While banks say low interest rates hit their bottom line, not everyone – including the IMF – agrees there is a link. Danielle Myles analyses the data.

Ever since central banks cut interest rates to record lows in 2009, bank bosses have claimed that the policy has hurt their profitability. Among the most vocal are those headquartered in the eurozone, the UK and Switzerland, which have endured ultra-low, if not negative, rates for longer than their US counterparts.

When policy rates fall, it is logical that lenders’ interest income and expenses also fall. Unless they are willing to pass on negative rates, which only a handful have done, the amount banks can pay savers is floored at 0%. This means that higher rates allow banks more leeway to achieve higher spreads, or net interest income (NII), while low rates squeeze NII. Or so the theory goes.

But the relationship between policy rates, NII and net interest margin (NIM), which measures the total interest generated from a bank’s average earning asset, is not proven. An International Monetary Fund working paper from earlier this year found that “NIM remained broadly stable over the financial cycle” and concluded that “the much-discussed adverse effects of the low-interest-rate environment on bank profitability are not visible in our data – or at least not yet”.

A lack of uniformity

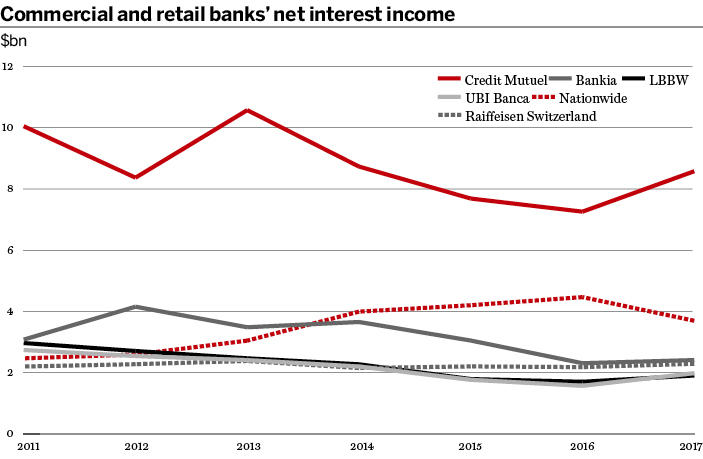

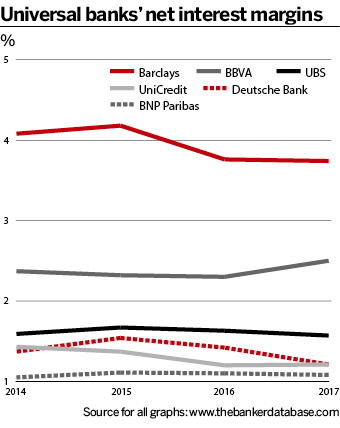

Data collected by The Banker on a sample of full-service and smaller lenders from Europe’s major markets reveals a general downward trajectory in NIM and NII. But the results are far from uniform. The one rather unexpected consistency is that, except for Deutsche Bank and the UK’s Nationwide, each bank’s NII picked up in 2017. The fact that Nationwide’s figure grew year on year until 2016, however, makes it the sample’s best performer. Bigger compatriot Barclays’ NII was relatively steady until two years ago when it dropped by 30%. Its NIM followed a similar path in recent years, although is notably higher than the sample’s other big banks.

Raiffeisen Switzerland’s returns are also commendable. Irrespective of its leadership crisis following a criminal investigation of former CEO Pierin Vincenz, the country’s biggest mortgage provider has maintained steady NII despite three years of negative interest rates. UBS’s NII has staggered downwards but its current NIM is just a fraction lower than in 2014.

In France, BNP Paribas’s NIM has followed a similar trajectory, although it’s higher today than three years ago. As with smaller compatriot Credit Mutuel, its NII staggered downwards for five years before spiking by more than 10% in 2017. Yet the latter, which has one of the country’s biggest retail banking networks, managed to grow its NIM over the past two years.

Elsewhere in the eurozone, UniCredit and Deutsche Bank’s NIIs have slid since 2011. BBVA’s, however, has been relatively stable, no doubt buoyed by its foreign network of branches of subsidiaries, many of which are in markets without low rates. Mid-size Spanish lender Bankia’s NII was steady before plummeting to a low in 2016. Meanwhile, Italy’s UBI Banca and German LBBW’s figures steadily declined over the same period.

Other factors at play

While lower NII and NIM coincide with lower interest rates, the effect is exacerbated (or sometimes mitigated) by other factors. The weak economic environment that prompted low rates in the first place could hurt banks in the most underperforming economies, such as Italy. Lenders in overbanked, and therefore hypercompetitive, markets such as Germany may find it particularly difficult to pass on lower rates to creditors.

The particularities of Switzerland’s real estate market have allowed its banks to offset lower deposit income with higher mortgage income, although retail banks in other markets have been hit by mortgage refinancings. Bigger banks that operate many business lines, meanwhile, can adjust the nature of their operations to combat the effect of low rates. One upside for all, however, is that low interest rates mean fewer loan defaults.

All data sourced from www.thebankerdatabase.com