That Switzerland's asset and wealth management sector's home market is failing to rouse itself from its current state of slumber has been a worry for the country's firms for some time. And the plight of the Swiss market received fresh confirmation in June 2012, in a report from private banking and asset management group LGT.

LGT found that, as the euro crisis rolls on and the accompanying uncertainty about the future of the global economy endures, Switzerland's wealthy, "remain highly risk-averse and fearful of inflation, sovereign debt defaults and the unstable financial system". As a result, 58% of wealth management clients in Switzerland have lost their confidence in the country's asset management system and a significant proportion are anxious about inflation, according to the report. Clients have resorted to cash, gold and the domestic market, and are shunning above-average levels of diversification.

It therefore comes as little surprise that analysts are reporting a trend of Swiss wealth management firms increasingly looking towards the emerging markets to make up for uninspiring domestic business prospects.

“What you are seeing now is that when firms sit down and calculate where global wealth is distributed, it is in the SAAAME [South America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East] region. As a wealth manager, you have ultimately got to follow wherever wealth occurs. Now wealth managers are seeking out opportunities in emerging markets; basically where they believe the greatest wealth is,” says Kevin Burrowes, the UK financial services leader at global professional services firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC).

The acquisition trail

The evidence that major Swiss financial firms have indeed sat down and made those calculations is copious. The announcement by Swiss private banking firm Julius Baer in June 2012 that it was in talks to take over Bank of America's Merrill Lynch international wealth management unit, an acquisition worth $2bn, demonstrated the firm's formidable wealth management ambitions in emerging markets. Previous to that, in 2010, the firm also took over ING's private banking assets in Asia and Europe, which came with a $1.9bn price tag.

Credit Suisse is hot on Julius Baer's tail. It too made a bid for the Merrill Lynch unit in May 2012. The home market is proving particularly challenging for Credit Suisse at present, not least because of unresolved tax issues between the firm and the authorities in the EU and the US. Hans-Ulrich Meister, chief executive of private banking at Credit Suisse, recently admitted that these disputes are “making clients insecure and also putting pressure on the share price”.

In a clear sign that the firm is eager to exploit greener, non-Western pastures, it is hiring more relationship managers for its branches in emerging markets, even while it is making significant cutbacks at home.

As a wealth manager, you have ultimately got to follow wherever wealth occurs. Now wealth managers are seeking out opportunities in emerging markets; basically where they believe the greatest wealth is

“Structurally, the industry is experiencing significant changes,” says one Credit Suisse banker. “From a regional perspective, wealth creation continues to shift towards emerging markets, with higher growth rates fuelled by entrepreneurial activity and relatively strong economic development.”

Other Swiss private banks are also hungry for a larger stake in the wealth management sector outside of Western markets. Dutch co-operative giant Rabobank sold its stake in Swiss wealth manager Bank Sarasin to Brazil-based firm Safra in November 2011, for SFr1bn ($1.02bn). Since then, Sarasin has asked Safra for capital to boost its expansion into India, Asia, and the Middle East, as well as to investigate potential opportunities in Latin America. Similarly, private banking group Pictet is showing healthy expansionist urges in emerging markets.

“We have been expanding our Asia-Pacific wealth management significantly in the recent past, adding a number of senior relationship managers in Hong Kong and Singapore. In particular, we have just gained a banking licence in Hong Kong. We are also active and expanding in the Middle East and Latin America,” says Stephen Barber, a group managing director at Pictet.

Nonetheless, some Swiss asset management firms are reluctant to admit that the increased shift of Swiss firms away from the domestic and Western markets towards the developing world is a recent phenomenon catalysed by the financial crisis, favouring a gentler, long-term narrative.

“The domestic Swiss market, while still significant, has been of less relative importance for some years: one reason is the growth of emerging market economies. Pictet has been closely associated with emerging markets for two decades,” says Mr Barber.

New frontiers

In terms of the particular emerging markets that Swiss companies are moving into, Asia-Pacific remains the main target region. “In general, firms are looking eastwards, especially to China, where the opportunities are obviously huge. Countries such as Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore are also promising,” says Mr Burrowes at PwC.

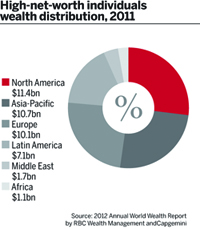

The opportunities that Asia offers for wealth management firms are well noted. According to the 2012 Annual World Wealth Report by RBC Wealth Management and IT consultancy Capgemini, Asia-Pacific is now home to more high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), at 3.37 million, than any other region, including North America, which has 3.35 million, and Europe, which has 3.17 million.

