The World Bank president talks about his ambitions for more vigorous and effective development finance, from tackling climate change to the need for debt transparency, particularly from China.

It may be an uncomfortable truth, but major crises can usually be good for the World Bank.

As developing countries around the world struggled to contain the spread of the coronavirus pandemic, the World Bank propped up governments’ healthcare efforts and alleviated the economic bite of Covid-19 by making available $160bn through a fast-tracked programme.

The funds are sorely needed. The World Bank estimates that this crisis will push 150 million people into extreme poverty and shrink the global economy by 5.2% in 2020 — the deepest recession in decades, at a time when many of the countries it works with already face extreme budgetary pressures. Zambia, Suriname, Ecuador, Belize, Lebanon and Argentina could not avoid defaulting on their sovereign debt obligations in 2020.

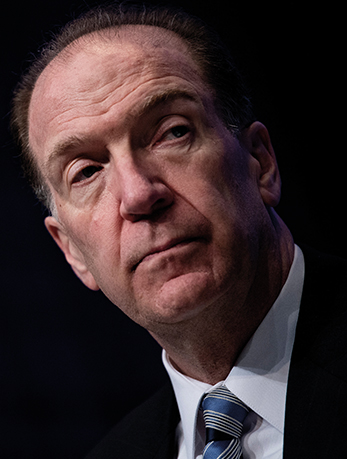

The relevance of multilateral support can hardly be overstated during global crises of this magnitude. But at a time in which donor countries’ own public finances are suffering, and with new types of risks to consider, Covid-19 is prompting the world’s largest development lender to adjust the way in which it fulfils its mandate. “We’re using all of the bank’s capacity right now in order to provide resources and to help countries get through the crisis,” says the World Bank’s president David Malpass in a phone interview with The Banker. “At the same time, we’re looking toward some kind of resiliency in the recovery.”

The inequalities of this crisis are particularly problematic, he says, “both for the immediate circumstances but then also for development in the future”. Inequality within and between countries is getting worse. While the world’s largest economies were able to spend the equivalent of about 20% of their gross domestic product (GDP) in monetary and fiscal stimulus in response to the pandemic last year — about $11tn according to World Bank estimates — the world’s poorest countries could only spend between 1% and 2% of their much diminished annual national output.

Fast-tracking recovery

By the beginning of April, the World Bank had released the first set of fast-track measures, disbursing $1.9bn across 25 countries as part of its Covid programme to alleviate health, social and economic shocks over the following 15 months, and which specifically includes $50bn worth of grants or loans at highly favourable terms for the world’s poorest and most vulnerable countries. By mid-May, 100 developing economies benefited from the initiative, says the bank. And in October, the programme included a $12bn project to help them buy and distribute vaccines with the aim of inoculating up to one billion people.

But the areas where Mr Malpass has spent much of his energy have been around debt relief and transparency. Along with Kristalina Georgieva, head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), he campaigned with G20 countries to cancel or restructure official and commercial debt owed by struggling governments. This led to some controversy, but also some groundbreaking results.

The G20 and the official creditors of the Paris Club eventually agreed on the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which, in place since May, first allowed 73 countries to suspend repayments on bilateral loans due in 2020. In October, the measures were extended to June 2021. And as of November, nearly two-thirds of eligible countries had applied to suspend loan repayments worth about $5bn. None approached bond investors, however, as noted by the Financial Times.

Mr Malpass insists that this should be rectified, otherwise any additional lending, including from the World Bank, would end up repaying foreign interest rather than fuelling development programmes. But some have argued that the DSSI is inherently flawed. To begin with, it excludes middle-income countries, many of which have suffered catastrophic consequences of the pandemic, such as Peru.

Some commercial creditors and debtor countries have also complained about being excluded from the initial G20 and Paris Club talks. And the Centre for Global Development (CGD), a Washington think tank, doubts the World Bank will actually disburse all the emergency funds it has made available by June 2021, adding that some countries are paying more to the bank in terms of existing loan obligations than they are receiving in new funds. The World Bank says that in all cases, flows to the world’s 73 poorest countries have been net positive, without providing information about individual cases.

Increased transparency

Other observers have also criticised how long it took for a broader agreement on a common framework to assess developing economies’ longer-term debt sustainability to emerge, in November. One reason, they say, is a lack of international coordination and co-operation, and not knowing who was in charge: the World Bank, the IMF, the G20 or the Paris Club. Although reinvigorated by the crisis, the World Bank’s lead on broader issues has not quite emerged. But the institution’s work did create some important breakthroughs. A bonus of the DSSI is that everyone who signs it, creditors and borrowers, also commits to full disclosure and transparency in the terms of their debt.

