Following the turmoil of recent months, a consensus seems to be building around tighter supervision of large regional banks in the US. Marie Kemplay reports.

What is happening?

The official post-mortem of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) does not make for an enjoyable read. Michael S Barr, vice-chair for supervision at the Federal Reserve, was tasked with conducting a rapid review of the bank’s failure, and the regulatory and supervisory circumstances surrounding it. And he does not hold back.

The harshest criticism is levelled at the bank’s own management, who fundamentally are to blame for its collapse, Mr Barr suggests, by failing “to manage basic interest rate and liquidity risk”, and its board, for failing to “oversee senior leadership and hold them accountable”.

But the report also found clear evidence of supervisory and regulatory weaknesses which contributed to SVB’s collapse. Mr Barr suggests the regulatory standards imposed on SVB were too low, supervision was not forceful enough, and the potential for its failure to generate systemic risks was not adequately assessed.

As a result, Mr Barr has proposed a raft of supervisory changes such as a re-evaluation of how supervision of banks intensifies in line with growth in size or complexity, and the possibility of higher liquidity and capital requirements being imposed where weaknesses are identified in banks’ risk management and governance.

The report also suggests several regulatory changes such as revisiting the Fed’s tailoring framework (its system for assigning bank regulatory requirements based on the level of risk they are judged to pose) particularly for banks with $100bn or more in assets, and reviewing its requirements around interest rate risk, liquidity risk – starting with the risks of uninsured deposits – and capital levels.

Why is it happening?

The speed at which SVB collapsed took the industry and regulators alike by surprise. For all its subsequently much-scrutinised shortcomings, prior to March 2023 few would have predicted it falling apart so completely. Wider market jitters and the events at First Republic Bank that followed SVB have also kept these issues in the headlines.

In the weeks that followed SVB’s collapse, regulators were keen to stress the fundamentally sound nature of the US banking system and to suggest that problems faced by the likes of SVB were of their own making. However, it is hard to explain away the collapse of three sizeable banks within the space of two months. The mood music generated by those events means that some action needs to be seen to be taken.

Mr Biden repeated his calls for regulators to take action in the wake of First Republic’s takeover by JPMorgan.

US president Joe Biden has also weighed in on the debate over regulatory action by calling for changes made during the Trump administration, which watered down the supervision of large regional banks, to be reversed. To this end, the White House pointed to a piece of Yale analysis which suggests SVB’s liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) as of the end of 2022 stood at 75% (a proxy for its likely situation in March 2023). This is significantly below the 100% minimum LCR threshold that would have applied to SVB had the rules not been changed to remove LCR and other requirements from the supervision of SVB and other similarly sized banks.

Mr Biden repeated his calls for regulators to take action in the wake of First Republic’s takeover by JPMorgan.

What do the bankers say?

At this stage, no one is really raising their head above the parapet to argue against these changes, although it is worth remembering that most of what has been suggested so far will not affect the US’s largest banks, which are already subject to enhanced prudential regulation and supervision.

Will it provide the incentives?

Much of what has been proposed can be implemented within the existing legislative framework, meaning no new laws will need to be passed, so it seems likely at least some of these changes will come into force, and reasonably quickly.

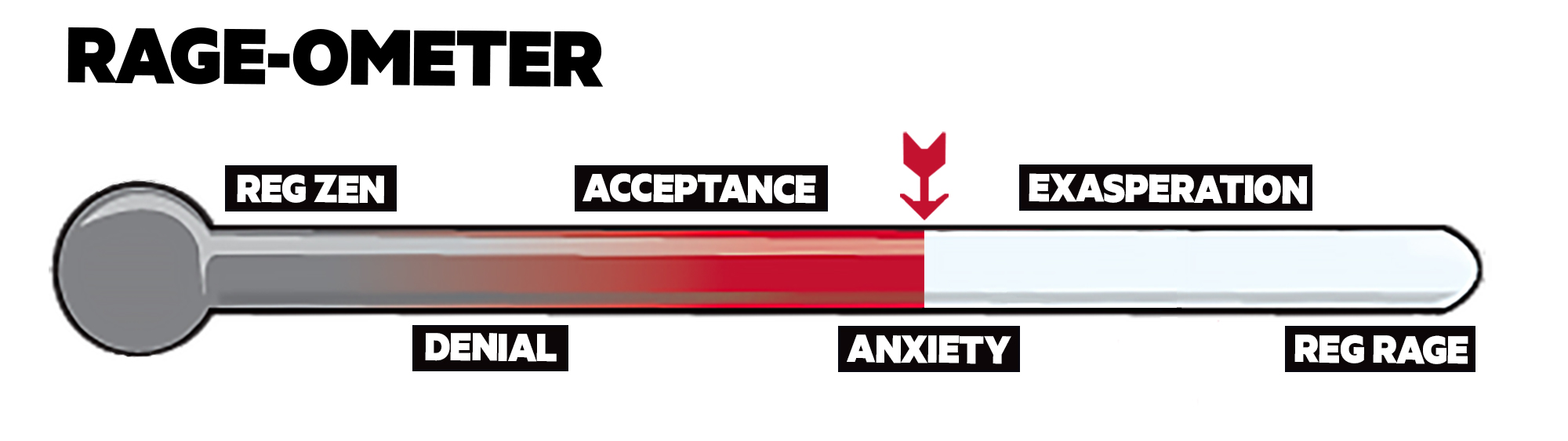

But the jury is out on whether these kinds of safeguards would have completely prevented recent events. A trickier issue to get right, and one which Mr Barr refers to explicitly in his report, is creating a culture and approach to banking supervision which “empowers supervisors to act in the face of uncertainty”. After more than a decade of relative stability in banking performance, he suggests that bankers may have become over-confident and supervisors too accepting.