Chilean Finance minister on rescues and recovery

The finance minister of Chile discusses the country's "very exceptional" fiscal situation, and tells how it is recovering from an earthquake that shattered the country earlier this year. Writers Jane Monahan and Brian Caplen

Click here to view an edited video of the interview

Felipe Larrain had good reasons for looking cheerful at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) meetings last month. At the time, a plan by the Chilean government to rescue the 33 miners trapped in a mine in the north of the country - whose fate has grabbed the attention of the world's media - was about to reach a positive outcome. The news is especially welcome in Chile, a nation where mining accidents have led to fatalities in the past. "All the country's attention has been fixed on the fate of the miners. Ours is a very religious society so most of us were praying for them," says Mr Larrain.

Another piece of good news is that in September the IMF published a broadly positive report on the Chilean economy, in spite of the challenging times of the past two years - a global recession and then, just as the country's economy was recovering, a devastating earthquake. The disaster killed 500 people and caused about $30bn of dam-ages. Before that, economic growth had contracted by 1.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2009 and 50,000 jobs had been lost because of the recession.

But, according to Mr Larrain, the country is definitely past the worst of both events. Chile's transport system - crucial in a nation that is ribbon-shaped and a full 4300 kilometres long - has been reconnected where it was broken by the earthquake. And, after last year's downturn, its economy has rebounded - GDP growth has been at least 7% in each of the past five months. According to Mr Larrain, the big rebound is due to three factors - the government's post-earthquake reconstruction work, the fact that the growth started from a very low base, and confidence in the economic policies of the country's president, Sebastián Piñera. Mr Piñera, who was elected in January and took office in March, is Chile's first conservative leader since General Augusto Pinochet's departure in 1990.

Meanwhile, the IMF report was not only positive about Chile's economy. It also praised the country's government for setting up a multi-party commission, and accepting its recommendations on transparency issues in connection with the application of a fiscal rule established during the crisis, aimed at maintaining a balanced budget with counter-cyclical policies. The rule was broken in 2009. However, with an estimated fiscal deficit of 3% of GDP this year, a commitment by Chile's president to reach a 1% deficit by the end of his term (in 2014), plus a public-sector debt ratio of just 6%, Mr Larrain can afford to eschew false modesty. "Chile's fiscal situation, if you compare it with the rest of the world, is very exceptional," he says.

Capital controls

Implementing a new economic programme, an earthquake reconstruction plan, and consolidating the country's fiscal situation, would seem enough of a challenge for a finance minister relatively new in the job. However, an additional consequence of having a strong economy and a good fiscal situation is that this tends to attract speculative, or 'hot', capital inflows (as is currently happening in Brazil) which, in turn, can lead to an over-strong currency. Such a situation sometimes calls for capital controls.

Efforts are being made to prevent an unnecessary appreciation of Chile's currency, the peso, says Mr Larrain. He adds that this concern does not extend to fluctuations in returns in the mining sector. Chile is the world's biggest copper producer and the recovery of international copper prices to $3.80 per pound, compared with just $1.40 in the trough of the recession, was badly needed.

On the other hand, the government is adopting various domestic prudential measures to help cool the economy, such as holding government spending below GDP growth. In the 2011 budget, for example, government spending is due to increase by 5.5%, which is less than that year's forecast of between 6% and 7% growth.

The financing of the budget is from a variety of sources. In an unexpected move for a centre-right government, albeit a clear sign of its pragmatism, taxes are going to be raised, most of them transitorily but some of them permanently. "The earthquake was unexpected. The net cost for the government is more than $8bn and we need to get some of that from taxes, in order to be responsible and not just to spend and increase the deficit because of the earthquake," says Mr Larrain.

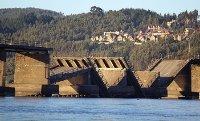

Building bridges: Chile suffered a devastating earthquake earlier this year, and the repair bill for the country's infrastructure is set to top $8bn, part of which will be raised from a tax rise

Watch the videoInterview with the Finance Minister of Chile – IMF |

Managing risk

Another initiative is that the Chilean government is making it easier for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which provide most of the country's employment, to have access to currency hedging instruments such as options and futures, that they normally do not use.

Also, through Chile's state-owned bank, the government is making dollar loans available to SMEs, whose earnings are in dollars but whose liabilities are in pesos, to help them manage currency exchange risk.

Mr Larrain does not rule out the possibility of interventions by the Central Bank of Chile should the appreciation of the peso become too big, or be too rapid for stability. This has been done before. Chile has a floating exchange rate. But in the past 10 years the central bank has heavily intervened three times.

However, many observers say, what is most significant in view of Chile's recent past is that Mr Larrain has ruled out reimposing capital controls to stop speculative capital inflows. "We had an experience [in the past] of capital controls and we don't think it is the right way to go," he says. At least in this respect the government's conservative and free-market economic policies are as expected.

Finally, in a move to diversify sources of financing, the government placed $1bn in 10-year bonds in July, at a yield of 90 basis points, or 0.9% above US Treasuries, which were the tightest spreads in Chile since the beginning of the 19th century.

The government went to the market to raise money for the reconstruction effort and to establish a good benchmark for Chilean companies. It paid off grandly - very soon after the dollar bond placement the South American country also sold $520m of bonds in pesos at 5.5%, cutting about 60 basis points, or $24m, from the cost of borrowing in its own currency.