Banks are reticent to discuss the consequences of the US's new Volcker Rule, restricting proprietary trading. While some analysts predict dire results for market liquidity, others suggest that bank leaders privately welcome the opportunity to pull out of risky prop-trading activities. Writer Silvia Pavoni

The US Volcker Rule provisions, incorporated in the Dodd-Frank Act, have generated furore among investment banks over the future of their proprietary trading activities. Some operations are being shut down and others restructured, but there is still uncertainty as to which activities will be affected.

First proposed more than a year ago, many questions were still left unanswered when the Volcker Rule was passed into law in July 2010. Many points are still unclear, while the text of the bill is being refined before becoming effective at different stages. The Financial Stability Oversight Council, a body of regulators chaired by the US treasury secretary, has until January 22 to decide how to implement the Volcker Rule.

Hoping to report on what strategies banks are adopting to deal with the possible outcomes of the Volcker Rule, or at least what their mood is currently, The Banker contacted various international banks and all major US investment banks, all of which would be affected by these changes - the most radical regulatory shift since the introduction of the US Banking Act in 1933 in response to the 1929 financial crash and the Great Depression.

Only Goldman Sachs put forward a spokesperson. The other banks either declined to comment, offered mildly related pieces of research on the subject, or simply did not respond to our interview requests. In one case, a bank said that it was not going to talk, it had no research on the topic and that even if it did, it would not share it with us. This, at least, tells us that the mood is tense.

The Volcker Rule prohibits banks that are subject to the US Banking Act from trading with the bank's own money unless such activities are related to market-making. In addition, the regulation prohibits investing in hedge funds and private equity firms outside of certain restrictions, which include the dilution of the bank's interest in the funds after one year and that total interests in such funds do not exceed 3% of the bank's Tier 1 capital.

The problem is that money-making activities often require holding clients' positions for some time while the best price for that order is found. Many bankers fear that the regulation will end up creating dangerous restrictions to such market-making activities, as a clear definition of what the Volcker Rule would regard as proprietary trading still has to be determined.

If a client wants a bank to make markets in risky and illiquid assets, the bank cannot avoid using its own capital to trade in those assets. But when does it stop being market-making and become proprietary trading?

"Until [things] settle down, which will take a while because the Dodd-Frank Act will require a lot of write-out in terms of details, there is a danger that people will become very risk-averse and therefore the end-users, corporates or blocks of retail customers will end up with a suboptimal solution in hedging their risk," says Giles Williams, partner in the regulatory services practice at KPMG.

But while nobody likes uncertainty, the industry is even more worried about a clear but overly limiting final outcome of the legislation. A too-prescriptive definition, for example, could end up eliminating the liquidity that proprietary trading creates for market-making activities. At the same time, if the law is in the form of strict rules rather than principles, there may be loopholes and banks are expected to find ways around the prohibitions.

"Proprietary trading activities play an important role in providing market liquidity," says Todd Groome, chairman of the Alternative Investment Management Association. "I believe there are people in the [US] Federal Reserve who are thinking about that and may have some of their own reservations on what would happen in banks where proprietary trading may also play a role in risk management.

"I do not think prescriptive rules are often best. And they are often problematic. I prefer to put things in the hands of a supervisory authority, which is better positioned to deal with the nuances of the real world. Black and white rules are usually less effective."

Many in the industry agree. In a letter sent to regulators in November, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association said that metrics - on length of trades, size, etc - should not be used to prohibit proprietary trading, but should simply be seen as flags for banks to look further into that particular trading activity.

Dismantling operations

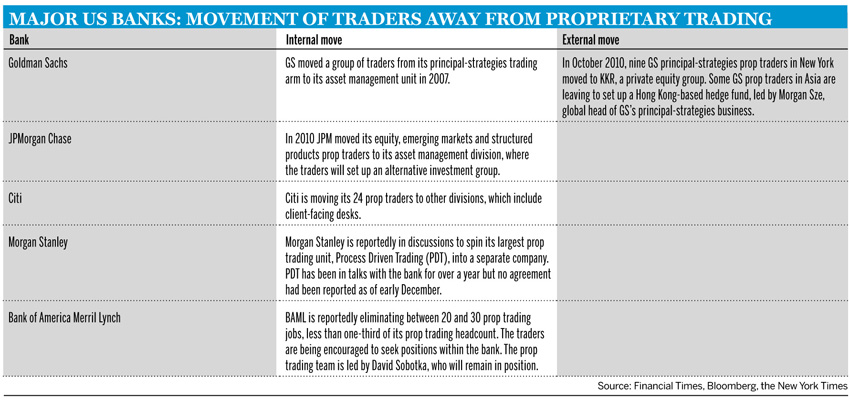

While banks and other groups are still lobbying in Washington, they do seem to have given up the battle to carry on with business as usual. Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan Chase, Citi and Bank of America Merrill Lynch have all publicly declared that they are dismantling their proprietary trading operations.

There are various explanations for this. One is that banks have taken these measures to avoid the risk of losing traders while still holding trading exposures during the period of uncertainty. They have decided it was less risky to close departments and reduce exposures altogether.

Another explanation is that banks have already found ways of getting around the Volcker Rule's prohibitions and are continuing to carry out such activities, although with a lower risk profile and with a new name. "We still do [proprietary trading] here, but with a lower value-at-risk and [we call] it something else," says the head of a trading department at a second-tier bank. "If we do it, you can bet that others do it too." There is no suggestion, however, that the top-tier banks mentioned in this article - Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan Chase, Citi and Bank of America Merrill Lynch - have taken this approach.

