Following a decade of the most intense regulatory onslaught in the history of banking, the Financial Stability Board has announced it is refocusing its attention – much to the relief of bankers. By Justin Pugsley

What is happening?

In a series of speeches in April and July, Dietrich Domanski, secretary-general of the Financial Stability Board (FSB), said the work of the body, which was mandated by the G20 to make the global financial system safer, is now transitioning away from policy-making towards “dynamic implementation”.

This means the FSB is going to be analysing the impact that global rules are having on banks and also assessing how they are being implemented. This may, for instance, mean greater attention on the peer reviews and assessments the FSB makes regarding individual financial centres.

However, the important point for bankers is that the days of spewing out new policy that financial institutions eventually have to implement are coming to an end. Although bankers cannot be entirely sure how individual jurisdictions will implement these policies in detail, they do at least now have a pretty good idea of what is in the pipeline over the next few years.

This neatly coincides with events at another very important policy making body: the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. In 2017, it said it was pivoting away from making new rules to focus more on the application and impact of existing rules.

Why is it happening?

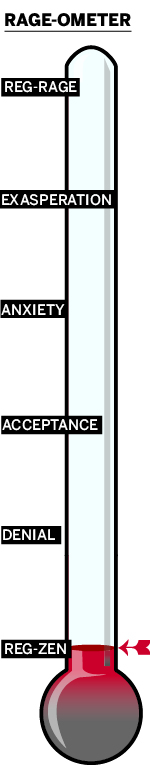

There are a couple of reasons. One is that regulatory fatigue has become deeply entrenched within the industry and national regulators. Another is that there is a feeling policy-makers have reasonably done as much as they can to prevent another financial crisis; it is just a case of tying up some loose ends here and there.

For instance, cyber-security is a major concern, there is a growing interest on incentivising good conduct within banks, and there is still a focus on individual areas – such as tweaking rules for over-the-counter derivatives, central counterparties and infrastructure finance.

Another factor is that political priorities have moved towards promoting economic growth and jobs, with less emphasis on financial stability. Some politicians blame the new banking rules for stifling credit availability to small businesses and the less well-off in society. They certainly will not welcome more tough rules.

The Trump administration in the US encapsulates that view very strongly – but in an age of populism, those views are to an extent echoed in Europe as well.

What do bankers say?

Bankers are relieved the era of making new rules is coming to an end. However, some see the fact that policy-makers’ focus is moving towards implementation and assessing consequences as an opportunity to lobby for favourable changes. They should not get their hopes up too much.

Regulators have a tendency to believe they have done a good job and many are quite proud of the slew of new rules they have produced over the past decade. For example, many global policy-makers deny that new rules have drained liquidity from capital markets or some sectors of the economy. If they do acknowledge this outcome, they simply say there was probably too much liquidity due to previous rules being overly lax.

Where banks may get a hearing is around some of the more technical areas where they can show with solid data that a subset of rules can be changed without undermining their ultimate purpose, whether that be financial stability or investor protection. But a significant reduction in capital requirements? Highly unlikely.

Will it provide incentives?

That is the $12,000bn question (a 2009 International Monetary Fund estimate of the cost of the financial crisis – but many put it much higher). Certainly, banks are much better capitalised and more attentive to risk. But there are still concerns: one being that banks tend to be heavily capitalised with government bonds of the country they are based in, potentially leaving them vulnerable to a deterioration in the creditworthiness of that country.

Another is the use of internal models, which promote capital efficiency. Some regulators believe these models underestimate risk, hence they have curbed their use.

But as the era of new rule-making appears to be wrapping up, new threats to bank profitability are rapidly emerging. These include cyber risks and, of course, there are now fintech and certain types of shadow banks conducting banking-type business with less burdensome rules. Even tech giants such as Amazon, Google and Apple are taking more interest in banking and could pose a real threat as they are established, well funded, customer-centric, efficient and largely liked by their customers.

The next phase in the transformation of banks towards nimble, digitally driven organisations could prove more challenging than complying with new regulatory frameworks.