Global transaction banking can be a huge profit driver for banks. But plain vanilla transaction processing services are no longer to the corporate palate. The global liquidity crisis, banking scandals, as well as new trade corridors and growth opportunities in emerging markets, have made corporate treasurers far more picky.

Editor's choice

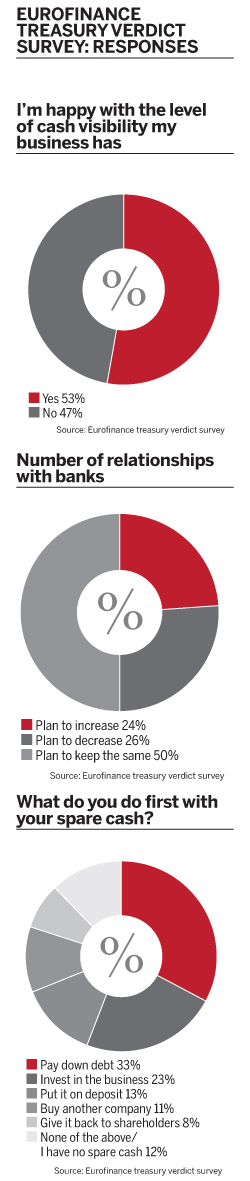

The search for trustworthy, stable banking partners that both understand local legislation and offer appropriate services, has resulted in a more concentrated approach to banking partners and a focus on being, technically, bank agnostic. But corporates remain vigilant, as was evident from a survey held during 2012’s Eurofinance conference. Only 9% of treasurers reported that they were more confident about the global economy than a year ago; 71% remained sceptic.

“In the current climate, we have to be careful with the banks we deal with,” says David Felton, treasurer at steel trader Stemcor. He uses the company’s treasury management system to track the banks’ ratings, how much cash or borrowing his company has with each bank and what country each bank and its parent is in, so that Stemcor “can transfer the money out of that account instantly if [it] want[s] to”.

Fewer relationships

This approach of parking cash with safe banks while requiring the option of instant money outflow puts pressure on banks to separate operational and non-operational balances to meet the liquidity coverage ratio and net stable funding ratio obligations under Basel III. As banks have to re-classify balance types under Basel III and certain types of deposits become more valuable to them, the relationship among corporates and banks continues to change – and is not only driven by corporate demand, but also by what banks are able to offer. If a bank gets it right, it can optimise its net interest income from the global transaction banking (GTS) business.

“We are reducing the number of bank relationships so we can give the fee-earning business to banks that lend to us,” says Mr Felton. He found 800 accounts with more than 100 banks worldwide when he started his role in January 2011, 150 of which were not even on the company’s official registry. “I closed 65 in the first month – they had not been used for years. Often, local boards, directors or local treasurers opened accounts with relationship banks in their area, which didn’t necessarily fit in with the overall relationship structure of the group. A lot of companies are in this situation. Now, nobody at Stemcor can open accounts without my authorisation.”

Besides the bonus of cost savings and greater transparency, this focus on core banking partners has evolved as a key risk mitigation strategy for corporates. Siri-Anne Dos Santos, head of cash management operations at chemical company Yara International, says: “Until the crisis, we wanted to consolidate our bank numbers to about four core partners. When the crisis hit, we realised we would benefit from partnerships with banks for our main currencies."

Yara International, which is present in more than 50 countries and sells to over 120 countries, now has roughly two banks for each main currency and seven to eight core banks for cash management. “We don’t want to be tied down with just one or two banks. We need back-up, in case something goes wrong,” says Ms Dos Santos.

Swift solution

This changing mindset has manifested itself in corporates’ technology platforms, too. Large corporates are pushing for more industry solutions or shared platforms, such as SwiftNet and payment hubs, says BNP Paribas’ head of global transaction banking, Pierre Veyres.

“This evolution is taking place at different levels, from global to local. In China, for instance, we propose a multi-bank platform to manage clients’ cash across various banks through one entry point via us. The convergence of cash and trade on the corporate side has been a strong rationale for rethinking the traditional transaction banking model,” says Mr Veyres, adding that some banks still prefer a silo approach.

