Unlike their counterparts in Ireland and Spain, banks in Portugal are the victims rather than the perpetrators of the country's debt crisis. This should put them in a good position to recover, but limited access to funding and increasing capital ratio requirements are forcing them to change their previously profitable business models.

Portugal’s sovereign debt crisis and subsequent bailout by the EU and International Monetary Fund (IMF) has had a profound impact on the country’s banks. Their credit ratings have been downgraded to junk status, they have been shut out of international capital markets, their share prices have fallen sharply, and all but one of the country's five leading lenders – Banco Santander Totta – posted a loss in 2011.

Editor's choice

From out of this upheaval, however, a stronger, leaner financial sector is emerging in readiness for a post-crisis period of growth and recovery. “The capital ratios of Portuguese banks are higher today than they have ever been,” says Fernando Ulrich, chief executive of Banco BPI. “There has been significant deleveraging. Credit-deposit ratios have improved considerably. The whole system is much stronger than it was two or three years ago.”

Bankers in Portugal see themselves as victims of the country’s debt crisis rather than part of the problem, unlike banks in Ireland and the cajas (savings banks) in Spain, some of which have been accused of reckless lending to property developers. Nor has there been any crisis of confidence in the Portuguese financial system, in sharp contrast with Greece, where bank deposits are estimated to have fallen by more than a quarter – about €70bn – since 2009.

“Deposits in Portugal have been growing steadily,” says a senior Lisbon bank executive. “There has been no property bubble to burst and devalue assets. There was no significant investment in toxic assets. Confidence in the system remains strong.”

Domino effect

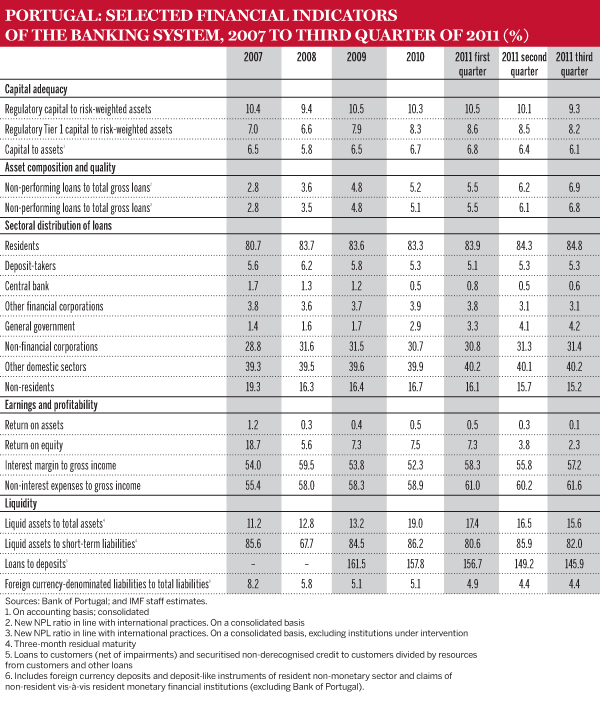

Before the debt crisis, Portuguese lenders were profitable, financially solid and well provisioned, bankers say. Adhering to traditional business models, they posted an average return on equity of 7.5% in 2010. But as the country’s borrowing costs soared, banks came under increasing government pressure to invest heavily in government bonds, triggering a vicious circle of downgrades and falling share values.

Successive cuts in the Portuguese credit rating led to a downward spiral of comparable downgrades for banks. As a result, wholesale funding markets closed to Portuguese lenders, while painful austerity measures required to comply with the bailout agreement aggravated a protracted economic recession, further damaging bank credit ratings. By September 2011, average return on equity had fallen to 2.3%.

In the latest ratings cuts at the end of March 2012, ratings agency Moody’s downgraded or partially downgraded all of the country's largest five banks, saying their asset quality and profitability were expected to deteriorate as a result of Portugal’s poor economic outlook. In addition to an erosion of profits “driven in part by austerity measures”, Portuguese lenders faced additional risks resulting from “substantial holdings of government-related debt”, according to Moody’s. They also had to cope with “prolonged and ongoing lack of access to private wholesale funding”.

Virtually frozen out of funding markets since May 2010, Portuguese banks have been forced, like many other eurozone lenders, to rely on European Central Bank (ECB) liquidity, with accumulated borrowing from the ECB fluctuating between €40bn and €50bn during the past two years, between 7% and 10% of total liabilities. ECB borrowing hit a record high of €56.3bn in March 2012, up 18% on the previous month.

This partly reflected take-up of the ECB’s second offering of extremely cheap long-terms funds, known as Long-Term Financing Operations (LTROs). Lisbon bankers said some foreign banks were also using their Portuguese subsidiaries to borrow ECB funds. The three-year LTRO offerings in December 2011 and February 2012 have considerably eased the liquidity constraints facing Portuguese banks. According to Carlos Costa, governor of the Bank of Portugal, more than 80% of ECB funds borrowed are at three-year maturities, providing lenders with a stable source of liquidity into 2015.

