Three years after undergoing its worst recession since World War II, Turkey has pulled back from the brink of economic disaster. Its recovery has been remarkable, and almost all trace of the crisis has been eliminated.

Radical reforms carried out by the conservative government of the prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, have reduced the role of the state in the economy and aligned Turkey’s political system with that of the EU. The country’s massive privatisation programme is moving full steam ahead. State monopolies in fixed line phone and data transmissions, natural gas importation, sales and distribution and electricity distribution have been lifted – representing a clean break from Turkey’s traditional past of state-dominated industries and services.

The Erdogan government has also moved forward with talks in Switzerland aimed at resolving the 40-year Cyprus conflict with neighbouring Greece. The reforms are designed to get a firm date for Turkey’ for the start of membership negotiations with the EU and to achieve sustainable economic growth in the coming years. Turkey forged a customs union with the EU in 1996. At its Helsinki summit in 1999, the Union named Turkey a candidate member country.

“Neither Turkey, nor the EU has a Plan B. So we assume that the EU’s present plan to start negotiations for Turkey’s membership in early 2005 will go on schedule,” Erdal Karamercan, president and chief executive officer of Eczacibas¦ Holding, a large conglomerate with interests in pharmaceuticals, personal care products, building materials and financial services, said in an interview.

Investors’ confidence in Turkey, which dissipated following the financial crises of November 2000 and February 2001, has returned as a result of these reforms, general improvements in economic conditions and political developments over Cyprus. Standard & Poor’s, on March 8, raised the rating on Turkey’s economic outlook to positive from stable and upgraded its rating on long-term Turkish lira credit rating from B+ to BB-, saying that Turkey’s debt payment capacity had increased. Credit rating agency Fitch also raised Turkey’s long-term domestic and foreign currency rating to B+.

On the up

Backed by the IMF, Turkey’s economy grew 5.2% in the first nine months of 2003, according to the State Institute of Statistics (DIE). A boom in exports, a rise in domestic consumption, an increase in industrial production and expansion of private investment contributed to growth of the gross national product (GNP). In 2001, the GNP declined 9.5% as a result of Turkey’s worst economic crisis since 1945.

Industrial capacity usage in January 2004 stood at 77.2%, up from 74.9% in the same month of last year, but down from 79.5% in December 2003, DIE reported.

Growth in 2003 was particularly strong in the automotive industry, which produced a record 562,466 motor vehicles, up 57% from 2002, the Automotive Manufacturers’ Association (OSD), a trade group, reported. In 2000, the previous best year for the industry, Turkey produced 430,947 vehicles.

Private investment in 2003 accounted for 73.4% of all investment in Turkey, up from 63.5% in 2002, according to DIE.

Economic planners were projecting 5% growth of 2003. This would make Turkey the fastest growing economy among the member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and also among the 12 other EU accession candidate countries – including the 10 states that will become members on May 1.

Inflation falling

Year-to-year inflation based on wholesale prices at the end of February 2004 stood at single digits for the time in 28 years. Inflation based on wholesale prices was at 9.4%, compared to 88.6% at the end of 2001. Year-to-year inflation based on consumer prices also fell to 14.28%, the lowest level in three decades. Inflation in Turkey in the past 27 years has averaged anywhere between 30% and 150%.

“The fall in inflation is good news and brings Turkey into a new era,” declares Ali Babacan, the economy minister. “Inflation not only tips economic balances unfavourably, it fans instability and uncertainty. Inflation results in the erosion of salaries, deepens inequalities in wealth distribution, and is the main reason for poverty and unemployment.”

The State Planning Organization forecast 5% growth in 2004 and inflation based on consumer prices at 12%. If realised, this would mean strong growth for the third consecutive year in Turkey. High economic growth is needed to reduce unemployment, which expanded during the crises to as high as 12.3% of the working population in first quarter of 2003, one of the highest in western Europe. Unemployment contracted to 9.4% at the end of 2003 as a result of robust growth.

Interest rates on three-month government bonds and Treasury bills in mid-March stood at the range of 19.25% and 24.9%, down from 193.71% in March 2001, the height of the financial crisis. The Central Bank, in mid-March, lowered interest rates two percentage points on short-term bank loans to 22%.

