Brexit may not damage London’s position as the pre-eminent financial centre in Europe, but it appears increasingly likely that the UK’s break with the EU will boost other such hubs in the region, from the most established names to the less obvious.

Paris and Frankfurt have long been named in financial companies’ Brexit statements, along with Dublin and Luxembourg. But London-based firms as well as newcomers to the region could miss a trick by overlooking hubs such as Berlin, Barcelona and Milan.

Angry voices

The possibility of a hard Brexit, which would deny the UK access to the European single market, and the UK government’s stated intention to initiate formal divorce proceedings by the end of March, have resulted in an increasingly vocal financial sector.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos in January, UBS chief executive Andrea Orcel said that if no transitional deal was reached between the UK and the EU, jobs will move as soon as the UK government invokes Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which marks the beginning of formal proceedings. He mentioned Frankfurt and Madrid as potential candidates for a number of London roles post-Brexit.

Also at Davos, HSBC chief executive Stuart Gulliver went as far as specifying how much of the trading business would leave its London headquarters: the equivalent of 20% of revenues, the amount that is subject to European legislation. The bank has already mentioned Paris as the possible destination for up to 1000 jobs. One European official told The Banker that continental European lenders, including one in Italy, were seriously considering relocating part of their London-based operations. In 2016, UK wealth manager M&G announced plans to build a Luxembourg platform to serve clients in the single market.

Join the queue

But with opportunity knocking for European financial centres, regulatory issues are arising and office space rent costs are going up. “We have more than 100 hard enquiries for our central bank to establish what the regulatory regime would be in Dublin,” Irish finance minister Michael Noonan told Bloomberg in a recent interview. “Some of the companies have gone so far as enquiring about the possibility of getting their teenage children into good schools in Dublin.”