This trader is not alone in thinking that some banks will find a way round the rules. A former Lehman Brothers corporate bond salesman, Robert Wosnitzer, who now studies at New York University, has been interviewing Wall Street bond traders for a dissertation on the history of proprietary trading. His findings were reported by Bloomberg in late October. He said traders had been surprisingly open about their intentions to exploit a loophole in the new law: the lack of definition of what constitutes proprietary trading, as opposed to trading as an agent, on behalf of clients.

A relief to stop?

But there may be a third reason behind the quick dismantling of proprietary trading desks - the banks wanted to do it anyway, but had previously been prevented by fear of losing status and revenues. Now that all banks are subject to these rules, they can reduce their risk profile without losing any competitive advantage.

During the boom period, before the crisis, banks' boards of directors felt they had to take on more and more risk to compete. Some now say they also started feeling uncomfortable with how potentially uncontrollable this level of risk was becoming, and with the increasing power given to the risk-hungry traders on the prop desks. "These people often [effectively] ran the banks and demanded more and more," says one senior professional. "Many chief executives would have liked to get together and collectively get rid of some of the traders' activities. But if they had done that, the anti-trust people would have been after them, as it would have been seen as a conspiracy. So the government has done this for them."

An interesting parallel can be found in another business sector that has had its own dark days. In the 1970s, tobacco companies were still allowed to advertise their products and were the biggest broadcast advertisers in the US. Advertising budgets were very large and were eating up a larger and larger portion of companies' revenues. They saw advertising as indispensable because research showed that, although smokers would keep on buying cigarettes without the encouragement of advertisements, their brand loyalty was very low. Tobacco companies therefore allocated a big chunk of their budgets to radio and TV advertising. It was expensive but it had to be done or the competition would have won market share. When the US legislators prohibited it, tobacco companies did protest but as the prohibition affected the whole industry, no competitive advantage was given to any participant, and the advertising budget no longer needed to be spent.

As one expert put it: "Tobacco companies put up a fuss and lost, and at the end it was the best thing that could have happened to them. They didn't have to spend all that money any more. The big losers were the advertising agencies and the TV networks. Something similar is happening now. The government is telling banks they can't do those activities any more and now they're doing what [banks] would have [liked to have] done anyway. It may be that boards of directors and shareholders are happy with the Volcker Rule."

Some argue that in the long term and calculated on a risk-adjusted basis, not having proprietary trading desks would make banks more profitable, and that more competition could be created in investment banking.

Other risky practices

However, some potentially riskier practices are not addressed by the Volcker Rule. These are the direct acquisitions of securities, companies and property assets by a bank - as opposed to investments in funds, which by their nature present more diversified exposure than a direct investment, and therefore should be less risky.

Such direct investments are held in the banking book rather than being accounted for on the trading books. The longer-term nature of such investments and the higher capital requirements they carry would exclude them from the Volcker Rule. These can be highly profitable investments, but they have in the past made significant losses too. The losses generated from Lehman Brothers' principal investments in highly risky real-estate firms, for example, contributed to the bank's fall in 2008. "Principal investment is not included in the Volcker Rule, which is quite interesting," says Paula Haynes, principal in the risk advisory division of KPMG. "There are areas other than proprietary trading where banks can take on risk."

Another consequence of the new regulation is that hedge funds and private equity firms are becoming increasingly attractive places to work for traders, who are seeing their role and freedom in banks constrained by the new rules. While some high-earning proprietary traders have moved to banks' asset management divisions, others have left to join hedge funds and private equity firms, which are also expanding their businesses to include other investment banking activities.

In October 2010, nine of Goldman Sachs' principal strategies proprietary traders, based in New York, moved to KKR, the private equity group that is building an asset management arm; and some of Goldman's proprietary traders in Asia are leaving the bank to set up a Hong Kong-based hedge fund, led by Morgan Sze, global head of Goldman Sachs' principal strategies business.

"The KKRs, the Blackstones and the TPGs [investment firms] are becoming full-service organisations," says Jeff Berman, partner at law firm Clifford Chance. "But [they are not serving] the small-business sector or consumers, they're not high-street banks by any stretch. They are providing what I heard someone saying recently was sources of capital across the board. Their investment strategies have broadened [over the past year] to investing in debt funds, buying troubled assets in one-off transactions, and now a lot of them have their own merger-and-acquisitions advisory businesses."

Mr Groome adds: "Will we see more talented traders leaving the big banks and join the hedge fund community, as we already have? Yes. Will they start up new funds? Yes. Will they join existing funds? Yes. Will investors benefit because they will have more choice? Absolutely. That is also a clear consequence of the Volcker Rule."

So, all in all, despite the criticisms from the financial world, the Dodd-Frank Act and its Volcker Rule could be a much better thing for the banking industry and their clients that any banker would generally admit.

Lucas van Praag, Goldman Sachs' global head of communications, believes so, adding that the tension between the industry and regulators has in any case been blown out of proportion by the press. "It is too easy to characterise this debate as a conflict between market participants and regulators. I don't think it is, and I don't think any major market participant thinks about it that way," he says.

"For us, and firms like ours, the largest risks are in intra-day exposure to other financial institutions. The [big risks] are generally not [exposure] to corporations, because we require collateral, so our exposure to them is very, very limited. Why wouldn't we want our largest-risk counterparties to be properly capitalised and have decent liquidity reserves? We do. And our counterparties should want the same from us."