Widely criticised after the subprime crisis as part of the problem, it seems that credit ratings agencies are still regarded as part of the solution by the market and regulators alike. Writer Philip Alexander

Since a wave of downgrades on subprime residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) began in mid-2007, sometimes from high investment grade to low speculative grade, credit ratings agencies have been in the eye of a storm. Regulators have placed them under increased scrutiny, investors have challenged both existing ratings methodologies, and changes made to those methodologies, at least one lawsuit alleging fraud by the agencies has been allowed to proceed in the US, and the state of California is also examining whether to subpoena the agencies.

The regulatory changes are profound. The new rules enacted by the European Commission and US Treasury effectively ensure that agencies will become fully supervised entities, with the potential to lose their licence in the event of serious misconduct. The Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR) will be responsible for monitoring performance under the EU legislation, with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) playing the supervisory role in the US.

"The new regime will require all existing credit rating agencies that want to remain in business to apply for registration between six and nine months from the regulation's entry into effect," says Karl-Burkhard Caspari, the German chair of CESR's expert group on credit rating agencies.

"This represents a fundamental change for us - not only will we now be subject to ongoing oversight and inspections, we will also be subject to severe regulatory penalties if we breach the rules," says Martin Winn, a spokesman for Standard & Poor's (S&P).

The three main agencies, S&P, Moody's and Fitch, have been obliged to create new oversight committees and roles such as chief compliance officers or chief criteria officers. These officials are intended to set overall ratings methodology, allowing analysts to concentrate on processing individual ratings and ensuring that methodology is devised at one remove from bankers representing the issuers.

At least one investor believes this development is not necessarily beneficial, because the oversight committees are too far removed from the market to have a sufficient grasp of structured credit products.

However, Jeremy Carter, senior director in the structured credit ratings team at Fitch, has confidence in the three-man screening panels the agency has created to examine new ratings requests, which include a managing director from an independent analytical team. "You need an expert to analyse the details. But if you are asking someone at a high level if this transaction makes sense - who is the counterparty, what is their motivation, what are the underlying assets, are there any dependencies - if something does not smell right, then it probably should not be an AAA rating," he says.

New ratings methods

In practice, ratings for plain vanilla debt instruments issued by companies and governments have attracted little complaint during the crisis, and retain the faith of investors. In addition, says Steven Hall, principal advisor on financial risk management at KPMG in London, the credit rating agencies have several decades of data on corporate bond defaults that can be used to support the calibration and testing of their own and banks' internal ratings processes.

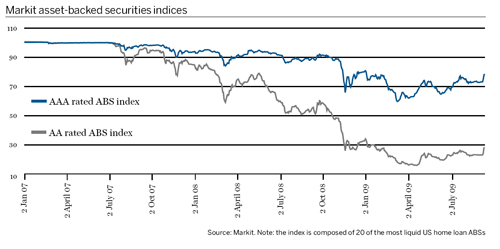

By contrast, the structures and underlying collateral of asset-backed securities (ABS) have changed constantly, especially in the past few years, making it difficult to compile comparable historical trends. When banks began securitising mortgages extended to subprime borrowers in the US, the performance of the resulting RMBS was quite different from previous securitisations. An extra level of correlation risk was added by creating collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) referencing these RMBS.

As a result, there have been widespread methodology changes across structured credit, not only for subprime-related securities, but also for ABS and CDOs referencing leveraged loans, small-business loan portfolios, commercial mortgages and consumer or auto loans.

At least one agency, Fitch, was prepared to sacrifice potential new business by placing a moratorium on new ratings in each asset class while it undertook this review. This decision avoided the potential embarrassment that other agencies faced when they heavily downgraded programmes just months after rating them, even though the performance of the underlying collateral had not changed.

Perhaps most promising, the agencies are showing willingness to cap or even turn down new ratings if they have concerns about the structure. Mr Carter says Fitch screening committees have turned down ratings where "data is not acceptable or not sufficient or where there is too much dependence on a single counterparty".

Frederic Drevon, managing director of the European structured finance group at Moody's, says the agency is now more conservative granting top ratings to CDO products with embedded market-value triggers. The sharp increase in market volatility since the financial crisis has forced some of these structures into technical default, and Mr Drevon says it is difficult to compile the kind of reliable forward-looking data on market values that the agency now wants to build into its ratings models.

However, there are concerns over what one investor calls "trying to backsolve models to ensure that AAA ratings would have been maintained over what has been the worst credit cycle in 80 years", rather than downgrades due to specific underperformance by collateral.

Oliver Burgel, who is responsible for structuring and fund analysis at CDO manager Babson Capital Europe, is frustrated at heavy downgrades in the corporate collateralised loan obligation (CLO) sector, where the underlying collateral - corporate leveraged loans - is a relatively long-established asset class, even if the CLO structure itself only goes back a decade.

"CLOs are behaving exactly as they are supposed to behave as the stresses flow through them. Realised losses are still quite low, not even near the equity tranche base-case level for funds that are four or five years old. So why the sledgehammer treatment?" he asks.