The bigger corporate trend is to join the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Communication (Swift), a financial institutions-owned co-operative that was originally established for interbank financial communication. Using a Swift service bureau, usually one by a non-bank financial technology provider such as SunGard, corporates become bank agnostic and only need to plug in to SwiftNet, the communication system, in SwiftScore, the user group for corporates. The Swift service bureau translates all financial files into the Swift messaging ‘language’, thus liberating corporates from banks’ propriety systems, which require individual passwords, different contract agreements and different levels of security.

“The reliability with Swift is better than banks' propriety systems. Membership isn’t cheap, but it is worth it if you have a larger bank base and payment volumes,” says Mr Felton.

Happy adopters

Among the many corporates that have adopted Swift is multi-industry technology producer Johnson Control, which is now live with SwiftNet in more than 60 countries. Mario Del Natale, director for treasury operations, systems and applications at Johnson Control, emphasises that the company always uses the same format within a single standard, as set out in the Swift rulebooks, and only deviates to satisfy country-specific requirements, not bank-specific ones.

“The approach to SwiftNet varies from corporate to corporate. Ours is to use one format to communicate with the banks. We only work with banks that are able to work with the required format," says Mr Del Natale. This approach significantly reduces the level of complexity in terms of interface and communication channels maintenance, as well as overall IT costs, because the company has several enterprise resource planning systems, he says.

Where does this leave the banks? In Johnson Control’s case, it built a payment hub with banks that were technically able and ready for it.

“The payment hub minimises the number of connections with the banks and the Swift costs," says Mr Del Natale. "For instance, we have relationships with Citi in different countries, such as China and Argentina. Instead of sending the payments to Citi China and Citi Argentina... payments are sent to our Citi hub located in Belgium [via SwiftNet] where Citi routes the payments internally to its subsidiaries. With SwiftNet, we are able to obtain better visibility on the cash position and bank flows. So we are able to negotiate flat bank fees and better manage our liquidity."

Finding cash

Treasury has thus become more than a cash management business. It is seen as an in-house bank among many corporates. Treasurers look for untapped cash within their own company – and to some extent trapped cash in different regions – to minimise their exposure to banks, reduce borrowing and optimise their working capital.

Marianna Polykrati, group treasurer of Greek food and beverage company Vivartia, characterises this breed of treasurers who unlock cash with little reliance on banks. When bank-backed working capital finance dried up in the troubled Greek economy, causing Vivartia to scale back its international business, it began using factoring for its receivables and forfeiting for its payables, offering higher discounts for early payments and a premium for extended payment terms. It also uses intercompany loans strategically, thanks to amendments to a law in Greece that previously only allowed the parent company to lend to direct subsidiaries.

“We try to optimise the asset structure of the business. When we have a business unit that provides no further growth for the company, we obtain offers for its sale and use the cash to grow a more profitable business [division]. We also plan to merge several of our smaller subsidiaries to free up more cash, starting in mid-2013 and completing in 2014,” says Ms Polykrati.

Vivartia does not currently have a treasury management system (TMS), but Ms Polykrati has found a couple of solutions that could be tailored to Vivartia’s needs. “Our group currently consists of 125 legal entities with approximately 450 bank accounts at 10 different banks," she says. "We want to use a TMS to improve the cash-flow forecast procedure, and eventually for derivatives products [as we] are trying to exploit opportunities that could help us grow bigger and stronger than before the crisis.”

Cross-border complications

At Stemcor, Mr Felton established treasury as the in-house bank and counterparty for its subsidiaries, foreign exchange (FX) trading and to pave the way for a centralised cash pooling system. “I wanted to get all our credit balances into one place to use them effectively to pay down external debt. I also wanted to streamline the hedging of our FX because each of our companies was doing it with their local bank, which was often expensive and also inefficient,” he says.

