Tension between the US and China, coupled with disruption from Covid-19, could spell disaster for Africa’s evolving trade finance sector, unless emerging technologies step in to do the heavy lifting.

Since the 1960s, when many African countries gained independence, the continent’s trade finance has met with episodic economic shocks and crises. The history of African trade can be delineated into three main epochs: the immediate post-independence era (1960-1980s), the global debt crisis (the 1980s-2000s) and the post-debt crisis period (2000-2019).

Before the liberalisation of the African commodity trading sector, different economies conducted their exports through commodity boards which purchased commodities from farmers, through licensed buying agents, at prices fixed by the government or by the boards themselves. As the boards supplied the farmers with production inputs, and were the only parties selling the commodities internationally, they absorbed the global price and other trading risks on behalf of the farmers.

From a financing standpoint, these kinds of monopsony and monopoly structures presented excellent financing risk and provided several other advantages. Therefore, most international banks provided trade finance on a clean basis, with commodity trading arrangements hinging on the boards, which banks saw as trustworthy lending partners. The facilities ranged from one-off repayable disbursements to multi-instalment disbursements, revolving permanently, but typically with maturities not exceeding three years. Thus, the arrangements provided an orderly platform for balance of payment and trade financing.

In the mid-1980s, a sovereign debt crisis in Latin America evolved into a global financial/economic crisis which triggered economic weaknesses in developing countries, on account of significant contractions in demand for commodities. A consequence of these developments was mass defaults on international debt obligations by African and other developing countries. Some declared moratoria on debt repayments and many letters of credit payments could not be honoured, creating backlogs of unpaid trade debts.

Trade finance flows to Africa declined sharply. Regulators in mature markets demanded full provisioning for any loans to Africa with maturities exceeding one year. Due to the shortage of trade finance, the cost also rose. According to the African Development Bank (AfDB), the cost of trade finance to African traders in the late 1980s averaged 15% of the value of imports, compared to an international average of 1.5% to 2% at that time.

As the performance of the African economies deteriorated in the late 1980s, the structure of the financing provided by international banks to African economies evolved into what is now known as structured trade finance (STF). Under STF, lenders focused on the boards and avoided balance of payment financing, as they provided collateral structures that mitigated the risk of rescheduling unsecured loans to African economies at that time.

Reforms and recovery

As a consequence of the international debt crisis, the Bretton Woods institutions pushed for economic reforms across the continent. The policies implemented under the structural adjustment programme favoured privatisation of economic activities and dismantling of the commodity boards. It was evident that the suggested policy changes ascribed to growers and private sector exporters a remarkable ability to learn the intricacies of exporting to fill the vacuum created by the demise of the boards. Regardless, it would appear that the banks were not convinced of this implicit trust because they saw new risks in financing the emerging private sector. It is, therefore, not surprising that countries which hastily liberalised, such as Cameroon and Nigeria, found that external commodity financing was hard to come by in comparison to the kind of support received from the Ghana Cocoa Board.

From the 2000s, the prominence of STF waned as developing countries began to recover economically. Sweeping political reforms accompanied the economic recovery in Africa, culminating in an improved investment climate. The creditworthiness of African countries improved partly as a result of the debt forgiveness under the IMF’s Highly Indebted Poor Countries Initiative. The most significant developments were the entering, mostly for the first time, of African sovereigns and corporates into the global debt capital markets, along with the arrival of China into the international trade scene and its rapid growth in trade and investment relations with Africa.

Starting at about 3% in the early 2000s, China became Africa’s largest trading partner by the start of the 2010s, accounting for more than 17% of the continent’s total trade. The expanded trade relations with China and other economies in the global south boosted access to export credit agency financing flows into Africa. China Eximbank, for instance, became a significant financier of trade-related investments in Africa. Added to the remarkable shift was the acceleration in globalisation, accompanied by the emergence of regional and global supply chains.