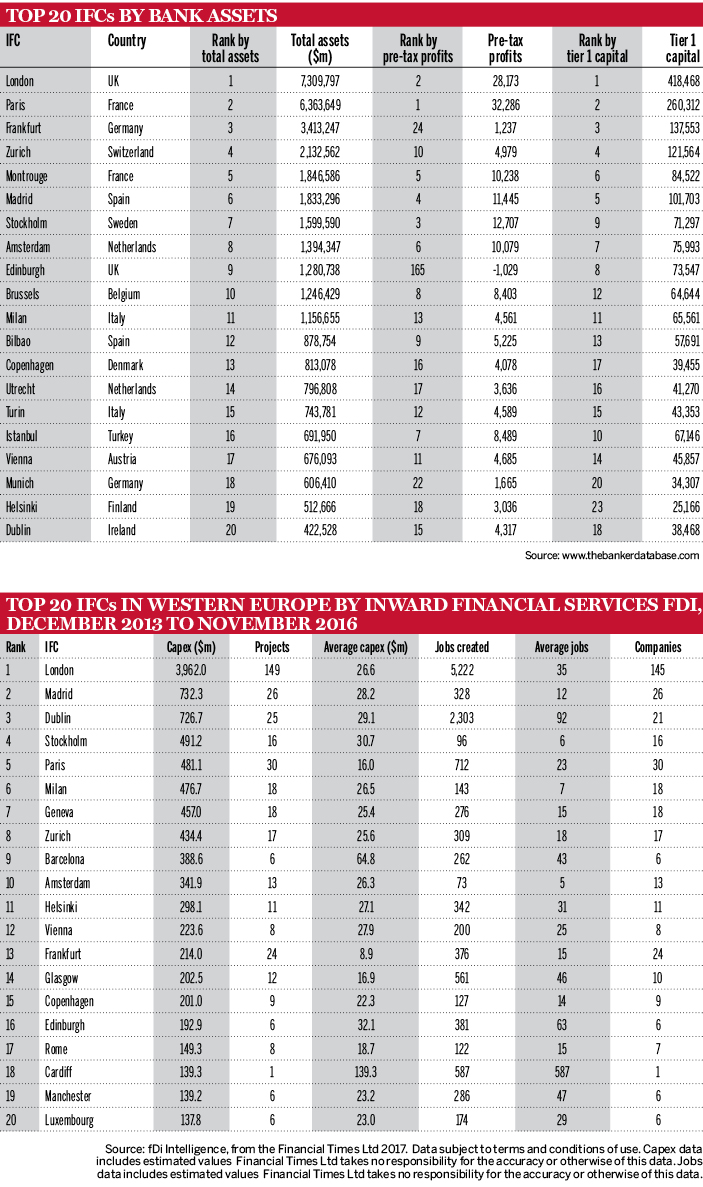

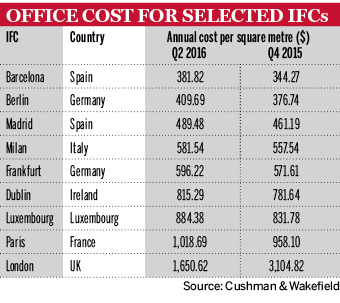

Hubertus Väth, managing director of investment promotion agency Frankfurt Main Finance, says the German financial centre has not only seen a rise in office space enquiries but actual contracts. In 2010 the average half-year figure for new office rentals was about 200,000 square meters, but the number for the second half of 2016 shot up to 350,000 square metres. “There are new rental [contracts, where tenants have yet to move in] from international financial services companies,” says Mr Väth. It should also be noted that office space in Frankfurt is just under one-third the price of that in London, although the UK capital’s office costs have halved in the space of just a few months, from the fourth quarter of 2015 to the second quarter of 2016.

London’s size, skills and financial network will be hard to match, but Paris is comparable in terms of the banking sector’s dimensions: $6.63bn of bank assets compared to London’s $7.31bn, according to The Banker Database, with Frankfurt in third place in Europe with $3.41bn.

Luxembourg and Dublin have become important players in the provision of fund services, holding €3626bn and €3839bn in assets under management and administration, respectively, according to industry statistics. This compares with about £6800bn (€7950bn) of assets under management for the UK, where many European investment managers tend to be located (rather than their asset servicing teams).

Madrid and Dublin attracted about €730m of foreign direct investment into their financial services sectors in the three years to November 2016, second and third among European centres after London, according to estimates by database fDi Intelligence.

Centres within the EU single market would be particularly appealing to new foreign firms, according to Mr Väth. “I don’t see headquarters [suddenly] moving to Frankfurt, but there are new incumbents, a few smaller banks, commercial rather than investment banks, that have been holding back their location decisions over the past 12 months [because of Brexit],” he says.

Although less tempted by continental Europe, US investment banks are still placing enquiries with regulators to clarify potential friction over the different treatment of products, such as derivatives. Goldman Sachs was reportedly looking to halve London staff numbers from 6000 and redistibute certain operations between New York, Frankfurt and other European centres, according to German newspaper Handelsblatt, plans which the bank would not officially confirm.

Berlin steps in

Other centres might enjoy increasing interest from smaller but fast-growing firms. Though at a different stage of growth, Berlin and Barcelona have been attracting increasing numbers of financial technology – or fintech – companies, and investors are paying attention. According to consultancy EY, Berlin start-ups received the highest volumes of financing in Europe in 2015 with €2.15bn, surpassing London’s €1.77bn. The report ‘Fintechs in Berlin: An Overview’, supported by Investitionsbank Berlin and published in August 2016, highlights the city’s potential in terms of technical skills and openness towards small entrepreneurs.

“What practitioners say is that it’s an ecological system, a combination of things that makes Berlin particularly attractive on a global scale,” says report author Volker Nitch, a professor at the Technische Universität Darmstadt. He adds that because of Germany’s fragmented financial services scene, in which Hanover and Hamburg also play a role, Berlin does not quite see Frankfurt, the country’s larger centre, as competition. On the other hand, proximity to the regulator, based in Berlin, plays in its favour.

