On the surface, it may seem that the EU's 2007 MiFID legislation, which aimed to create a pan-European investment market on a level playing field, has changed little. However, a closer analysis reveals an industry in the process of change, as new upstarts make inroads and traditional exchanges respond with new technology. Writer Chris Skinner

Two years after the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) came into force in Europe and not a great deal has changed - or has it? There are certainly new trading platforms and new clearing systems, but the general landscape of Europe, dominated by the three largest exchanges - Deutsche Bourse, NYSE Euronext and the London Stock Exchange (LSE) - remains unfazed. Or is it? Certainly there are many pretenders to these giants' thrones, but are any of them really up to the job?

In November 2007, MiFID's rules on transparency of trading came into force. The idea was that we would have a pan-European investment market that would be as transparent, competitive and efficient as the US markets. Various players threw their hat into the ring to shake things up and, two years later, only one is making any major inroads: the Instinet subsidiary, Chi-X.

Meanwhile, the other pillar of MiFID's intent lies untested and unchallenged, namely best execution. However, for anyone to believe that MiFID is a damp squib would be wrong. It has shaken the foundations of the European investment industry by ushering in new technologies, new focus and new pricing systems that, over time, will demonstrate a radical restructuring of the European markets.

Before delving into this territory, let's look at the new competition first.

Chi-x makes an impact

The first mover to leverage MiFID's opportunities was Chi-X Europe, the pan-European equities exchange geared towards aggressive, high-speed algorithmic trading. The fact that Chi-X was the first mover, opening for business in April 2007, meant that by the time the second movers came into the market - Turquoise and NASDAQ OMX started trading effectively in September 2008 - there had been an 18-month cycle of liquidity-gathering which has proven hard to break.

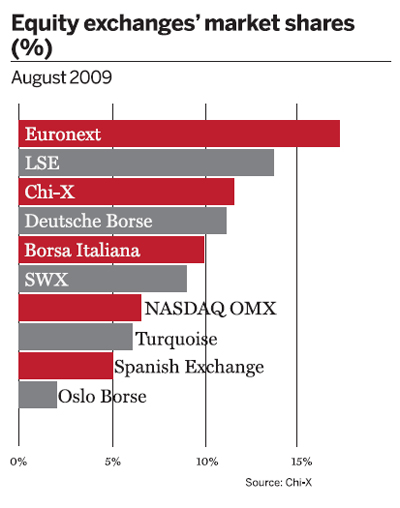

Under MiFID's rules, there is meant to be a requirement for best execution based on the price, speed and cost of processing, but this rule has never been tested and, more often than not, trades flow to established markets. Therefore, Deutsche Bourse, NYSE Euronext and the LSE are still thriving, and the only new entrant to make any headway has been Chi-X.

Chi-X claims that this is based on more than just being first mover, as it offers very low latency (high speed) capabilities for high-frequency traders. For example, the cycle time to process an order through Chi-X is about two milliseconds, compared to six for Turquoise and significantly slower cycles through the traditional exchanges.

This low latency capability has been critical for the main market makers, for whom the speed of trading is central to exploiting fleeting market opportunities.

Other contenders

In addition, the second movers' launch in September 2008 was just a matter of bad timing as this coincided with the market crash prompted by Lehman Brothers' collapse. Launching new equities exchanges just as all market trading volumes plummet was just poor timing.

It does not mean that the new entrants and market restructuring has finished though, as other trading facilities have launched since September 2008 including Equiduct, BATS Europe and Quote MTF. In fact, according to the Council of European Securities Regulators (soon to become the European Securities Authority), there are 125 multilateral trading facilities (MTFs) that have registered for licences with the agency since MiFID came into force.

And most of these facilities have one thing in common: low latency technologies at a low cost.

For example, the average order cycle, including clearing, costs 10 basis points on the new trading venues, compared with 70 or more on the incumbent exchanges. They also operate the so-called 'maker-taker model', under which providers of liquidity receive a rebate if their quotes are met, and firms that hit these quotes are charged for taking liquidity from the platform. Finally, they are also geared towards dark-pool trading activities and electronic liquidity providers.

This last point is a key one as, alongside new equities exchanges, the other major change in European trading has been the rise of dark pools, where orders can sit waiting to be filled unseen. Turquoise was the first aggressive play in this space, backed as it is by the major market makers. Since Turquoise launched, several others have risen including Smartpool from NYSE Euronext, EuroMillennium from NYFIX, and the troubled Baikal from the LSE.