This is another important point for Mr Malpass. With Covid-19, he has been increasingly vocal about the necessity of transparent debt agreements. His staff are keen to note that the World Bank’s president has worked on these subjects for most of his career, including during the Latin American crisis of the 1980s — the region’s ‘lost decade’ — when a series of events led to many countries’ failure to service foreign obligations and to 10 years of painful stagnation. At that time, Mr Malpass served at the US Senate and then at the Treasury Department, lately as deputy assistant secretary of the Treasury for Developing Nations.

There are fresh concerns that the pandemic risks pushing Latin America into another lost decade, and that governments in other regions risk racking up debt that they will be unable to repay. Because of opaque agreements, it will be impossible to properly evaluate their sustainability and offer adequate support. “This is an important challenge for the world: as governments borrow, there is a reluctance sometimes by either the lenders or the borrowers to be fully transparent on the terms [of the loans], and that extends even to developed countries,” says Mr Malpass.

He holds specific concerns about China. “China has been expanding its lending over the past decade and that can contribute to development, because they’re often lending to poorer countries, to middle-income countries. But I think it can have an even more positive impact by being more transparent,” he says.

China can have an even more positive impact by being more transparent

On various occasions ahead of the G20 meeting this November, Mr Malpass lamented both China’s initial partial involvement in the DSSI, as well as commercial lenders’ reticence. In a November opinion piece published in the Wall Street Journal he wrote that “relief so far has been less than anticipated because not all creditors participated. Bondholders and other private creditors have generally continued to collect full repayments throughout the crisis while China’s participation was partial in scope.” He also recognises the Asian giant’s progress on the matter, however, which by the end of November had agreed on $2.1bn worth of debt relief.

He is hopeful more progress will come in terms of transparency, and from other countries too. For example, while some oil-exporting countries have not always been open about the terms of the foreign contracts that they have entered into, things are beginning to change. Ecuador has begun to disclose historical agreements and, even if backward looking, this is a helpful move towards transparency, says Mr Malpass. “It is very helpful, I think, for the people of Ecuador as they begin to see the commitments of their resources. But then it will also be useful for future growth [as it creates some foundation so that] future contracts can be more transparent,” he says.

Going green

In its quest to a more sustainable role for development finance, the World Bank has ramped up its message in relation to another key issue: climate change. For some, this may have been a welcome change from the few months after Mr Malpass took over the institution’s leadership in April 2019. His unchallenged nomination by now outgoing US president Donald Trump led to what some officials described as self-censorship within the bank, as staff second-guessed the new boss’s position on certain issues, in line with the then White House administration — climate change above all.

But under his leadership, the World Bank remained the largest multilateral financier of initiatives to adapt to or mitigate the consequences of climate change, investing a total $83bn over the past five years. It also more than doubled its commitment to the cause for the next five years as its 2021–2025 Climate Action Plan counts on $200bn. And it continues to play an important role in helping developing countries achieve their nationally determined contributions to reduce carbon emissions under the 2015 Paris Agreement.

As environmental, social and governance risks have grown in importance in capital markets, one highly successful tool that the World Bank helped to pioneer, more than a decade ago, is green bonds. Since the launch of its first green bond in 2008, the bank has issued the equivalent of about $15bn of such products. The institution is also looking to other sustainability aspects and has started to engage investors around some of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals, which cover areas from health to education and gender equality.

“This is a rapidly evolving field where we are quite interested in impact investing broadly,” says Mr Malpass. Further, the bank is engaged in fostering global public goods, helping countries to place an economic value on biodiversity, including forests, land and water resources, which would encourage better management of natural resources, while also helping assess how climate risks affect, for example, women and vulnerable people. “That [type of] conversation goes on daily — literally daily — within the bank,” says Mr Malpass.

Involving the private sector

Finally, there is another crucial issue in the future role of the World Bank and development finance in general. Experts and economists agree that multilaterals’ response to the crisis has exposed a disproportionate gap between the amount of development finance resources available, and the scale of the social and economic damage the pandemic has caused.

