and northern parts of England, where Abbey's penetration has been weakest. Planning laws in the UK are strict and gaining permissions to open bank branches is a slow business, so to achieve this leap in size organically would have been a three- to five-year project. Through A&L, Santander has also got itself a bigger footprint in the corporate market with £20bn of assets.

But branches are expensive, which makes the priority of cutting costs even more difficult to achieve. Nevertheless, the cost-income ratio at Abbey has come down from 70% when it was acquired to 41%, including the acquisitions and compared with a sector average of 55%.

Mr Horta-Osório explains that this was achieved by cutting headquarters and back-office staff, not by cutting the sales force. Efficiencies were gained through the implementation of the IT system, but also by outsourcing processing to Spain, Portugal and Poland. This sets up a virtuous circle whereby the bank can offer best-in-class products and increase income still further without racking up additional costs.

Driven by results

Mr Horta-Osório has spent a good part of his career working and studying overseas. He worked for Goldman Sachs in New York, obtained his Master of Business Administration at Insead in France, he was CEO for Santander in both Brazil and his native Portugal and naturally, given his employers, he has spent a lot of time in Spain. So how does he find the UK culture?

He replies that he finds his UK team impeccable in planning and organisation, but not always so flexible in changing course mid-stream if circumstances require it. He is noted for commenting: "That was a very British meeting," when form seems to triumph over substance and is a firm believer in the '80/20' rule of achieving 80% of aims in 20% of the time.

"It is important to be very focused on results," he says. "We are in a difficult economic environment and [we] had a company that needed turning around. In those circumstances, don't come to me to discuss if the branch should place two advertisements or one; don't come to me to discuss if we need to paint the wall. Let's discuss how to turn around the bank and how to focus on the main priorities."

He says that the Latin culture can be better suited to managing in a crisis and changing direction quickly. As for the concept of 'British' meetings, he says: "When I arrived at Abbey, I would see fantastic presentations and I would ask 'what does that number mean?' and the person would say 'I will come back to you'. I would say 'don't do a perfect presentation if you don't know what you are doing, because next time I will ask the person who did it for you to come here and present it'."

Unfinished business

While Mr Horta-Osório is clearly a candidate for taking the helm of the entire Santander group at some stage - another candidate is the head of Santander in Brazil, Fabio Barbosa - he still has unfinished business in the UK. Apart from the rebranding, there is a commitment to produce £180m of synergies from the A&L and B&B acquisitions over a three-year period (a task which is ahead of schedule, but not complete) and to carry on the transition to a full-service commercial bank. He has also been given a three-year appointment as a non-executive director to the Court of the Bank of England - a body that reviews the bank's objectives and strategy.

This should allow Mr Horta-Osório sufficient time to visit some or all of the 600 new branches that Santander has acquired in towns such as Leicester and Bradford - the former famous for its red cheese, the latter for its hot curries - and to attend more of those very 'British' meetings where rituals and pleasantries takes preference over results and outcomes. He may need to go outside of Abbey for these, however, as everyone there has now inculcated the 80-20 rule and is ready for whatever challenges the post-crisis UK economy throws up.

Development of business strategy which underscores Abbey's priorities