There is nothing like a major crisis, the collapse of several large banks, government bailouts and plummeting stock markets to shake up views on the ideal model for the financial markets. If the 1990s were characterised by the shareholders’ return mantra and the winning formula of the listed company, distrust in capitalism has been the overriding theme in the post-Lehman world. Only a couple of decades ago, many thought that alternatives to large, listed banks – such as co-operative lenders – would end up extinct; now these alternatives have acquired a new appeal.

“Ten years ago everybody was thinking that mutual banks were going to disappear; at that time everything was market oriented and what was not capitalist was bad,” says Olivier Pastré, professor of economics at the Université de Paris VIII.

The prevalent view at this time was that co-operative banks took up market share that could be better exploited by other banks, says Gerhard Hofmann, board member of the national association of German co-operative banks, BVR, which has 16 million members and 30 million customers. “In the 1990s, there was a strong sentiment that you need large banks, big is beautiful, and risks were not so much taken into account," he says. "The co-operative model was close to being discredited. [Co-operatives were] a source of lower profitability in the banking market, preventing banks from being more profitable.”

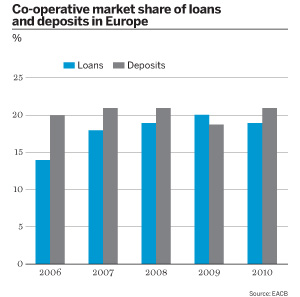

Today, however, co-operative banks account for about 20% of the deposit market in the EU, according to the European Association of Co-operative Banks (EACB), and in France and the Netherlands, co-operative banks account for 45% and 40% of deposits, respectively. One in every three European small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is served by a co-operative bank. Worldwide, according to the International Labour Organisation, credit unions operate in a total of 100 countries with 51,000 unions and 200 million members. They have $1564bn in assets, $1223bn in deposits and $1016bn in loans.

Cashing in on a crisis

The co-operative model has been more stable and efficient than many economists had predicted. Commenting on the performance of co-operative banks, Johnston Birchall, professor of social policy at the UK’s Stirling University, says: “In Europe and North America, there was a slight dip in 2008 and then you see them coming back in 2009, 2010 and 2011. In credit unions in other parts of the world, you can see that they didn’t even face a drop in 2008. They didn’t notice the banking crisis; they just kept on growing slowly but regularly.”

According to a survey of retail bank customers by consultancy Oliver Wyman, co-operative banks have helped retain trust in the banking sector in the aftermath of the financial crisis. In the firm's survey, conducted in December 2011, 55% of the 1123 respondents said that they have become worried about the financial services industry, with 20% having lost trust in the industry altogether. While trust in the financial industry has decreased, the survey shows that customer trust in co-operative banks has, for the most part, increased.

In the UK, the Co-operative Bank has quantified just how much more interest it has received from new customers. The lender saw a 43% increase in customers switching from other banks in mid-2012, as scandals such as the Libor-rigging affair afflicted the country's banking industry. The Co-operative Bank has also distinguished itself for its acquisition of 632 branches and 4.8 million customers from Lloyds Banking Group, which was forced to divest operations following its government bailout. Following the takeover, the Co-operative Bank will have a market share in the UK of about 7%.

The Co-operative Bank has total assets of £50bn ($81bn), and as is the case with Rabobank in the Netherlands, it is its country’s only co-operative group. In France, there are three large groups – BPCE, Crédit Agricole and Crédit Mutuel – with co-operative businesses, which have €398.7bn, €315.6bn and €257.6bn in deposits, respectively. Germany has the largest number of co-operative banks in Europe; its 1111 institutions have average assets of €650m.

The new buzzword in the co-operative space is ‘biodiversity’, and indeed co-operatives certainly do not lack diversity with their various structures and sizes. “The co-operative ownership model is no constraint to the size of the bank,” says Barry Tootell, chief executive of the Co-operative Bank. “Our strategy is not to grow for the sake of growth. We want to strengthen and broaden our reach to our members and customers in the UK.”

Profitability for the Co-operative Bank and the European co-operative industry as a whole has been good, too. While European shareholder banks have had a compound annual growth rate of 1.2% between 2007 and 2009, and 1.2% between 2009 and 2011, co-operative banks recorded rates of 7.1% and 2.4%, respectively. Average gross revenues and total asset growth have also been less volatile for co-operatives during the crisis.

Addressing market failures

The history of many co-operative banks can be traced back to the 19th century, when most of these institutions were established based on the ideas of German economists Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch and Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen. They were built to serve rural communities and small businesses, which would have been cut out of banking products otherwise. The co-operative model addressed market failures, with the banks' members owning and financing the institutions, as well as helping to make strategic decisions. The community relationships and the member-ownership structure created incentives to ensure timely repayments of loans and allowed co-operative banks to grow.

The alignment of lender and customer interests has remained integral to the co-operative model. “Co-operative banks can’t go against the interest of their members,” says Sergio Gatti, director of the Italian federation of co-operative credit, Federcasse. “A co-operative bank would hurt its balance sheet rather than hurt its customers’ balance sheet,” he adds.

It may be for this reason that, historically, co-operatives have operated with higher Tier 1 capital ratios than shareholder banks. This has changed now, however, as regulation has forced banks to strengthen their balance sheets and Europe's largest banks have an average Tier 1 ratio of 12.2%, compared to the average for co-operatives of 10.7%, according to research by Oliver Wyman.

“In Germany and the Netherlands, we have seen that co-operative banks were able to make up [investment] losses because they were highly capitalised and because of their [sound] domestic business,” says Bouke de Vries, head of financial sector research at Rabobank.

