Danièle Nouy, secretary-general of the Banque de France's Banking Commission

Distinguishing between banks' funds and shareholders' equity has become increasingly difficult as the rise of hybrid capital instruments has introduced grey areas to the financial sector. Writer Charles Piggott

Complexity in financial markets has made it increasingly hard to identify what constitutes capital. For example, shares including guaranteed dividend payments or bonds allowing issuers to waive coupon payments, or even write down principal against losses, are neither truly shareholders' equity nor debt.

Hybrid capital instruments such as these, part bond and part share, have been around for more than a decade. While they have successfully lowered banks' funding and tax costs, they have also created a growing headache for regulators struggling with one of the largest grey areas in banking. In the wake of the financial crisis, defining: 'what is capital' has become a trillion-dollar question, since it hangs on not just the future size and profitability of the banking sector, but also who bears the brunt of bank losses. Each country has its own variations, but it is broadly acknowledged that the highest form of bank capital (Tier 1) must have the following qualities to be included as regulatory capital:

- the ability to absorb losses;

- permanence (it does not have to be paid back); and

- flexibility of payments to shareholders.

Unclear delineation

Steven Roith, capital markets partner at international law firm Clifford Chance in London, says the "bright white line" delineating banks' own funds has long since been replaced by a grey scale from common shares (the purest form of capital) down to highly subordinated debt, which behaves like capital only during insolvency.

Although calls for greater clarity on loss absorbency of different tiers of hybrid capital grew loud as private investors and governments faced mounting bank losses during the crisis, the issue has haunted regulators ever since a hastily drafted press release from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in 1998. This release, which came to be known as the 'Sydney release', gave guidelines for national regulators on hybrid capital and allowed banks to include a percentage of hybrid instruments as Tier 1 capital.

Danièle Nouy, secretary-general of the Banque de France's Banking Commission, says: "As early as 1998, the Basel Committee raised the issue and decided to limit instruments with incentives to redeem to 15% of total Tier 1 capital (the so-called 'innovative' instruments) while requiring that the predominant part of Tier 1 comprise voting common equity and disclosed reserves. This has been interpreted, in some countries, that the total amount of hybrids, be they with or without incentives, could represent up to 50% of Tier 1."

Many regulators are uncomfortable with the inclusion of hybrid debt as the highest form of capital. Nearly two years ago, the UK's Financial Services Authority (FSA) published a discussion paper entitled Definition of Capital, which said: "Creating more sub-tiers of capital has arguably undermined the essential character of regulatory capital." It also acknowledged that the inclusion of innovative forms of capital in the highest tier had confused the central rationale for Tier 1. "Although there is a widespread consensus that the essential purpose of Tier 1 is to absorb unexpected losses, there is no agreed consensus that all the instruments that are now permitted to be included in Tier 1 unambiguously achieve this. The most urgent matter to agree is a consensus on how loss absorbency is achieved in practice."

JPMorgan's co-head of debt capital markets in London, David Marks, says: "This is not a new debate and it will not disappear in the next 20 months. Although Anglo-Saxon preference shares predate the Sydney press release, the hybrid asset class was in many ways born out of the BIS's 1998 release."

One of the biggest problems with the increasing complexity of banks' capital structures is that it has become virtually impossible to make realistic comparisons of banks' financial strength across national boundaries. Back in 1989, The Banker wrote: "There has been some improvement in international capital standards, but disclosure regulations in different countries are still a problem." Regional variations on what banks can include as Tier 1 capital have made it almost impossible to use Tier 1 as a benchmark to compare banks on a like-for-like basis across national boundaries. In The Banker's 1990 ranking of banks, "such hybrid instruments as cumulative or fixed-term stock" were excluded on the basis that "only by adopting such a policy can The Banker attempt to make international comparisons among the world's financial giants."

Bedevilled in detail

Although the BIS's original 1988 guidelines have been periodically updated, rule-based interpretations at the national level have become particularly complex as regulators struggled to keep pace with financial innovation. The Sydney press release left national regulators in charge of deciding which hybrid instruments could be included as Tier 1. "Hybrid capital instruments vary considerably, depending on the jurisdiction in which they are issued, mainly because of the variety of legal and tax systems," says Ms Nouy.

In the UK, for example, the FSA has used at least seven sub-tiers to grade the quality of bank capital and its main guidelines on capital include nearly 300 rules and six annexes. "The market is very imaginative," says Ms Nouy.

In the disputes that have followed the crisis, some argue that the only instruments that truly meet each of three key tests of what constitutes capital are common shares. Ms Nouy says that bank supervisors are under huge pressure and scrutiny now and she believes that a return to common shares would restore confidence in the banking sector and create a level playing field. Commenting on Basel's latest press release calling for the predominant part of banks' Tier 1 capital to be made up of common shares and retained earnings, she says: "Banks will not be able to issue anything other than common shares. This statement makes the rules clear, simple and identical for all."