Mr Malpass emphasises the importance of the private sector to fill this gap. Starting from the World Bank’s emergency programme, which, he notes, involves all parts of the group: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, the original World Bank founded in 1944), which provides loans, advisory services and debt management products to middle-income, emerging market economies; the International Development Association (IDA), the bank’s concessionary lending arm for the world’s poorest and most vulnerable countries; and the group’s private sector lending and guarantee arms, the International Finance Corporation and the Multilateral International Guarantee Agency. “The private sector is something that needs to be part of what provides the resources and the jobs in the future,” he says.

Getting the US on board

But it is more than just the head of the institution that sets its course. The ambition and focus of the World Bank will likely be influenced by the new direction of its largest shareholder, the US. The administration of president-elect Joe Biden is set to take a diametrically opposed view to that of Mr Trump’s on several issues, most notably — and in line with the World Bank’s actions — on climate.

While Mr Trump regularly denied the existence of climate change, Mr Biden plans to invest $2tn in clean energy, “climate-smart” agriculture, electrical vehicles, sustainable homes and for the upgrade of four million buildings, so that US electricity production becomes carbon-free by 2035 and the whole country a net-zero emitter of carbon dioxide by 2050. Mr Biden’s approach is the antithesis of his predecessor’s when it comes to multilateralism too.

Scott Morris, a senior director at CGD, says: “I would expect a higher level of overall ambition from the Biden administration when it comes to the World Bank’s crisis response. I think they would be pushing the bank more aggressively to disperse funds, and they would be setting higher targets for financing commitments.”

This is in contrast with the scepticism expressed by outgoing US treasury secretary Steven Mnuchin at the World Bank and IMF annual meetings in October, when Mr Malpass asked donors to consider contributing a further $25bn for IDA countries. Such a request for IDA, or even a capital increase for the IBRD, could meet with “a more open-minded” response from the Biden administration, says Mr Morris. The World Bank last raised an additional $13bn in capital from members in 2018.

The private sector is something that needs to be part of what provides the resources and the jobs in the future

Talking to The Banker in November, while Mr Trump still refused to concede, Mr Malpass remained conventionally diplomatic about the issue: “I don’t want to anticipate what the political situation will be with our various shareholders. We listen carefully to the shareholders on their views of the direction for the bank … [But] I’m optimistic that there will be good support for the bank’s efforts, especially because we will remain very focused on delivering good products and doing it very quickly given the nature of the [Covid] crisis.”

The pandemic will unlikely be the only emergency at the horizon. Food insecurity, for example, remains an ongoing issue which became acute in 2020 with the worst desert locust outbreak of the past 70 years in east Africa and the Middle East. In May, the World Bank released a $500m programme to avoid famine in the region.

Homi Kharas, a senior director at research group Brookings Institute in Washington, says the World Bank “is doing as much as it can within the constraints applied by shareholders and their policies. But the problem is that both institutions, the World Bank and the IMF, have not been able to do enough.”

Additional help

The World Bank, the IMF and smaller multilateral institutions acknowledge they are unable to tackle development finance challenges on their own and estimate that the external financing needs of emerging markets arising from the crisis will likely be in the trillions of dollars and last for years.

New money will need to flow in developing economies, both domestically and from abroad — to make the new investments needed to strengthen health and education systems; transition to a greener economy; and ensure the required digital transformations are not let down by poor connectivity, so that countries have the right infrastructure for distance learning, for hospitals and health centres, and for better connected small businesses. And to prepare for other potential major external shocks.

As with other crises, not least the 2007–9 global financial meltdown, there is a likelihood of many developing countries pressing for more loans and, due to the nature of the engagement that comes with that money, of stronger ties with the World Bank. That could put the institution in a stronger, more influential position in the post-Covid period. Mr Morris wonders if this could lead to the World Bank, with more countries in its fold, having greater coordinating and convening power globally, or more of a leadership role on climate-related finance and preparing better for a possible next pandemic and other global external shocks.

Others need convincing. “What I see is [that Mr Malpass] is very focused on the work of the World Bank country teams, country by country. He’s been willing to roll up his sleeves and help work with [those] teams, and that’s positive,” says Masood Ahmed, president of the CGD, who previously worked at the World Bank and the IMF. “But I don’t think that the bank has taken on a leadership role on things like climate change and global public goods, alongside its work at the country level. I think that’s where more of a presence by the World Bank would be appreciated by many.”

Mr Malpass’s work for an institution that has a broader, sustainable impact on global economic and social development is not yet done.