The byzantine accounting rule introduced much volatility into the earnings and has finally been repealed by the US Financial Accounting Standards Board.

In the early days of January 2016, the US Financial Accounting Standards Board repealed the much-maligned debt valuation adjustment (DVA) rule. The rule was introduced back in 2007, with the theory being that there should be a link between the value of a bank’s own debt and the value of its wider liabilities. For instance, if bank debt loses value, the bank’s liabilities should also reduce as it could technically buy back its own debt on the cheap.

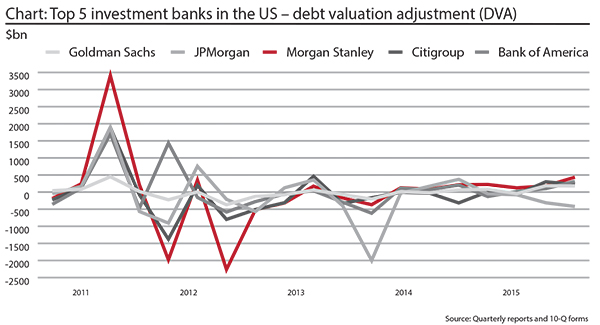

Despite the initial enthusiasm – DVA was at first championed by the Wall Street itself – banks came to resent the rule after it introduced major earnings volatility in the aftermath of the crisis (see chart).

During this recovery period, credit spreads for banks became jumpy. This was directly reflected in quarterly results, albeit in a counter-intuitive way; whenever credit spreads widened, banks posted a DVA gain; whenever they dropped, a DVA loss. In the third quarter of 2011, the five big US investment banks jointly posted a $9.35bn profit from the DVA alone, on the back of falling credit worthiness.

The biggest winner from rising credit default swaps (CDS) spreads was Morgan Stanley, which posted a record $3.41bn DVA gain in that quarter, with JPMorgan and Citigroup showing a DVA profit of $1.9bn. However, credit quality bounced up quickly at the banks and the third quarter of 2012 was one of the worst across the board, with Morgan Stanley showing a nearly $2bn DVA loss and Citigroup $1.38bn.

Starting in 2014, the impact of DVA steadied. Earnings at large investment banks no longer thrust institutions deep into the red or propelled them into the black by this accounting measure. With the exception of JPMorgan. In the first quarter, the bank implemented a funding valuation adjustment (FVA) framework, which aimed to include the present value of the market funding costs in its derivatives portfolio, and has reported DVA and FVA figures jointly since.

Apart from smaller shifts in credit spreads, one reason for reduced volatility in DVA could be the increased hedging executed by banks. This can be done by selling CDS on peer institutions, as these act as a proxy for the failure of one’s own bank.

While most of the lenders did not advertise their hedging practices, Goldman Sachs has disclosed in the past that it inoculated its balance sheet against swings in DVA. The bank said that it sold CDS on an unspecified peer group – other large US investment banks would fit the profile. Goldman Sachs has notably enjoyed smaller and steadier impacts from the DVA; the bank posted the smallest adjusted gains in the third quarter of 2011, when DVA at other banks was rallying, and a relatively small loss of $370m during the general downturn one year later.