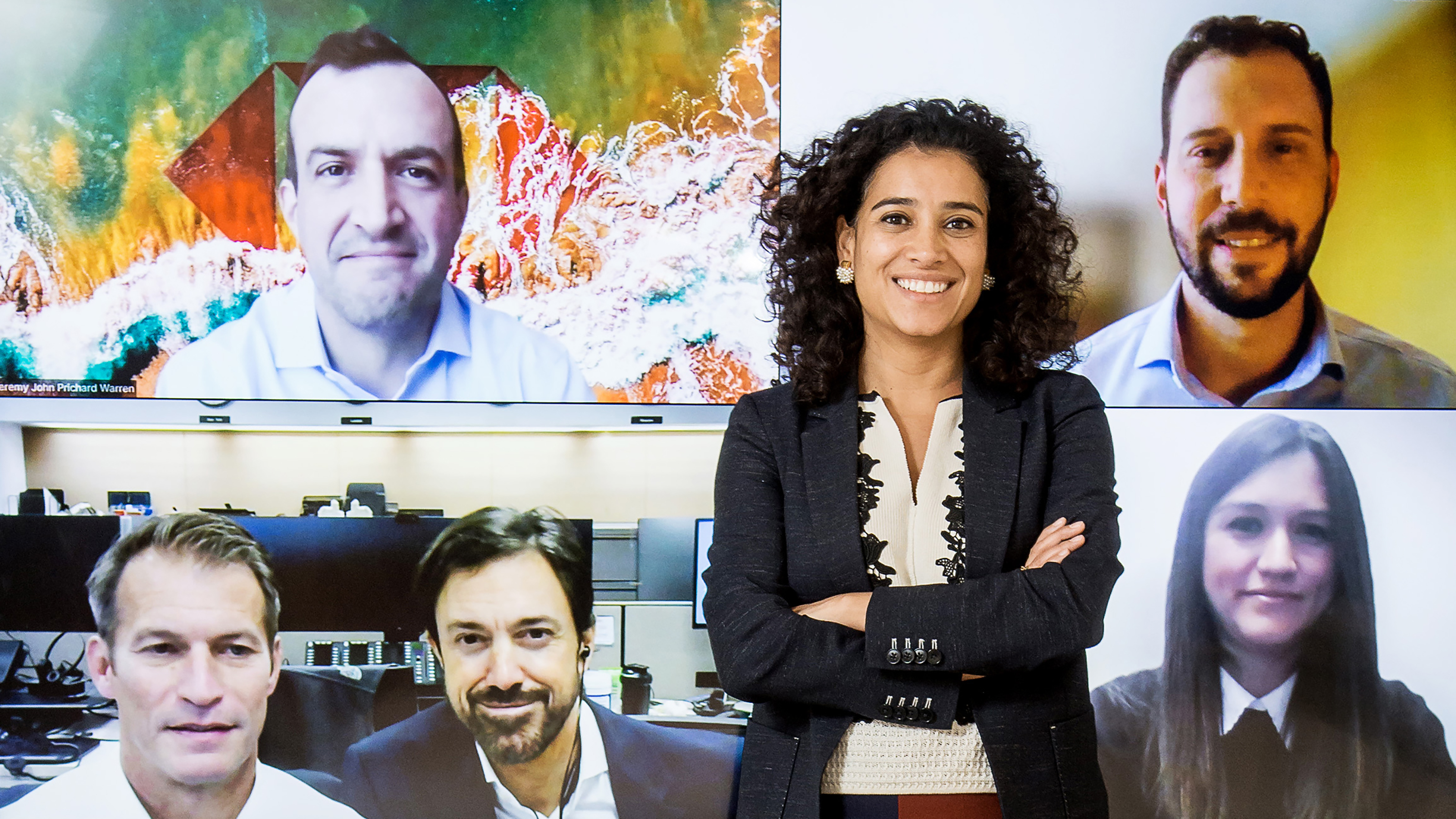

Top row: Jeremy Warren, Mik Breiterman-Loader. Bottom row: Russell Ashcraft, JP Gallipoli, Nora Rodriguez Ponce. Centre: Anjuli Pandit

The sustainability-linked bond provides a way for Uruguay to highlight its commitment to the Paris Agreement by introducing financial consequences for missing its sustainability targets. Edward Russell-Walling reports.

Uruguay has issued the world’s first-ever sustainability-linked bond (SLB) with a two-way coupon step structure, penalising the sovereign if it fails to meet sustainability targets but also rewarding it if they are met. HSBC was joint sustainability structuring bank and bookrunner, as well as billing and delivery agent on a simultaneous switch tender.

Since the end of military rule some four decades ago, Uruguay has arguably become the most progressive state in South America. It has an admirable recent record in democracy, tolerance and economic freedom, and is the highest-ranking Latin American country (and 18th in the world) in the latest Corruption Perceptions Index, where higher is better.

That ethos has informed the government’s attitude towards the environment and climate change, not least because Uruguay is vulnerable in this regard. Though it is the continent’s second-smallest country, its coastline stretches for over 400 miles and 70% of the population lives near it.

Earlier this year, Uruguay launched a national climate change adaptation plan for the coastal zone. It was an early mover in cutting carbon emissions, and for some years now has derived nearly all its energy from renewable sources.

Sustainability criteria

The Uruguayan finance minister is Azucena Arbeleche, an economist and the first woman to occupy this position. Ms Arbeleche knows her way around the debt capital markets (DCM), having run the ministry’s debt management unit before leaving to enter politics.