António Vieira Monteiro, chief executive of Santander Totta, says: “The ECB has essentially been serving as a central counterparty for a dysfunctional money market. Even when confidence returns, we expect a structural reduction in the role markets will play in providing bank liquidity. Deleveraging efforts will reduce liquidity requirements and banks that have been frozen out of international markets will think very hard about what kind of market dependency they want in the future.” Mr Vieira Monteiro, a former executive board member, was named Santander Totta’s CEO in January after his predecessor, Nuno Amado, left the bank to become chief executive of Millennium BCP.

Counting the losses

Faced with an economy in deep recession, the one-off cost of partially transferring pension funds to the state social security system and European Banking Authority requirements to improve capital ratios and increase provisions, Portugal's five largest banks recorded a total loss of more than €1.5bn in 2011, with only Santander Totta, a subsidiary of Spain’s Santander group, managing to buck the trend with a net profit of €64.1m. As the economy contracted 1.6% in 2011 – it is forecast to shrink by a further 3.4% in 2012 – growing impairment charges on deteriorating domestic assets also hit yearly results, with non-performing loans accounting for 6.9% of total assets in September 2012.

Millennium BCP, Portugal's largest listed bank by deposits, suffered the biggest 2011 loss at €788.2m, followed by state-owned Caixa Geral de Depósitos at €488.4m. Banco BPI, the smallest of the five, posted a €204m loss, while Banco Espírito Santo, the largest listed lender by market value, recorded a loss of €108.8m. “There was a brave and concerted effort among Portuguese banks in 2011 to pay the cost of additional provisioning, deleveraging and higher capital ratios,” says a Lisbon banker. “They are now in a much stronger position to prepare for the recovery.” Mr Ulrich says that Banco BPI will post a positive result for the first quarter of 2012 and expects to return to profit for 2012 as a whole.

In 2011, the only positive contribution to earnings for most Portuguese banks came from foreign operations, particularly those in the fast-growing former Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique. Overseas assets have typically accounted for 30% to 50% of bank earnings in recent years.

The €78bn bailout package that Portugal negotiated with the so-called troika – the European Commission, ECB and IMF – in May 2011, includes “measures to strengthen the financial sector” as one of its three central components; the others being fiscal consolidation and wide-ranging economic reforms to tackle low growth and weak competitiveness, the vulnerability seen to be at the heart of the country’s difficulties. The three-year economic adjustment programme envisages “a balanced and orderly deleveraging of banks”, ensuring adequate capital to face a challenging economic environment and stronger banking supervision. The €78bn rescue package also includes a €12bn bank recapitalisation fund, which some banks are expected to tap into for the first time before the end of June 2012.

Under the agreement, banks are required to reduce their loan-to-deposit ratios from a peak of close to 170% in 2009 to less than 120% by 2014. By the end of 2011, the average for the banking system had fallen to an estimated 143%, down from 158% a year earlier, as credit to the private sector declined, deposits grew and some foreign assets were repatriated. Bankers are confident the sector will comfortably meet the 2014 target, with BPI, for example, already having achieved a credit-deposit ratio of 110% and Santander Totta 138%.

Mr Vieira Monteiro of Santander Totta says: “We have front-loaded our deleveraging efforts through a mix of asset sales, natural loan amortisations and a strong increase in our deposit base. We don’t expect further deleveraging to pose any restrictions on our activity. Our corporate loan book may even grow if appropriate demand exists.”

Capital strengthening

The turning off of wholesale funding and the need for deleveraging provoked what Lisbon newspapers described as a “deposit war” last year, with banks competing for customer funds at aggressively attractive interest rates of up to 6% and 7%. This hit financial margins and fed into yearly losses as higher loan rates, but diminishing credit growth, failed to compensate for increased deposit rates. The central bank was forced to step in to calm the hostilities, limiting the spread on deposit rates to 300 basis points (bps) over Euribor in November 2011 and to 225bps in March 2012. Maximum deposit rates have since dropped to about 4%.

The December round of EBA stress-tests found Portuguese banks needed to raise just less than €6.95bn to strengthen their core Tier 1 capital ratios to attain the minimum requirement of 9% by 2012’s June deadline. The largest eight banks, accounting for 83% of total banking assets, met the 9% core Tier 1 target for the end of 2011.

The additional requirements are largely to comply with tougher rules for covering exposures to Greek, Portuguese, Spanish and other troubled sovereigns. A special on-site inspection into the quality of Portuguese banking assets, conducted under the supervision of the troika in October 2011, required Millennium BCP, Caixa Geral de Depósitos and Banco Espírito Santo to make additional provisions of €381m, €153m and €125m, respectively.

Capital strengthening also has to take account of the partial transfer of bank pension funds to the state in 2011, an arrangement that raised the equivalent of 3.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) for the state, enabling the centre-right coalition government of prime minister Pedro Passos Coelho to record a 2011 budget deficit of 4.2% of GDP in 2011, comfortably below the official target of 5.9% and less than half the 2010 figure of 9.8%.

Four of the largest five banks will need to raise new capital before July 2012 to meet the new EBA requirements, the exception being Santander Totta, which had already a attained a core Tier 1 ratio of 11.1% by the end of 2011. Banco Espírito Santo has opted to raise capital entirely from its shareholders without tapping into the €12bn recapitalisation fund.

