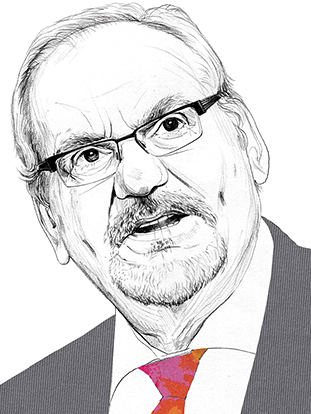

Outgoing CEO of the World Bank’s private sector arm, Philippe Le Houérou, on its commitment to support the countries most in need during the global pandemic.

In March, as Covid-19 began to spread across the world, the World Bank’s private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), was swiftly equipped with $8bn in emergency funding to deal with the immediate economic damage of the pandemic. This was a substantial part of the World Bank’s total $14bn fast-track financing to support both companies and governments during the crisis. Those measures, says the IFC’s outgoing CEO, Philippe Le Houérou, are aligned with the commitment to support the world’s poorest and most fragile countries — and proof that even a global, weighty institution like the IFC can move quickly. As he prepared to leave the organisation he had overseen for the past four years in September, Mr Le Houérou talked to The Banker about the importance of taking a more modern approach to development finance.

Q: How has the IFC dealt with lockdowns and travel restrictions that paused essential field work to evaluate new clients?

A: It has been challenging, as for everyone else, because we have been working from home. We had to work only with existing clients because we needed to be faster. We have very stringent rules on integrity and very high standards on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors. With new clients, it takes much longer to investigate these factors and when you are in lockdown it’s even more complicated. Through our partner banks in emerging markets, we deal with about a million small and medium-sized businesses, which is not a small number. You need to try to do good where you can and, when you can, do it fast.

I must also say that I’m very proud of two things: over the past few months, our IT system worked perfectly well — and I remind you that we have 108 country offices and are opening another two — and our staff found new ways to work. We can’t do field work because of travel restrictions, but we can still do appraisals on video. It means more preparation; in some ways it can be more intense, but it works. The type of work that is very difficult to ‘compress’ and evaluate through a video call is not around financials; it’s work on environmental and social standards, where you need to visit the facilities, and ask about their social policies and how they are implemented. We use satellite images for certain environmental aspects, but it’s much harder. But this has also shown that, sometimes, it’s not completely necessary to travel. So it will have implications on the way we conduct business and on the way we make decisions.

Q: How have you dealt with environmental and social assessments, which, as you say, are much harder or impossible to compress? How much longer are those replacement measures sustainable?

A: We try to be creative, by leveraging non-governmental organisations’ expertise and presence in the field. But there is only so much we can do. If this crisis continues for too long, there will be difficulties and it won’t be on the finance side of things, not on the analysis — it will be on ESG factors and this is something that we take extremely seriously. We rate our projects in terms of ESG by categories one to four; so if you’re in category four, it means that you represent a strong risk and we must go and visit in person. In those cases, there’s nothing that can replace sending our specialist staff to conduct the initial evaluations.

Let’s assume that this crisis continues, with ups and downs, for another two years — then we may hit the limit of what we can do. This is despite trying to find proxies around some of those issues, despite our teams being very agile in the way they work and the fact that, thanks to our country offices, we already have a local connection. But there is a limit. I don’t know where exactly, but it is there.

Q: How is the current situation influencing the debate over the need for development finance and its future shape?

A: Development finance institutions will be more relevant than ever. Our colleagues at the World Bank had a record year. And something new has happened for the IFC: I got phone calls from prime ministers and ministers of finance asking for help to support their small and micro companies. So we’ve been developing, with our colleagues from the World Bank, an advisory service to governments on how to try to keep viable businesses afloat. We engage much more with governments on reforms. In many countries, the laws on bankruptcy are very penalising. Changing these laws would give those companies a chance.

When we meet with other development finance institutions, we always lament that there are not enough bankable projects. But I say: let’s design them. Let’s design bankable projects for South Sudan, for example. That is what was needed before Covid; after Covid, it will be needed even more. Private investment will not bounce back anytime soon. What we can do is accelerate this process by taking it upon ourselves to carry out market analyses, feasibility studies and, once ready, we can de-risk and help finance those projects.

Q: In spite of this, attacks on multilateralism have not abated, not least from the current US administration. Does multilateralism have a future?

A: No one votes for multilateral institutions, unlike for governments. Multilateralism is an important part of a bigger discussion that includes diplomacy and trade. But the aid architecture will be very different in the future because most governments, the traditional donor governments, will come out of this crisis with very weakened budgets. During my own career — in my 32 years with the World Bank — I see that this, in these times of crises, is when ministers of finance talk more and more about public–private partnerships. We need to bring the private sector to the table and we need to guarantee that projects are good investments.

If you are a pension fund manager, you want to make sure that your investments can eventually fund those pensions. We can sweeten a risky deal by having a panoply of instruments to unlock savings that will find good returns and that will do good in countries that need those investments desperately. We need to work on the risk/return equation.

I don’t think that official development aid will increase, it may decrease — and then what happens if there is no private investment? There will be no jobs. Healthy employment is important for the prosperity of the world, its stability, and — I know it’s a word that may sound strange in this context — dignity. Human beings’ dignity, to have a job, is fundamental.

Q: Since joining the IFC in 2016, your strategy has been to work even more closely with the private sector. As you’re about to step down, what do you hope your legacy at the IFC will be?

A: What is important now is that we are organising ourselves to work ‘upstream’, so that we don’t need to wait for projects to come to us. It sounds very simple, but it means a huge change in the way we do business. It means working much more closely with the World Bank. That means also engaging more with governments, in addition to the private sector. It’s very hard to finance an infrastructure project if you don’t work with governments. It’s very hard to support the financial sector, which is a highly regulated sector, without working with monetary authorities and ministries of finance.

As for my legacy, I hope that the IFC will deliver on the commitment to triple our support to International Development Association (IDA) countries [the world’s 74 poorest countries assisted by the World Bank’s IDA]. This is critical because this is where we make a difference. We are a frontier bank. We don’t have to do what BNP Paribas, JPMorgan, Citi or others can do very well already.

When I started my career in development finance, my first mission was in China. It was a very poor country; now they are a big contributor to the IDA. The world has evolved and we have to evolve too. What worked before may not work now, so we need to experiment, to be more open, and to create markets and projects. If, in a few years, I see that a big chunk of the IFC’s new lending was generated by feasibility studies or reforms that were pushed by us, I would think that my fours years here were well spent.

I grew up in Africa and I dedicated my whole life to economic development. I want to stay engaged, that’s for sure, but without necessarily the weight of being the IFC’s CEO on my shoulders.

Philippe Le Houérou is the outgoing chief executive officer of the International Finance Corporation. This Q&A has been edited for brevity and clarity.