“She was a key sponsor of the decision to go with this structure,” says Anjuli Pandit, HSBC’s head of sustainable bonds for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, and the Americas.

The issuer had a strong commitment to the climate change mitigation goals of the Paris Agreement, but was conscious of the fact that there were no financial consequences for non-compliance, according to JP Gallipoli, a New York-based HSBC director, DCM who specialises in sustainable bonds.

“The SLB provided a way for the [country] to highlight its commitment to the Paris Agreement, to introduce financial consequences for non-conformance and to create positive incentives for Uruguay to outperform its targets,” Mr Gallipoli says. “Thinking beyond the transaction, the structure pioneers an alternative approach for sovereign sustainability-linked capital financing.”

The issuer was keen to issue an environmental, social and governance (ESG) bond and discussed the merits of SLBs versus a use of proceeds format with bankers from early 2021. Having consulted widely, it decided that an SLB was the best way of aligning the state’s financing strategy with its environmental objectives, linking its cost of capital with the achievement of Paris Agreement goals. In early 2022, it mandated four banks for a transaction: HSBC, Crédit Agricole, JPMorgan and Santander.

“Uruguay has always been very innovative in its debt-management strategy, and on this deal there was an alignment with our focus on sustainability,” says Nora Rodriguez Ponce, HSBC’s head of public sector, Americas.

Structuring an SLB

HSBC’s relationship with Uruguay goes back a decade or more. The bank has a local presence, with a trading desk in the capital, Montevideo, dealing in local currency and US dollar assets. It has also been billing and delivery agent on seven of Uruguay’s eight switch-tender offers since 2013.

Structuring an SLB with a two-way step was always going to be a bold and ambitious course of action. Ms Pandit recalls preparing for the first-ever SLB, for Italian utility Enel, issued in 2019. “We did work on a possible step up and down structure,” she recalls. “Investment-grade investors were not comfortable with the idea of a step down.”

It seemed that more time would be needed before investors were ready for this. “It needed the right issuer and the right story,” Mr Gallipoli believes.

The education process was long and thorough, involving meetings with investors over an extended period. “We laid out what we wanted do and worked with their concerns,” says Russell Ashcraft, director of US syndicate at HSBC. “The market felt that they had a say.”

Those concerns included just how stringent the sustainability performance targets (SPTs) would be. Investors took comfort from hearing that SPTs would be set so that, in terms of probability, a step-up would be more likely than a step-down, Mr Ashcraft reports. The step-down SPTs would be set to reflect a really extraordinary level of performance.

In the end, after hearing investor views, the issuer settled on two key performance indicators (KPIs). One was the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions as a percentage of gross domestic product; the other was the maintenance of native forestation by area — a proxy for the country’s carbon-capture capacity.

The bond was designed with input from across government, representing the joint effort of five ministries: economy and finance; environment; livestock, agriculture and fisheries; industry, energy and mining; and foreign relations.

The project also had technical and financial assistance from the Inter-American Development Bank and the UN Development Programme (UNDP). Emission reporting will be annual, with forestation reporting every four years, both externally verified by UNDP.

The relevant technologies come from the private sector, but we need the sovereigns’ support and push

One feature that many investors liked was that they would be able to track Uruguay’s nationally determined contributions in terms of emissions online on the debt management unit’s website.

It makes sense for a sovereign issuer to take the first step with this type of structure, because only the state is in a position to influence national environmental or social outcomes. Ms Pandit notes that the deal was structured specifically so that other sovereigns could copy it, particularly in emerging markets.

“We need to lead via the sovereigns,” she says. “The relevant technologies come from the private sector, but we need the sovereigns’ support and push.”

Roadshow

The deal was launched on the back of a week-long framework introduction non-deal roadshow, followed by a two-day deal roadshow, involving around 100 investor meetings. The structure was not to everyone’s taste and a handful of big US accounts did not like it, but other investors were very enthusiastic.

“Some investors were excited at the inclusion of emissions and forestry KPIs,” says Mik Breiterman-Loader, HSBC sustainable bonds lead, Americas. “They thought this was an innovative transaction, which set an example for broader application.”

At the same time as launching the SLB transaction, Uruguay also executed a one-day switch-tender offer. This targeted outstanding US dollar bonds maturing in 2024, 2027 and 2031. “Holders had the option of switching into the new SLB or selling for cash,” says Jeremy Warren, HSBC’s global head of liability management.

The SLB itself was marketed to the whole ESG investment community, as well as traditional sovereign investors. This was Uruguay’s first visit to the US dollar market for some time, which did nothing to dampen demand.

And demand there certainly was, in strength, with individual orders in some size. Orders totalled some $4bn from around 190 accounts, including several first-time buyers and non-traditional emerging market buyers. Around $3.4bn of the order book was from new cash buyers and $600m from existing holders of target notes.

The order book held up, in spite of hawkish comments on the day from the Philadelphia Federal Reserve president. The final deal, maturing in 2034, was sized at $1.5bn ($1bn new money) with a 5.75% coupon. The 5.935% reoffer yield represented a spread of 170 basis points (bps), having tightened by around 25bps. The coupon steps down by 15bps if the higher of two SPTs is achieved, and steps up by 15bps if the lower SPT is not. Outcomes in the “neutral” range in-between mean no coupon change.

In getting the deal and switch away successfully, Uruguay achieved other goals of completing its 2022 international funding needs, diversifying its investor base, mitigating refinancing risk and extending the average time to maturity of its debt.

“A key validation was that the deal priced at no additional concession relative to other sovereign transactions since the market reopened in August, and arguably at a small greenium,” Mr Gallipoli says.