But Asia-Pacific is not the only region Swiss firms are interested in. Latin America also offers promising prospects for the wealth management industry. The region proved resilient during the financial crisis, with the HNWI population decreasing by just 0.7% in 2008 and increasing incrementally ever since. Moreover, Brazil is fast becoming one of the most promising wealth management centres for emerging markets – its HNWI population grew by no less than 6.2% in 2011 to a combined wealth of $951bn, constituting just less than one-third of the country's total wealth.

Although the Arab Spring has raised questions about the future of wealth management in the Middle East, Africa is also starting to put itself on the map. Between 2010 and 2011, the HNWI population grew by 3.9%, making it the region with the second fastest growing HNWI population in the world.

“Africa is a frontier and nascent wealth management market and we expect to see a significant increase in the local presence of wealth management players, including UBS, in various markets across the continent in the upcoming years,” says Paul Raphael, head of global emerging markets at UBS Wealth Management.

But enthusiasm for emerging regions such as Latin America and Africa among Swiss wealth management firms is, at the same time, decidedly more tempered than the commitment to Asia-Pacific. This is because the economic picture is patchier, according to PwC's Mr Burrowes. “For example, Brazil has been experiencing high growth but it has started to splutter. And in Africa, there are challenges over the legal framework and regulation. Also, there are serious corruption issues in some African countries, which makes it difficult to do business in wealth management,” he says.

Unexpected challenges

Overall, Swiss wealth management companies face a number of challenges when it comes to serving markets that differ significantly from those in Switzerland or other European countries. One particularly expensive requirement of operating in Asia serves as an example of this: in certain Asian countries, where seniority is of fundamental importance, there is a particular demand for wealth managers that match their clients in age.

Another more widespread difficulty that Swiss wealth management firms come across is that wealthy clients from certain regions, who may have acquired their wealth against the odds or in the face of formidable challenges, may have more appetite for risk in order to gain higher yields than most Swiss firms would consider prudent.

“In emerging markets, where wealth is concentrated in the first generation of entrepreneurs, rather than 'old money', expectations from a wealth manager can be different – they may have a higher risk appetite. It is our task to encourage clients to think about future generations,” says Mr Barber.

There is also the issue of competition from local wealth management firms, which have a more nuanced understanding of how culture and experience impacts upon the expectations of clients. Itaú Unibanco is a rising star in Brazil, while the Asian market is also saturated with local competitors, including China Merchant Bank and Hang Seng Bank.

But the abundance of local talent for wealth management can be turned into an advantage, according to some Swiss companies, which openly headhunt promising employees from firms in a given country. “Local firms are a serious competition but also the best hunting ground to hire local talent from in order to create our targeted mix between local affinity with international bankers,” says Mr Raphael.

Swiss brand

Swiss firms are responding to competition by placing special emphasis on the Swiss brand, which has powerful international appeal. “In emerging markets generally, the wealth management business is underdeveloped and clients tend to look for outside expertise. I would say that the 'Swiss brand' is definitely a factor; it stands for quality of service, consistency and reliability, security and, we hope, performance, especially in declining markets,” says Mr Barber.

According to Mr Burrowes, the strength of the Swiss brand is useful, but only up to a point. The top HNWI brackets in emerging countries, who are more globally atuned, often prefer to bank with a large, global firm. But the lower segment of wealth management clients in emerging economies will perhaps prefer to bank with a more local brand, he says.

According to some, the fact that Swiss firms' reputation for secrecy is being eroded by European regulatory pressures may compromise their edge in emerging markets. It leaves them on a level playing field with other large international firms that are also pursuing their own strategies to maximise their presence in emerging markets.

“Although the Swiss brand remains strong, there are other very strong international brands looking in the same direction. In that regard, the advantage of the Swiss firm, if it even exists, is very slim,” says Mr Burrowes.

Nonetheless, the outward, expansionist instinct of Swiss wealth management operations should perhaps not be underestimated as an attribute that will leave firms in good stead.

“The Swiss DNA is to venture out to other countries; this is a main growth driver of the Swiss economy in various industries, not only in banking. The Swiss also welcome experts from abroad that complement our skills, approaches and culture. This openness for the unknown and the different is a powerful tool for success in emerging markets,” says Mr Raphael of UBS.