Dark trading

These dark pools may encounter a few issues in the future as they are based on the US model, and Wall Street traders have recently found themselves in hot water over the use of dark pools and low latency to potentially manipulate the markets using an increasingly controversial type of trading strategy, known as flash orders. The way this works is that, through the automated systems for trading, dealers can see a large order entering an exchange half a second before it is filled. That half a second allows them to rapidly process hundreds of orders for the shares about to be traded using algorithmic low latency processing. The result is that by the time the buyer's order is filled, the price has risen by a cent. Perform such trading regularly through the day, and those cents soon add up to a tidy profit for the brokers and dealers using such trading facilities.

These practices are about to be banned by the SEC, and NASDAQ has already said it will not allow them but higher frequency trading in a broader sense is not going away any time soon.

This is concerning the European Commission, even more so with the fact that pricing has become fragmented across so many pools of liquidity, many of which are dark. This is potentially the rule of unintended consequences and the rumours of a MiFID II to resolve these issues abound.

Traditional exchanges

Meanwhile, all of this fragmentation and dark trading is having a major impact on the traditional exchanges.

The traditional exchanges spent many years protected by concentration rules that forced traders in each country to process orders through their national exchange. These rules were removed on November 1, 2007, when MiFID came into force, and has opened the exchanges to major new competitive forces unseen before.

Although these new competitors have struggled to take liquidity, the fact is that some are. Chi-X for example, is processing an average 20% of FTSE 100, DAX 30 and CAC40 shares these days, and Turquoise claims a further 5%.

The prospect of a quarter of the most liquid shares trading on the traditional exchanges moving to the new exchanges in a couple of years is a concern, and each exchange has taken a different route to meet these concerns.

Deutsche Bourse saw a 7% drop on its platform, Xetra, and 14% decline on Eurex trading in Q2 2009 compared with Q2 2008, with only Clearstream's custodial services delivering a bright spot. NYSE Euronext made a $182m loss in Q2, mainly due to severance costs with LCH.Clearnet over its acquisition of LIFFE, the London-based derivatives exchange. And the LSE is in a real muddle, with former leader Dame Clara Furse leaving in a cloud of controversy over the exchange's business strategy and new CEO Xavier Rolet announcing a radical departure in approach.

All change at the LSE

The last point was the most shocking in fact, as ex-Lehman banker Mr Rolet intimated that he was going to dump TradElect, the LSE's flagship system. TradElect was developed by Accenture and Microsoft as a next-generation trading system that went live in the summer of 2007 at a cost of £40m ($66.2m). The system was developed before the impact of dark-pool and low-latency trading however, and has never been able to compete with the order speeds of Chi-X.

Therefore, after only two years, the system looks to have had time called in order to create a real next-generation trading service that processes at the speed of light.

Nonetheless, it remains clear how difficult it is to take liquidity away from a trusted venue. Just before Lehman Brothers' collapse, the LSE had a software failure for several hours on September 8, 2008. During this period, the outage should have led to major moves to the new exchanges as trading became stymied on the LSE for almost a day. This did not happen, however, because most of the pricing feeds at that time were tied to pricing on the LSE and, with no price feed from the LSE, there were no pricing deals to be done on the alternative exchanges.

This will change in due course, as the new players find their niche, but today it is still the case that most traditional exchanges own their markets, or a large part of their markets. Yes, it is being eroded, but only slowly.

Frozen out

The erosion of the traditional exchanges' dominance of their country's securities trading is tied heavily to the openness and access to clearing and settlement in each constituency. Without easy securities settlement at the post-trade end of the process, the new exchanges are effectively frozen out of the markets.

The new exchanges have achieved a fair amount in resolving this issue, with new central counterparty (CCP) clearing systems from the US, in the form of the EuroCCP, a subsidiary of the Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation, and in Europe with Fortis's European Multilateral Clearing Facility (EMCF). But there are still many issues regarding interoperability and access to clearing and settlement in many countries.

Until the European Commission eradicates the Giovannini barriers - the barriers to cross-border securities settlement identified way back in 2003 and still unresolved today - and creates a truly open and transparent post-trade system for Europe, the pre-trade equities trading upstarts can make inroads, but they will merely be narrow roads rather than expressways.

In conclusion, two years after MiFID, Europe has a buoyant and lively marketplace for trading and investment that is gradually moving towards the European Commission's vision of an open and transparent pan-European trading regime. The new MTFs have managed to gain a quarter of the most liquid stocks trading activity, and this will grow even further over time. Meanwhile, the traditional exchanges are rethinking and redeploying new technologies to compete.

The result at this stage is that the liquidity pools of Europe are running deep and dark.