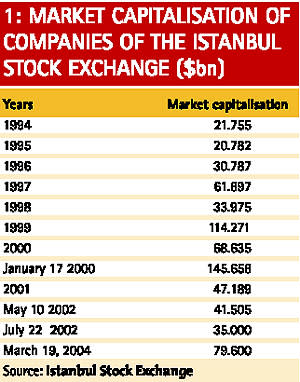

Optimism also prevails on the floor of the Istanbul Stock Exchange (IMKB), where share prices reached a record high of 20,472.61 points on February 25, up 9.9% from the beginning of the year. The bourse was the world’s best performing stock market in 2003 with the benchmark IMKB-100 Index rising 80%. Market capitalisation of the 287 companies listed on the stock exchange on March 19, 2004 was $79.6bn, up 127% from July 2002, when it was a mere $35bn, but still 45% off from January 17, 2000, when market capitalisation stood at $145.7bn. Scores of companies are lining up to go public in 2004 if the recovery on the equities market continues. Turkey’s number one sports club and top soccer team, Fenerbahce, went public in January.

Export boom

Turkey’s exports rose 30% to a record $46.878bn in 2003 while imports climbed 33.3% to a record $68.734bn, according to the Undersecretariat of Foreign Trade. A boom in sales of ready-wear and textiles, motor vehicles, household appliances and home electronics and other durable consumer goods has driven exports, while increased purchases of raw materials and semi-finished products have fuelled imports. Turkey exported a record $16.6bn in ready-wear and apparel, textiles, carpets and leather products in 2003, a 25 6% increase from 2002, the Istanbul Textile and Apparel Exporters’ Association (ITKIB), a trade group, reported. At the end of 2003, Turkey had a current account deficit of $6.8bn, up 3.5 fold from 2002.

In 2003, Turkey exported a record 347,119 motor vehicles, including 213,857 automobiles, up 35% from 2002, to 107 countries, according to the OSD. The country earned a record $7.2bn in automotive sector (motor vehicles and components) exports in 2003, a 49.8% jump from 2002. Exports have risen despite a strong Turkish lira.

“The lira’s strength since the war in Iraq has largely been driven by the country’s improved macroeconomic and political fundamentals. In particular, the government’s successes in reducing inflation and the progress in EU-inspired reforms have boosted domestic investor sentiment, fuelling demand for lira-based assets,” Mehmet Simsek, an emerging markets analyst with Merrill Lynch, writes in a report on Turkey.

Shock absorber

The fall in inflation, the drop in lending rates and overall improvements have made the Turkish economy less susceptible to internal traumas and external shocks. Volatility in the economy has all but disappeared.

The war in neighbouring Iraq last May, and bombings in Istanbul of HSBC Bank’s local headquarters and British Consulate, as well as blasts at two Jewish synagogues last November that killed more than 150 persons, had little effect on the economy.

“Events such as these would have triggered an economic crisis in Turkey in the past,” says Tolga Egemen, deputy general manager of Turkiye Garanti Bankas¦, a large commercial bank. He says that lower inflation and reduced borrowing costs had made the Turkish economy resilient.

Weight of debt

Yet some of the problems that triggered the November 2000 and February 2001 financial crisis persist. The Turkish government is still carrying a huge stock of domestic and foreign debt. Turkish government’s domestic and foreign debts totalled $216bn at the end of February 2004, up 45% from end 2002, according to the Undersecretariat of the Treasury.

The government’s foreign debt stood at $64.2bn at the end of February, but these were mainly medium and long-term and posed no real problems. Domestic government debts, which stood at $151.7bn, continue to spiral upwards and present a major headache for the Erdogan administration. Domestic government debt in December 2003 stood at $139.3bn. Although interest rates have fallen drastically, these debts are still very short term – they have to be paid back in less than a year. The government has been paying off these debts with new borrowing. Some 52%, or $34.928bn of state revenues of $59.7bn in 2003 alone went to interest payments on its domestic debt (see table four).

Turkey had a budgetary deficit of $22.7bn, slightly more than in 2002 because of increased tax revenues.

In 2004, the Treasury aims to borrow $120.6bn to service $136.460bn in interest payments, according to the Undersecretariat of the Treasury. The government plans to borrow some $10.8bn from abroad and raise $109.8bn from the domestic market.

The government intends to further reduce interest rates on government bonds and treasury bills and lengthen the maturities on its debts to ease financial pressure against the Treasury.

