Hands-on leadership: Venezuela's President Hugo Chavez has come under criticism for his involvement in the country's banking sector

A casual glance at Venezuela's banking sector would suggest that it is in good health. However, intervention from president Hugo Chavez's government is threatening the stability of the country's financial environment. Writer Brian Caplen

Venezuelan banks are labouring under a host of directives and controls that have left some of them short of capital and in poor condition to face any downturn in the economy.

Under the strictures of president Hugo Chavez's government, Venezuela's banks are obliged to direct nearly 50% of their lending to specified sectors; spreads are contained through a system of interest rate caps and savings rate floors and fees levels are controlled.

Given the challenges they face, the country's banks are faring well as they are noted for good management and risk control and an ability to work within a challenging system. But the question is how much further will the Chavez government go and what will be the extent of the pain?

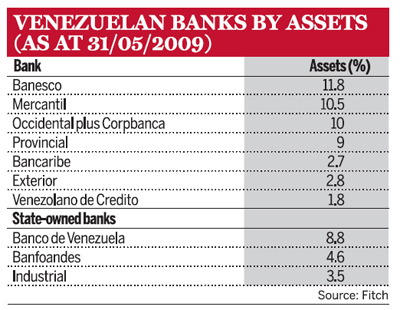

Rumours abound in Caracas that Banco Provincial, owned by Spain's BBVA, will follow its fellow national Santander into exile. Santander was obliged to sell its local bank, Banco de Venezuela, to the government following the news that it planned to sell the assets to private sector player Banco Occidental. The government objected to the deal and demanded to buy the bank. This brings the government share of banking assets to nearly 20% and has attracted speculation as to how much further the process might go. Will more Venezuelan banks be nationalised?

BBVA has vigorously denied that it plans to leave the country and has taken out advertisements in national newspapers to emphasise its commitment to Venezuela. But clearly in such an atmosphere speculation is rife about various possible outcomes.

A sorry state

Government officials meanwhile are known to privately lament Venezuela's poor credit rating when compared with other sovereigns with higher debt levels and a worse economic outlook. Yet there are reports of credit rating teams flying out from New York or London and then failing to get an audience with government economists. This inability to explain the Venezuelan story to the markets is bound to have repercussions.

Indeed, the administrative weakness in Venezuela is not the basic philosophy of the Chavez government that more resources should be concentrated on the poor, and that they should receive better education and health facilities. Most bankers and free market economists would support those outcomes. But where the populism of the Chavez variety falls down is, first, its determination to carry its anti-Western, anti-capitalist rhetoric into forums where it alienates the country and, second, the failure to establish a diversified economic base that fosters the energies and entrepreneurial abilities of ordinary Venezuelans so that they are no longer dependent on social programmes.

The country's current economic and social programme depends on oil prices staying high. With an official exchange rate that is three times higher than the black market rate, Venezuelan imports are being subsidised by the government's dollar earnings from the sale of oil. Such lavishness fuels an inflation rate of about 30% which hurts the poor, although controlled food prices alleviate them from the worst effects.

Pedro Palma, president of the Venezuelan National Academy of Economic Sciences, says that with the fall in oil prices and subsequent squeeze on revenues, the government supply of dollars at the official exchange rate has fallen from $188m a day last year to $89m a day in March and April of this year.

"Oil revenues have halved and this is forcing the government to restrict dollars. That is causing a shortage of dollars and is forcing importers into the 'free' [black] market." This further fuels inflation.

But Mr Palma says that Venezuela's productive sector cannot recover from its devastation from subsidised imports. At some stage, the social programmes themselves may come under threat from a worsening economic environment.

"We have to change our development strategy," he says. "The social programmes have allowed the poorest to improve but cannot solve poverty [in the long term]; this can only be done by promoting investment and creating jobs."

The danger is that as government revenues are squeezed, the adopted solution is to put even more pressure on the banks.

"We cannot completely rule out nationalisation, but in the case of Banco de Venezuela it seems more that the government saw an opportunity and took it," says Pedro El Khaouli, director of Fitch Ratings in Venezuela. "Banco de Venezuela was in negotiation with Occidental and when the government found out, it took the lead. Santander had been talking about selling for four to five years."

"There are a lot of rumours about BBVA but it has denied that it is thinking of selling. It says it plans to stay and I don't think the government is looking for more banks," says Mr El Khaouli.

Widespread control

The view of most analysts is that the government does not need to own more banks as it is effectively controlling the existing ones in the private sector through directives and regulation. The fear is, however, that an efficient bank such as Banco de Venezuela loses its edge under state ownership. Another state-owned bank, Banco Industrial de Venezuela, has recently been "intervened" by the government after running up losses totalling 190.7m bolivars ($88m).

The uncertainty impacts upon the entire system. Carlos Fiorillo, managing director of Fitch in Venezuela, says: "What limits the ratings of the Venezuelan banks is the various interventions by the government. A large part of the assets is government paper, there is considerable directed lending and in recent years the level of capitalisation has decreased as the assets have grown. Six to eight years ago Venezuela had the best capitalised banks in the region, now it has the worst."

The directed lending amounts to 47% of total loans - 21% directed to agriculture, 10% each to manufacturing and mortgages, and 3% each to microfinance and tourism.

But there are banks that can make these restrictions work. Raul Baltar, executive-president of Banco Exterior, says: "To survive in this environment we need to be as fit as possible, to be as lean as possible and to make processes as efficient as possible. We are one of the most efficient banks in Venezuela with a cost-to-income ratio of 42%."

One of the keys to Exterior's success has been in growing its deposit base through branch expansion, from 75 to 105 branches over the past couple of years, and operating the branches with just eight people whereas previously they had 12.

With margins restricted, effective deposit gathering is critical to success. "We have reduced the cost of deposits by extending the branch network and then, in addition, we have focused on the cross-selling of products," says Mr Baltar.

The bank has a strong corporate focus and its top 50 clients provide 30% of deposits. Non-performing loans (NPLs) are a low 0.85% with 300% coverage. The bank is not heavily involved in areas such as auto lending that can easily attract NPLs as growth slows.

Mr Balatar agrees with the analysts who think that the government is unlikely to acquire more banks. "With Banco do Venezuela it has a significant part of the system, it has a huge challenge in managing it all. There is enough activity in the country for the private and government banking sectors to co-exist."

Another bank which is able to use its network to good effect is Banco Occidental de Descuento, which has expanded following its acquisition of Corp Banca, a bank that has a good market share in the middle market.

Challenges to be met

But however good a bank's branch network and cost of deposits are, banking in Venezuela remains a challenge. As economic growth slows, despite a fiscal stimulus, there are fears that asset quality in the system will deteriorate and that capital ratios (equity to assets was 8.6% at the end of 2008) will be on the low side to fully meet the challenges.

"Current capital levels are considered low, given the inherent volatility of the economy," according to a Fitch report. There are several [smaller] banks that barely comply with local capital rules and others that are actually operating below such limits. The low overall reserve levels and limited upside for profits have highlighted the need for more conservative capital policies."

The Venezuelan environment clearly provides challenges for the banks. Most prefer to be apolitical and focus on doing their business and making a profit. So far, this has worked out well, but the outlook is uncertain to say the least.