Meeting shortfalls

Apart from being subject to conditions for accepting public capital, including, in the words of the troika, “specific management rules, a restructuring process and restrictions in line with EU competition requirements”, agreeing to state intervention is seen as a deeply emotional issue for the Espírito Santo family, who were stripped of their assets and forced to leave the country in the wave of nationalisations that followed Portugal’s 1974 'Carnation Revolution'. They later bought the assets back when most of the banking sector was reprivatised in the early 1990s.

In April 2012, Banco Espírito Santo announced a rights offering of up to €1.01bn to meet the new capital requirements. The bank’s core shareholders, representing 50.63% of its share capital, have agreed to exercise their full subscription rights. A syndicate of investment banks is to underwrite the remainder of the offering. Banco Espírito Santo is offering the new shares at a subscription price of €0.395 each, a discount of almost 66% on the closing price before the announcement. In December 2011, the EBA calculated Banco Espírito Santo’s capital shortfall at just less than €1.6bn.

Banco Espírito Santo said the issue would increase its core Tier 1 ratio from 9.21% to 10.75%, based on risk-weighted assets at the end of 2011. This will meet both the EBA requirement and the Bank of Portugal’s stipulation that Portuguese banks achieve a 10% ratio by the end of 2012, although this is measured differently. News of the Banco Espírito Santo rights issue, its third since 2006, led to a sharp fall in its share price. Overall, the bank will have raised a total of more than €3.5bn from shareholders from the three capital increases. Ricardo Espírito Santo Salgado, the bank's chief executive, says that he hopes the rights issue will constitute a first step towards Portugal being able to resume financing its sovereign debt in the market in September 2013, as envisaged in the bailout agreement.

State-owned Caixa Geral de Depósitos, Portugal’s largest bank by deposits, is expected to rely partly on an injection of public funds to meet its capital shortfall of €1.83bn. Millennium BCP and Banco BPI, which need to raise about €1.7bn and €1.4bn, respectively, plan to draw on the state recapitalisation fund. They also expect to raise smaller amounts of capital from shareholders. Negotiations on the basic rules governing the provision of state support resulted in legislation that came into force in February 2011. But a ministerial order setting out the details had not been published by mid-April as bankers, regulators and the government tussled over the fine print. The delay led Millennium BCP and Banco BPI to postpone their annual shareholder meetings, originally scheduled for late April.

Government intervention

The government has made clear to the satisfaction of bankers that it has no interest in managing banks or becoming a direct shareholder. This principle will be upheld by injecting state capital in the form of so-called high-trigger contingent convertible bonds or 'cocos', which convert into equity if a trigger such as a bank’s core capital ratio breaches a predefined floor. Banks have submitted plans for paying down the loans within five years, with escalating interest rates encouraging early repayment. Overall, the state could earn up to €250m a year in interest from the capital.

For political reasons, government conditions for accessing the recapitalisation fund are expected to include clauses on remuneration and bonuses as well as calling for adequate bank lending into the economy. However, bankers do not see such measures as having any significant impact on management, particularly as they attribute declining corporate lending to falling demand caused by the recession rather than bank deleveraging. “We don’t think there’ll be any state interference in the management of the bank, which will continue to be run by its shareholders,” says Mr Ulrich.

Bankers have been understandably cautious about accepting state capital given the scale of the intervention. Even if only about half of the €12bn fund goes into banks, as expected, this would represent several times the market capitalisation of the listed banks involved. A state injection of €1bn would be more than BCP’s current market value of less than €800m and more than double BPI’s market cap of below €400m. At the same time, raising capital from shareholders, as the Banco Espírito Santo rights issue shows, will require banks to offer shares at heavy discounts to market prices.

Banking shift

One senior executive says that injections of state capital would create “two different types of banks” – those focused on “generating enough income to pay back the state” and those “with the opportunity to gain market share”. Whether or not that proves true, bankers agree that business models are changing. Retail operations previously based on cross-selling other banking products to a large base of mortgage customers are now focusing much more strongly on lending to small and medium credit-worthy companies in the export sector and on generating a higher turnover of fee-paying transactions across the board.

Funding sources are also shifting. “The use of capital markets for funding is a relatively new phenomenon for Portuguese banks that doesn’t go back much more than 10 years,” says Mr Ulrich. “In moving back towards deposits as our main source of liquidity, we’re returning to way banks were run here some 20 years ago. It’s very difficult to foresee when markets will reopen. Until then, we’re managing the bank on very conservative principles, as if funding markets simply didn’t exist.”

Portuguese banks, like Portugal itself, face an uphill climb out of the debt crisis and the country’s worst recession in more than 30 years. Working to ensure that their banks emerge agile, resilient and financially sound, bankers are hopeful that long-postponed economic reforms now being implemented will create a more competitive, export-driven economy in which they can thrive. But they are not expecting an overnight turnaround. As Mr Vieira Monteiro says: “The path to recovery will be slow and full of ups and downs”.