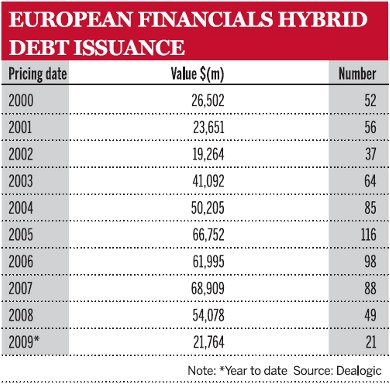

However, many in the markets believe that hybrid issues will continue to play an important role in helping banks to recapitalise after the crisis. According to Barclays Capital, between July 2008 and July 2009, less than $70bn-worth of ordinary equity capital was raised by European banks from public markets. By comparison, some $100bn-worth of hybrid Tier 1 securities were raised from European governments and an additional $30bn in hybrid Tier 1 securities from the capital markets. In total, European banks had issued $352bn-worth of hybrid Tier 1 securities as of July 2009. In recent months, many large European banks have issued large Tier 1 hybrid securities.

As part of the government recapitalisation programmes, many European regulators raised the ceiling for the level of hybrid capital allowed as Tier 1. JPMorgan's Mr Marks believes that due to the quantums of money involved, banks will struggle to replace government capital - the majority issued in the form of hybrid capital - with anything but similarly structured deals.

At the same time, many within the regulatory community want to see banks reduce reliance on hybrid capital. "The crisis showed that this is not sustainable: the complexity and diversity of capital instruments have shed doubt and concern as to the real quality of banks' capital and then to their financial soundness," says Ms Nouy.

One problem with lower forms of capital, such as subordinated debt, is that they only meet the criteria of capital once a bank has become insolvent. Before 2008, most hybrid instruments had been untested in a loss-making environment and weaknesses in the mechanisms used to decide between 'going-concern' capital and 'gone-concern' capital, particularly once a government has stepped in with public funding, are only now coming to light.

David Marks, JPMorgan's co-head of debt capital markets in London

A way forward

Ms Nouy believes that banks have so far been reluctant to trigger loss-absorbing mechanisms on hybrid capital securities for fear of damaging their credibility with investors who expect to be treated in the same way as vanilla bond holders, receiving automatic and certain coupons on each payment date.

Ms Nouy believes that this situation will have to change. "In Europe, new rules have just been introduced to ensure that hybrid capital is more effective in the future at absorbing bank losses on a 'going-concern' basis. In particular, it is now explicitly required that appropriate mechanisms be in place to allow for the principal, unpaid interest or dividend of the instruments to absorb losses and not hinder the recapitalisation of the credit institution," she says.

The resulting investor losses on hybrid securities will make it more expensive for banks to use them as a form of high-ranking capital. Commenting on the latest consultation paper from the Committee of European Banking Supervisors, Upendra Choudhary, a chartered financial analyst at Frontline Analysts, says: "We believe the most adverse change for investors is the proposal for loss absorption on a going-concern basis through principal writedowns or conversion to common equity."

Investors are already seeking legal clarification on loss absorption mechanisms embedded in hybrid capital securities. In theory, Tier 2 capital only protects depositors and senior creditors after default. "In terms of loss absorption, this means [Tier 1] hybrid investors should not be able to sue for bankruptcy," says Mr Choudhary. He adds that a second "more contentious" idea is that hybrids should not hinder the recapitalisation of a distressed firm.

"This came to the fore during the credit crisis, where the preferential rights of hybrids to principal repayments undermined the ability of governments to raise fresh equity in troubled banks. This led to some ad-hoc action to write down hybrid principal - for example, at the UK's Bradford & Bingley - and a general consensus among regulators that, in future, hybrids at distressed firms should suffer more burden-sharing in line with equity," says Mr Choudhary.

In August this year, the UK's Northern Rock deferred coupon payments on some of its hybrid debt on the basis that its capital had fallen below minimum requirements. BayernLB of Germany and nationalised Irish lender Anglo Irish Bank have also both deferred interest payments on hybrid Tier 1 debt.

Other examples of loss absorption by hybrid capital securities include the UK's West Bromwich Building Society's exchange of lower Tier 2 securities into core Tier 1 profit-participating deferred shares and Spain's Banco Popular's announcement that it would not pay coupons on non-cumulative preferred securities and instead offer to exchange them into common equity.

Georg Grodzki, L&G head of credit research

Investor fears

Earlier this year, L&G Investment Management, which holds significant investments in both Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley, wrote an open memorandum to the UK parliament calling for greater clarity on hybrid capital and loss absorbency. "Under the future solvency rules, coupon payments on Tier 1 instruments are likely to become much more discretionary and subject to regulatory intervention. This heightened degree of payment uncertainty should be clearly spelled out in the documents and reflected in the pricing, placement and ratings, if any, of such instruments," says L&G head of credit research Georg Grodzki.

Mr Grodzki agrees that regulators are moving towards a more purist definition of equity. "As a major investor in bank debt and capital instruments, we welcome the return to strict and basic principles on the part of regulators," he says.