Some industrialists have warned, however, that Turkey will not be able to sustain its export drive because of the strength of the lira against the US dollar and other western currencies. Turkish export products, such as ready-wear and apparel, they say, are rapidly losing their competitiveness, against products coming out of China and other Far East countries because of the strong domestic currency. Apparel and textiles account for one-third of Turkey’s total exports.

As regards the currency the lira has gained 23.7% value against the US dollar since March 21, 2003, and 7.7% since the beginning of the year.

“No one is pleased with the rise in exports,” the newspaper Dunya said in a survey on the clothing and textile industry published in February.

“Exporters are selling their products at a loss,” says Celal Sonmez, president of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Bursa, a large industrial city in western Turkey “If we want to take our place in world markets, we can’t go anywhere with weak foreign currencies.”

Ilhami Ozturk, secretary general of Coats Turkiye Iplik Sanayi, a British-owned yarn manufacturer with plants in Turkey, adds: “Exporters can continue selling abroad under low foreign currency rates by renouncing profits for a short period of time. But this can’t continue forever.”

IMF programme

An IMF-financed agreement that Turkey put into force at the end of 1999 had to be readjusted because of the economic crises that rocked the nation in November 2000 and February 2001. Supported by $31.5bn in standby loans, the agreement was extended to the end of 2004. Under the agreement, the government introduced a stability programme that included a floating exchange rate system and a restructuring of the country’s ailing banking system. The government also carried out other structural reforms and bought discipline to public finances. The Central Bank was made autonomous.

Since 1997, a receivership fund (TMSF) operated by the Central Bank has taken control over the affairs of 23 shaky private banks. Several of these banks have been merged, privatised or shut down. The collapse of these banks has cost Turkish investors and tax payers nearly $70bn. The former owners of six of the failed banks agreed on March 25 on a timetable to repay their debts.

Turkey’s National Assembly in January made changes to the country’s Banking Law so that banking authorities can seize the assets of the owners of the failed banks if they do not pay up their debts to the TMSF. The fund used the legislation on February 14 to seize the 219 companies of the Uzan Group, one of the nation’s biggest industrial and telecommunications conglomerates, because the owners failed to come up with a plan to pay back their $5.8bn debt to the TMSF over the failure of their Imar Bank in summer 2003.

Four former private banks are currently under the control the Central Bank’s Savings Deposits Insurance Fund: Toprakbank, Pamukbank, Adabank and Bay¦nd¦rbank.

Under structural reforms, the government has eliminated 49,000 public sector jobs since 2002, and speeded up the privatisation of state enterprises. A hiring freeze was imposed on civil service jobs, and the tax administration is being reformed. Independent regulatory bodies were established to supervise banking, telecommunications, energy, tobacco and sugar.

Monetary policy

The Central Bank has kept the floating exchange rate system going to bring inflation and bank lending rates down in 2003. Foreign exchange rates are determined by market conditions, but the Central Bank buys or sells foreign currency or Turkish lira from the market to prevent disruptive exchange rate fluctuations from taking place.

During last year’s Iraq War, the Central Bank provided low cost loans to banks that were facing a liquidity squeeze. In November 2003, in the wake of the Istanbul terror bombings, it lowered its prime lending rate and opened credit lines to all banks that needed injections of liquidity. The quick action reduced tension in money markets and allowed the debt system to operate efficiently without any payment problems.

The Central Bank also lowered interest rates on short-term loans six times in 2003. The bank lowered interest rates on overnight loans from 26% to 24% in the interbank market on February 2004 due to lower inflation figures. The Central Bank reduced the interest rates on the lira reserves the banks must keep four times in 2003 from 25% to 16% at the end of December 2003.

The bank also intervened in the foreign exchange market six times in 2003 to prevent excessive exchange rate fluctuations by buying and selling foreign currency. From May to the end of September 2003, it had acquired $9.9bn, the largest amount ever it purchased in a single year. The bank absorbed another $2.1bn in excess liquidity in February this year, further strengthening the Turkish lira and increasing its hard currency reserves.

Foreign investment

One of the aims of the government’s stability programme is to attract more foreign investment. Excluding investments in telecommunications and energy projects, the total foreign investment that entered Turkey from 1954 to end of June 2003 was a mere $16.3bn, about half of the total foreign investment China alone attracts in a single year, the government’s Foreign Capital Directorate reported.