The combination of errors on original ratings and overcompensation in the methodological response has profoundly changed the view of Michael Fryszman, head of ABS investments at AXA Investment Managers, which is one of the largest structured finance investors with about €40bn in structured assets under management.

"If the rating process is transparent with good information around it, then ratings agencies are very useful. But if not, the rating itself becomes another risk that we must analyse when investing in a transaction, because the rating can crystallise price action if there are surprises," says Mr Fryszman.

Entrenched role

This unprecedented wave of criticism and the heavy investment in in-house analytical resources by institutional investors and fund managers might cast doubt on the future business model of the ratings agencies.

For the banks themselves, pressure from investors and regulators alike means the process of measuring current credit risk is only the starting point for capital management. "Whether the credit risks are measured by internal models or by credit ratings, the banks are being asked much more than before the crisis to apply stress-testing to ensure the cushion of capital they hold is adequate in foreseeable circumstances," says Richard Barfield, a director of the risk and capital advisory practice at PricewaterhouseCoopers in London.

Some of the largest investors in securitisations, especially in Europe, were structured investment vehicles (SIVs) and off-balance-sheet conduits of the banks themselves. These invested in AAA tranches of long-dated ABSs, and leveraged up by funding themselves in the very short-dated commercial paper markets. The process of asset selection was mechanical and yield-seeking, without extensive credit analysis of the individual securitisations.

The SIV sector has all but collapsed, taking with it the major source of ratings-driven investment in structured credit. "In Europe, it appears that about 50% of the ABS investor base was made of arbitrage conduits, SIVs or banks, and this has disappeared. Securitisation was seen as a disguised way for some banks to increase leverage without regulatory scrutiny. The challenge was more to source assets than to find investors and put savings or pensions to work to provide liquidity - now of course this has reversed," says Marc Nocart, global co-head of securitisation at Société Générale Corporate and Investment Bank.

The remaining investor base is much more sophisticated - mostly pension funds, insurers or their outsourced fund managers, plus banks themselves - and had placed little reliance on credit ratings in the first place.

"Structures are less complex, with more recourse to the originator, and investors are not viewing ratings like before. They are regarding ratings as a tool, but not as a currency," says Michael Millette, head of investment banking structured finance at Goldman Sachs in New York.

Unrated issues

In this context, Credit Suisse launched a $1.2bn RMBS in July 2009, backed by a portfolio from American General, the consumer lending arm of AIG, without the benefit of credit ratings. Credit Suisse formed a partnership to participate in the RMBS servicing vehicle, to allay investor fears about inadequate servicing of collateral. Given uncertainty about ratings methodology and accuracy at present, this was a more practical measure to win over investors.

"Investors were not precluded from participating by the absence of ratings, and having gone through the crisis, they are more confident about their own measures of risk," says Ben Aitkenhead, co-head of structured products at Credit Suisse in New York.

However, he adds that regulatory capital measurements are still at least partly driven by ratings, while pension funds may set minimum or weighted-average ratings requirements for their money managers. "If the transaction had been rated, more investors would be able to purchase the deal, and the lower yield that could have resulted would have been not immaterial," says Mr Aitkenhead. Ratings still appear to make economic sense for issuers.

They are also still embedded in regulatory use. Although more sophisticated banks can use the internal-ratings based (IRB) approach to measure regulatory capital for plain vanilla debt, they are obliged under Basel II to use external credit ratings to calculate capital requirements on holdings of securitised products, says Mr Hall at KPMG.

A US Treasury paper from July 2009 requested the President's Working Group on financial markets to "determine where references to ratings can be removed from regulations". However, regulators themselves are likely to continue making some use of credit ratings to cross-check their own calculations or the internal models of the banks.

"A common acceptance of credit ratings across supervisors gives comfort to a regulator in the UK or Germany that regulators in the likes of Latvia or Iceland are applying the same standards, even though the Latvian or Icelandic regulator is inevitably smaller and less well resourced," says Richard Everett, partner at law firm Lawrence Graham who was previously an in-house counsel for the UK's Financial Services Authority.

In fact, the rescue efforts for the financial system over the past year have, if anything, entrenched credit ratings further. Ratings from two agencies are needed to make securities eligible for the US Term Asset-Backed Loan Facility (TALF), which allows investors to borrow up to five-year money via the Federal Reserve, collateralised by newly originated ABSs of consumer or small business loans. The European Central Bank (ECB) repo window requires one rating on securities posted as collateral.

Valuations beyond ratings

To meet increased regulatory scrutiny, including the new mark-to-market accounting regulations in Europe and the US, banks and institutional investors are turning to a mushrooming industry of analytical firms that look well beyond the credit ratings.

Andrew Davidson is the CEO of an eponymous analysis company that he founded in 1992, and the firm has in the past four years intensified its capabilities to analyse ABS credit risk. "If ratings are assigned through the cycle, that is not the way to manage your risk on a daily basis, but it might be the basis for regulatory guidelines. You want some stability in portfolio holdings, but you also need to be able to measure the changes in risk on that portfolio on an ongoing basis," says Mr Davidson.