Many in the financial markets have already abandoned the existing 1988 guidelines on capital adequacy to focus on common equity as a guide to bank strength. JPMorgan's Mr Marks says: "Investors ask: what is a bank's core Tier 1, or what is a bank's leverage ratio, they don't ask what a bank's capital adequacy ratio is any more." He adds that this shift has come through bitter experience during the past two years. "The [BIS] total capital ratio is now pretty much ignored. Since systemically important banks tend not to go bust, their Tier 2 'gone-concern' capital is less relevant than their Tier 1 or core Tier 1," he says.

However, Mr Marks also believes that regulators may have undervalued the extent to which lower-tier capital absorbed bank losses during the crisis. He recalls a rating analyst who was "almost lynched" at an industry conference in London during the height of the crisis for telling an audience of investors that rating agencies were surprised at the low degree of loss participation associated with hybrid capital. "Fixed-income investors holding paper that had been marked down by 70% certainly felt like they had participated in banks' losses. These were shocking losses and a cathartic event for investors," he says.

Steven Roith, capital markets partner, Clifford Chance

Brought to a head

Even so, during the worst of the crisis, many, including the US government, used much tougher definitions of capital, which excluded hybrid instruments, to gauge banks' real financial strength. The US stress tests, for example, ignored hybrid Tier 1 capital and lower Tier 2 capital, instead focusing solely on 'tangible common equity'.

George French, deputy-director of bank supervision policy at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in the US, says recent events clearly validated the long-held view in US regulatory circles that common equity should be the "predominant" component of capital. "This was re-emphasised in the US stress tests," he says. "Certain hybrid securities have been allowed Tier 1 capital status for US bank holding companies (but not for insured banks), but consistent with their nature as debt instruments, these securities do not provide the same level of capital support as common equity or other non-debt capital."

Many now think that European regulators will also adopt a more orthodox definition of capital, based on common equity and retained earnings. In their statement following the G-20 summit in Pittsburgh, world leaders supported the introduction of a new, "internationally harmonised leverage ratio" similar to that used in the US. By the end of this year, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision will publish proposals to replace the arcane 1988 guidelines, which were themselves hastily drafted in reaction to solvency problems in the US and Japan.

"There is now huge pressure on regulators to change the rules which so clearly failed to prevent the recent crisis," says Clifford Chance's Mr Roith. "The changes will dwarf previous revisions and change the way banks capitalise themselves." But he warns that this could affect European banks more than their US counterparts due to heavier regulatory restrictions on issuing new shares, particularly in countries such as the UK.

CoCo bonds taste test

Lloyds Banking Group's announcement on November 3 that it would issue a form of hybrid capital known as contingent convertible bonds - or CoCo bonds - as part of its recapitalisation of about £21bn ($34.9bn), has brought what was, until now, a relatively obscure asset class into mainstream use.

Lloyds intends to exchange about £7.5bn in preference shares and other subordinated securities into enhanced capital notes (ECNs), which will convert into shares if its Tier 1 capital falls below 5%. The hybrid capital issue, part of a recapitalisation plan to lift Lloyds' core Tier 1 capital ratio from 6.3% to 8.6%, has been structured to avoid upsetting EU authorities which have become increasingly vocal in their objection to hybrid coupon payments by banks supported by government capital.

One commentator said that Lloyds has used the European Commission's objection to coupon payments by state-aided banks as "a lever" to force existing holders of preference shares to switch into new riskier but higher-yielding securities, rather than losing income on existing preference shares.

Lloyds ECNs will qualify as lower Tier 2 capital, the same as the existing 58 securities it is offering to replace. However, the bonds' new feature allows for conversion into ordinary shares if the group's Tier 1 capital falls below 5%. Investors have so far been less than warm in their initial appraisal of CoCo bonds. Unlike traditional convertible bonds, which offer upside rewards and downside protection, Lloyds CoCo bonds only convert into equity if the bank runs into trouble.

L&G Investment Management's head of credit research, Georg Grodzki, admits that the trigger mechanism involved in the Lloyds exchange offer is "reasonably transparent, assuming consistency and stability of accounting and solvency rules over time". However, as an investor, he says that he is not overly enthusiastic about this new class of instruments.

Mr Grodzki sees the loss potential on CoCo bonds as both severe and potentially very sudden. "We do not think they should be a core holding for investment-grade bond funds and they should be excluded from mainstream investment-grade indices." The bonds have been rated BB (below investment grade) by Fitch.

Once the dust settles on the Lloyds deal, however, investors may benefit from some of the more positive attributes of this new asset class. For example, coupon payments on Lloyds CoCo bonds will fall outside existing European Commission rulings and the bonds also carry a final maturity date, adding a certain amount of comfort for fixed-income investors.

Another benefit of the new class of instrument over previous hybrid bonds is that the trigger mechanism is comparatively simple and transparent, which may ease investor and regulatory uncertainty over hybrid capital structures. Recent government bail-out packages raised questions over when the equity features embedded in hybrid capital instruments should be triggered. Banks faced a difficult choice of whether to defer or cancel coupons or continue making discretionary payments even after government support.

CoCo bonds may carry risks, but they could also offer banks a way of boosting total capital levels without paying the full premium demanded for pure equity. European banks will be watching closely to see whether investors complain about a bitter aftertaste of the new CoCo Bonds.