Covid-19 has thrown up new challenges to global and African trade. The pandemic, together with the US-China trade tensions, have disrupted global supply chains and impacted African trade and trade finance. International banks have cut credit lines to most vulnerable developing countries, mostly in Africa. The Covid-related decline in export receipts and deteriorating loan quality have constrained approvals of trade finance credit lines and worsened the trade finance gap. The AfDB has also suggested that, because trade finance transactions are mostly paper-based and require physical contacts, limited in-person interactions can hinder commercial banks’ ability to conduct thorough due diligence. This could result in a slowdown in approvals and decreased supply of bank-intermediated trade finance.

Digital revolution

The good news is that Africa is now better equipped to manage the trade and economic impacts of global shocks. A confluence of instruments and recent geopolitical dynamics have shaped Africa’s response to recent crises, and will shape the contours of trade and trade finance in the medium-to-long term.

Digital technologies are rapidly altering the traditional approaches to trade, trade finance and payments globally. These technologies are driving down the cost of trade finance, increasing transparency and reducing credit risk, while enhancing the efficiency of trade flows. While traditional modes of trade and trade payments decreased rapidly, e-commerce and digital payments were immune to the Covid-19 crisis.

Global e-payments remained firm even amid the pandemic. Data from Statista shows that e-payments will increase from $3.86tn to more than $4.41tn between 2019 and 2020. E-platforms have enabled financial institutions to expedite credit approvals and disbursements, leapfrogging the challenges of paper-based credit documentation as well as in-person interactions required for traditional trade finance structures.

Africa has been the largest beneficiary of this digital revolution. The rapid mobile penetration and the rise of mobile payments have boosted financial inclusion and development. Data-driven trade finance interventions are likely to emerge and drive increased access to trade finance even for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). An emerging situation in this area that is most likely to transform the continent’s financial architecture is the anticipated Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) – sponsored by Afreximbank in collaboration with the African Union and some African central banks. PAPSS enables payments for intra-African trade to be made in African currencies. It brings two critical changes to Africa's trade finance: minimising the use of hard currencies in trade payments; and domesticating payments and settlements within Africa. PAPSS will help traders and their financiers manage currency risks better.

The ongoing reordering of global supply chains has implications for African trade and trade finance. It presents a unique opportunity for Africa to accelerate the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). The reality, though, is that under the AfCFTA, intra-African trade will involve countries with high-risk perceptions and will mostly evolve around SMEs in export supply chains. The implications of this are many: new financing structures have to be created; supply chain finance, reverse factoring, STF and packing credit will become appropriate instruments; international banks may retreat from financing intra-African deals, due to the high-risk perceptions associated with intra-African trade; and African banks will have to improve internal capacities, through recapitalisation and policy supports, to bridge the gap.

Additionally, the role of regional and continental financial institutions and export credit agencies in de-risking trade will be crucial to unleashing commercial funding for intra-African trade. Afreximbank’s guarantees and credit insurance offerings by other institutions, including the African Trade Insurance Agency, will also become essential in that context.

Despite the recent Covid-19-induced downturn in trade financing in Africa, the severity of the decline has partly been muted by recent developments that are safeguarding against global shocks. The rapid penetration of digital technologies, the recent expansion of Africa’s financial sector, as well as the launch of the AfCFTA have combined to reshape Africa’s trade finance landscape. A considerable part of the changes expected in this landscape will come from Afreximbank. Through its innovative products, such as PAPSS, payment and other challenges that have plagued African trade for several decades are likely to be eased, helping to reduce the risk of financing intra-African trade.

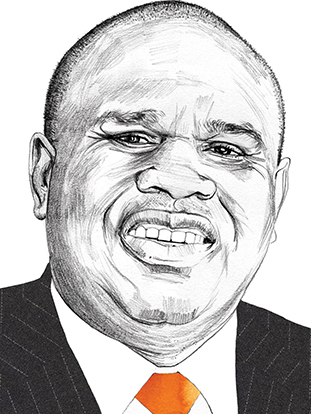

Benedict Oramah is president of Afreximbank.