Now Stemcor keeps a cash pool account in Amsterdam to which its sub-accounts are linked. This way all debit and credit balances are notionally netted into a head account, so every subsidiary benefits from the aggregated cash balance and can withdraw credit up to the total collective sum. The actual cash stays in the individual accounts, so that the company avoids any cross-border transaction tax and FX issues.

“As corporates operate in more and more markets and have to fund more accounts, their cash account structure gets fragmented. Notional pooling allows them to reap some benefit despite this fragmentation,” says Standard Chartered’s global head of product management for transaction banking, George Nast.

Yara’s approach is different. It operates its cash pool on a zero balance account basis, the physical sweeping of cash positions from the sub-accounts into one main account. It has set up internal rules, such as the payment of intercompany loans before the due date if the debtor subsidiary in a remote or exotic country has surplus cash on its accounts.

But legislation in some hot-spot markets such as India, China and Africa can make cash pooling a complex matter due to currency restrictions. Although it is possible to repatriate this ‘trapped’ cash from these markets, it is cumbersome and there are a lot of regulations that govern it, says Mr Nast. He sees a growing demand among corporates to liberate that cash or make optimal use of it locally.

Corporates could, for instance, convert a currency into another under local legislation or draw a loan against that excess cash if permissible to use it for other business purposes.

SEPA's influence

Citi’s head of payments and receivables for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, Karin Flinspach, is confident that in Europe, the Single European Payments Area (SEPA) reduces concerns about trapped cash as it enables free and fast cash movements. But as outlined in an article in The Banker’s October issue, there are many technical hurdles to overcome before the 2014 deadline that thwart SEPA’s efficiency.

Mr Felton is one of a number of treasurers to doubt that SEPA will improve anything for him from a technical or operational perspective. “I already have everything consolidated and concentrated where I want it [in the cash pool]. The domestic account is linked by target balancing into the cash pool and I am moving money back and forth using Swift,” he says.

Although Stemcor’s cash pool is located in Amsterdam, it maintains at least one business account per country to handle local paper payments, payroll, direct debits and credit transfers. The cash pool supports the euro, but also all currencies Stemcor needs, and the main transactional banking takes place in the cash pool. “Visibility on cash balances gives corporates the ability to optimise risk and yields, especially for excess balances,” says Mr Nast. “If you have excess balances in a restricted currency market, we might give the client benefit for a notional pooling arrangement, with better interest rates. Even when you can sweep cash easily, many clients prefer notional pooling because it allows them to maintain balances in accounts they want to keep funded.”

Major change ahead

This preference is not to every bank’s liking. “Low or even negative yields for good rated paper, money market deposits and money market funds is leading to a situation where more and more clients leave their balances on a current account," says Christian Goerlach, director of asset and liability management for Europe at Deutsche Bank. "We can see it at the European Central Bank where a number of banks stopped using the deposit facility once the rate was lowered to zero.”

It is the combination of low liquidity value, low short-term rates and the pressure in the industry to reduce balance sheets that make these kinds of non-operative balances increasingly unattractive for banks to hold, he says. “Recently, the Danish krone short-term rates turned negative. This isn’t something we have in the euro now, or would expect to see for operational balances in the near future – unless there is a material economic deterioration,” Mr Goerlach says.

According to John Salter, Lloyds Bank's head of cash management and payments, Basel III could lead to major changes in currency pooling near 2015. “Basel III is forcing a re-classification of balances and an even greater focus on the costs associated with pooling. This could lead to some banks reducing or exiting specific services, such as cross-currency pooling,” says Mr Salter.

Corporates with multiple currency positions would then have to physically use currency swaps or FX to manage positions. Banks could alternatively pass on the cost for these services to corporates. “Treasurers would need to revisit the overall business case for using such services. The cost increase could be many multiples of the current fees,” says Mr Salter.

Consequently, different types of balances combined with traditional pooling and sweeping services will have different economic benefits to banks. It will no longer just be corporates who are vigilant, but also banks. Corporates will need to understand this, as what becomes important for banks will become important for corporates.