“Many fintechs try to influence what government allows them to do, which is why Frankfurt-based people often travel to Berlin,” says Mr Nitch. “The general view is that Brexit will harm London and the question is who will benefit. There are lots of pitches going on to present a case for making it easier to relocate people to Berlin.”

Berlin’s appeal is often explained also in terms of its international community and buzzing social life, in the broader sense of what it offers residents. The same applies to other nascent fintech hubs. Opportunity Network founder and CEO Brian Pallas has chosen Barcelona as the main base for its operations. The company has created an online network that matches businesses with potential partners as well as financiers. Of nearly 90 staff, about 60 are based in Barcelona, with the remainder scattered between New York, London and cities in the 24 other countries the company targets.

Mr Pallas says that with the same salary he can offer employees a much more comfortable life in Barcelona than in London. According to Expatisan, an online service that compares locations’ cost of living, the Mediterranean hub is 40% cheaper than London, although Mr Pallas admits that prices are on the rise because of the recent influx of foreign businesses.

Bet on Barcelona

Antoni Massanell, CaixaBank deputy chairman and president of the Barcelona European Financial Centre (BCFE by its Catalan initials), also sees Brexit as a potential opportunity for hubs such as Barcelona, which can grow as service centres for the rest of Europe, and where the fintech sector has indeed expanded recently. According to the BCFE, while in 2012 all 79 local and international financial service companies based there were traditional firms, three years later, in 2015, 45 out of the 106-strong group were fintechs.

Mr Pallas adds: “Barcelona has a unique competitive advantage: great access to talent, capital, low cost of living, great transport connections, care towards facilitating the creation of fintech incubators. It’s one of the few cities in Europe that is not English mother-tongue where you get by both in English and in Spanish, which are also the two most spoken languages in the West. If I were to bet on a European Silicon Valley, I would bet on Barcelona.”

Italy's big hope

There are also centres that, irrespective of Brexit, hold largely untapped potential. Milan is a case in point. Italy’s main financial centre, Milan sits in a part of the country inhabited by large numbers of internationally successful small businesses. Traditionally struggling to raise funds, these companies offer both investment opportunities and an important engine of economic growth.

Nino Tronchetti Provera, co-founder and managing partner of private equity fund Ambienta, lays out a few figures: €397bn in private equity funds is invested in 26,000 companies in Europe between 2007 and 2015; 83% of these are small and medium-sized firms; 40% of investments come from outside Europe; Italy has 79,000 of such companies in the manufacturing sector alone, the highest number in Europe, ahead of Germany.

“If you want big companies you want to go to France, but this is the paradise of small and medium-sized enterprises,” says Mr Tronchetti Provera. “Italy should be the land of private equity, but in reality we don’t have private equity. In terms of investors, we’re worth zero. In terms of investments we’re worth half of Germany, a quarter of France, a fifth of the UK.”

The issue is mostly related to the carry interest, the performance fee paid to the investment manager once returns reach a certain level, which is not explicitly regulated in Italy and which leads to uncertainty over taxation. It also has to do with challenges in raising funds locally, because Italian investors, institutional investors included, typically look at products considered to be lower risk. There are also tax disincentives.

“If an Italian pension fund invests in government bonds, it pays 12.5% in tax and has no limits [to the size of the investment]. If it invests in private equity it pays 26% in tax and has a number of limits – it’s a folly,” says Mr Tronchetti Provera. Local regulators have scope to clarify this issue. Milan could serve as pivot for investors as well as other centres in Europe, as private pension funds struggle to meet their commitments in the current low-interest-rate environment.

London will, in all likelihood, retain its lead in Europe, but Brexit is encouraging the expansion of others. Mr Väth says that until now all European financial centres aimed at engaging with London but not among themselves, working as satellites to the main planet. “The satellites will grow and will start to interconnect and not purely focus on the planet itself,” he says. “There isn’t going to be a new planet that takes over, but the ring of moons will become bigger, more interconnected.”