In fact, the groups owning the three leading ratings agencies have become some of the leading players in the field, effectively providing the parent company with a diversifier against declines in deal revenues and increased compliance costs for the ratings businesses.

S&P's has expanded its evaluated pricing service, which has existed for many years, to include a Valuations Scenario Services team founded in 2009, and also has a consultancy called Risk Solutions. Fitch established Fitch Solutions in early 2008. Moody's bought Wall Street Analytics in December 2006 and Belgian firm Fermat in late 2008, and is now consolidating them under the brand name Moody's Analytics.

Peter Jones, the head of Valuations Scenario Services at S&P, says this team fits with the change in regulatory attitudes towards stress-testing credit portfolio performance, rather than relying on a single set of assumptions to analyse the portfolio. "A 5% difference in the loss assumption on underlying collateral can equate to a 40% or 50% valuation hit on a given tranche of a mortgage securitisation," says Mr Jones.

Conflict of interest

These advisory and valuations units are legally or operationally separate from the ratings agencies. But competitors are concerned how much they appear to be trading off the entrenched market position of the ratings businesses.

"If you want to have a firewall, why not put a different brand name on the valuations business? We think we are good at what we are doing because we are totally independent, we don't have any assets under management, we don't have a brokerage arm, we just focus on providing advisory services," says Zeshan Ashiq, a former structured credit analyst for monoline insurer Financial Security Assurance, who founded his own advisory firm, Shooters Hill Capital, in 2008.

And regulators are asking the same questions, concerned that advice given to originators by the subsidiaries of companies that own ratings agencies could potentially help structurers to game the system in terms of the ratings themselves. A CESR report in May 2008 noted that "credit rating agencies have not properly segregated or disclosed all services that pose a conflict of interest to their rating services".

In particular, there is some cross-selling of ratings business products to advisory clients, including the structuring teams of investment banks. For example, Moody's Analytics sells a suite of products called CDONet, which includes the cashflow models used by Moody's structured finance ratings analysts. Investment bank structuring teams use these products to simulate the effects of changes in structure on the ratings for a potential transaction.

However, Gus Harris, executive director of structured finance for Moody's Analytics in New York, believes this approach is positive for market transparency. "Moody's embraces more users of these models because it adds information and transparency to the market place. Some of the model assumptions are available through our research services as well," says Mr Harris.

And many investors appear to sympathise with this view, arguing that greater clarity on how ratings would perform given particular changes in input assumptions would make them more useful and reduce the potential for market disruptions.

The consensus appears to be that, if the ratings are adequately reflecting credit risk, then changing structures to enhance the ratings also makes the transaction more creditworthy. This is especially relevant to the burgeoning re-securitisation market - about $30bn in securitisations that had been downgraded below investment grade were repackaged, with a new subordinated tranche to allow the senior tranches to return to investment grade.

Credit Suisse has participated in about 25% of these transactions, and Mr Aitkenhead says they suggest there is a growing convergence between ratings agency criteria and investor expectations. "An investor might say they want a particular credit rating and 30% credit support, but if you can get them the rating with only 25% credit support, they will still want 30% to buy the deal," says Mr Aitkenhead.

But market participants are still wary of whether the safeguards are in place to ensure that ratings processes remain rigorous even when memories of the crisis begin to recede. What has historically been lacking from the ratings business is the genuine competition that would pressure each agency to maintain its analytical quality.

"We only have three agencies, and in most cases two ratings are required. It is a market that has virtually no competition, and the agencies have been able to retain secrecy around their models," says Francesco Fraterrigo, head of credit treasury at HypoVereinsbank.

The US has already begun granting long-standing ratings agencies official recognition for use in bank supervision, including insurance specialist AM Best, and RealPoint, which focuses on real-estate backed assets. In October 2008, the Russian central bank also recognised some local ratings agencies. CESR is also looking to expand the number of fully licensed agencies across the EU.

Level playing field

Alongside this, market participants will need access to comprehensive and comparable data from all licensed agencies, to choose which they trust. The ECB apparently compiles such data already to monitor the ratings accuracy on €800bn in assets it is holding as repo collateral. But it is not the official regulator for ratings agencies in Europe, so it does not disclose these studies.

CESR is proposing a public equivalent, a central repository of ratings data. "The purpose is to assist investors to draw performance comparisons between different rating agencies. It would allow, for example, any investor to know the number of ratings done in each rating category, the average default rate for different instruments having a specific rating, and the number of up- and downgrades in the specific sectors," says Mr Caspari.

Investors are enthusiastic. Daniel Riediker, managing partner of structured credit investor Alegra Capital Partners, says it would be particularly helpful for investors to be able to track any differences in rating volatility between corporate and structured credit at the same ratings level.

And the agencies are supportive. "We have historically invested in providing tools for investors to understand the performance of our ratings - by region, asset class, maturities - so we are completely open to the market understanding the performance of our ratings and coming to their own views," says Mr Drevon at Moody's.