Turkish companies made more investments abroad in 2003 than that entered the nation. Turkish investments abroad totalled $499m in 2003, while direct foreign investment reached only $172m. Nevertheless, an influx of foreign investment in recent years has taken place in large-scale energy, and telecommunications projects and in banking.

On February 24, 2004, the German-owned $1.5bn Sügözu Thermal Energy Plant began operating in Iskenderun, on the Mediterranean Coast. The 1210MW plant, which will produce 7% of Turkey’s annual electricity requirements using imported coal, has become the biggest German investment in Turkey and one of the biggest foreign investments in the country to date.

The German contractors Steag AG and Power AG constructed the power plant in four years under a Build-Operate (BO) contract. Iskenderun Enerji Uretim, a company which the two contractors formed, will operate the plant that will produce nine billion kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity every year.

An Italian-Turkish joint venture, Turk Telekom Italia (TTI) was officially inaugurated in February to operate a mobile phone network after a merger between Turk Telekom’s Aycell GSM network and the IS-TIM mobile phone network. Telecom Italia Mobile (TIM) and Turk Telekom, the state fixed phone line operator, each own a 40% stake in the operation and Turkiye Is Bankasi, one of Turkey’s two biggest private banks, has a 20% interest.

To attract foreign investment, the government invited the top executives of 20 multinational corporations to Istanbul for a round table conference on March 15, 2004. Those who took part in the conference included Lewis Booth, chairman of the Ford Motor Co, Steve Pusey, chairman of Nortel Networks of Canada, and Guiseppe Morchio, chief executive officer of Fiat of Italy.

Italy’s Banca Intessa, in March, resumed negotiations with Turkey’s Dogus Group to acquire a 51% stake in Turkiye Garanti Bankas¦, one of Turkey’s biggest commercial banks, for an estimated $1.5bn. Talks between Italy’s biggest bank and the Dogus Group, which has interests in retailing, tourism, motor vehicle distribution, contracting and banking and finance, had been interrupted following the September 11 terror attacks. If a deal is concluded it would make Banca Intessa the biggest Italian investment in Turkey and attract more foreign investment into Turkish banking, financial, analysts say.

“If an agreement is concluded with Garanti Bankasi, this will bring an increase in foreign investment not only in banking but to other sectors as well,” Didem Gordon, deputy general manager of Kocbank told Reuters.

In addition to direct foreign investment, a total of $2.3bn foreign investment entered Turkey through mergers and acquisitions in domestic equities.

Projections for 2004

Major steps were taken in 2003 to allow Turkey to roll over its domestic debts, bring inflation under control, achieve sustainable economic growth and complete its structural reforms. If Turkey is able to continue its stability programme through to the end of 2004, it will have successfully completed an IMF-backed programme for the first time ever.

This programme, which will carry the country to 2005, will further influence Turkey’s relations with the IMF and the EU.

It will become clearer at the end of the first half of 2004 whether Turkey will need additional IMF financing. Turkey’s ties with the EU will also depend on the country’s economic situation and the outcome of talks on Cyprus. The European Commission’s Regular Report on Turkey, published on November 5, 2003, serves as a road map for Turkey’s road towards EU membership. The heads of state of the EU countries, including the 10 states that will join on May 1, will discuss whether to begin membership talks with Turkey at a summit in December this year. Several countries, including Greece, have announced that support for Turkey is unlikely if the Cyprus problem is not settled by then.

The Regular Report lauded Turkey for its bold decisions and structural reforms and the market regulatory agencies that have been formed for strengthening the country’s market economy. The report particularly praised the country for strengthening the supervision of the financial sector. The report also noted the transparency of the management of the financial system, and improvements in the sector, and stressed the need for the continuation of the fight against inflation, restructuring of the banking sector and further liberalisation of money markets.

New currency

One of the major projects of the Central Bank of Turkey at the end of 2004 will be the creation of a new currency with the millions knocked out. The new Turkish lira is expected to create the psychological conditions to further help inflation drop. The government will introduce the new currency in January 2005.

Turkey has set its national budget at $113.717bn in 2004. The government is projecting exports to rise to $51.5bn and import to climb to $75bn in 2004. It is expecting a current account deficit of $7.6bn (2.9% of the GNP) in 2004 after deducting revenues from tourism and other services, suitcase trade, remittances from Turkish workers living abroad and direct foreign investment, and investment into the equities market.