According to Mr Hofmann at BVR, another reason for co-operatives' strong performance throughout the crisis was that such banks did not hold as many Portuguese, Greek, Italian or Spanish government bonds as other banks. As a result, they have gained favour in the public sphere. “Market sentiment, the sentiment of the public at large and of politicians is very much in favour of co-operative banks," he says. "At the same time, co-operative banks can’t isolate themselves from certain factors, such as the overall financial and sovereign debt crisis.” Mr Hofmann is, however, concerned about the low interest rate environment which now poses a threat to co-operative lenders.

Good judgement

Close knowledge of the local market and willingness to continue financing customers, even in tough economic times, has meant that co-operatives have continued to lend. Yet throughout the crisis, the percentage of non-performing loans in the total loans of co-operatives typically remained half that of the shareholder banks. “Part of the co-operative model is that people that work in the bank are willing to be held accountable,” says Mr de Vries. “Their internal governance system works very well.”

Being outside of the listed company structure also means that there is no quarterly pressure on financial statements and management can have greater flexibility in pursuing longer term goals. But the ownership and management models are not without faults. Lack of pressure on cost efficiency, which shareholders would typically exercise on management, is often cited as a negative. So too is the lack of specific banking knowledge, with the co-operative members who influence the bank’s strategy coming from a number of professions that may be far from the fields of finance or economics. This, and the large consensus process, can delay reaching decisions – or, as some critics fear, lead them to come to the wrong ones.

Co-operatives themselves are aware of such issues, but believe that the benefits of a ‘community’ consensus outweigh the negatives. “You do educate those [members] to understand economies, finance, governance and management of the business,” says Monique Leroux, chief executive of Canada’s largest financial co-operative group, Desjardins. “[The co-operative model] brings in a perspective on financial implications and democratic implications. You need to like it; it’s not the typical banker kind of thing. You need to have commitment to that, you need to accept that you have elected officers who may not necessarily be perfect but will have good judgement.”

Rough regulation

While the general public and politicians, including European internal markets commissioner Michel Barnier, are acknowledging the benefits of the co-operative model, regulators are not. Despite some modification to incorporate co-operative banks into Basel III calculations, the industry laments a lack of interest that can potentially be destructive to the sector.

"If you look at Basel III, with regards to the treatment of co-operative shares as core Tier 1 capital, it is only a footnote," says Hervé Guider, general manager of EACB. He does acknowledge, however, that some progress has been made at European level. "Co-operative banks contribute to stability, they fund the real economy," he says. "But regulation is designed at the international level and is based on the listed bank model and a one-size-fits-all principle. The Basel Committee is formed by 27 countries and there are only nine European countries [within it]. The challenge for us is to convince regulators outside of Europe to take into consideration our specific concerns."

It is not only regulators in North America that Mr Guider believes need to be convinced, but also those in emerging markets such as India, China, Russia and Latin America. In these countries the image of co-operative banks might be tainted by previous management failures. "We have to help regulators in these countries to understand about key success factors of the 4000 co-operative banks in Europe," says Mr Guider. "There are more than 2000 co-operative banks in India and they can [provide the answer] to the country's financial inclusion needs."

Different rules?

One implication of a heavier regulatory burden, however, is that smaller co-operatives could crumble under the weight of increased compliance costs and if not forced to merge, they may just find themselves out of the market.

“If a merger between banks, including co-operatives, can be justified for strategic reasons, it cannot be justified because of regulation. It is a market distortion; for us this is unacceptable,” says Mr Gatti at Federcasse. “There has been more interest from the academic world, more interest from savers when they are well informed, but no coherent attitude from regulators. After having recognised the higher resilience of co-operatives, the regulator, when it writes rules, does not consider this. The regulator seems to forget that the same rules for different entities do not achieve its objectives. They even disincentives or hurt banks that have a legal shape, size and business type different from international banks, which need regulation and are those that have created big systemic risks.”

BVR’s Mr Hofmann says: “There is a constant struggle between diversity and uniformity. If you have centralised solutions in terms of regulation and supervision, then they tend to strive for uniformity, while we would tend to say that we are a decentralised network of co-operatives, we strive for diversity. If you want to be simple in terms of regulation and efficiency, at least in the eyes of the [European] Commission, you strive for maximum uniformity, you don’t want exceptions. If you want to maintain diversity you have to look closer into business models and therefore differentiating regulation.”

There is also a worry that higher compliance pressures will go against ad-hoc decisions based on particularly close knowledge of individual customers. “We have lots of knowledge in the SME sector,” says Mr de Vries at Rabobank. “I think it would be a mistake to over-regulate the procedure of granting credit to SMEs because advisers would become risk-averse, so will grant less credit at a time when we need more.”

Gaining traction

If local values are being rediscovered in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the need to meet international regulations cannot be ignored. This is an area in which the vast majority of co-operatives can improve, and efforts are being made to enable such lenders to speak in a unified voice.

“[Co-operative banks] have had no lobbying power until now,” says one expert. “When you talk with the European Commission you hear ‘well, you’re fine, but the 18 co-operative banks [we spoke to] all say different things from one another – how can we manage with that?’.”

In an effort to bring lenders together, and generate more interest in their model, a series of initiatives such as the United Nations declaring 2012 the International Year of Co-operatives were launched, with support from governments and organisations from across the world, from Canada to Russia to Mongolia. But Mr Hofmann says that what the sector needs is to become zeitgeist of the post-Lehman era.

It may well be that the failures of capitalism are pushing the co-operatives’ spirit of solidarity in that direction. At a meeting of development banks a couple of years ago, when attendees were asked to stand at opposite sides of a room according to whether they thought banks’ stakeholders should also be shareholders, only one chief executive moved promptly to the ‘no’ side. “My mother has a bank account; I don’t think she should have a say in the bank’s strategy,” he said. This may not be the predominant view any longer, but co-operatives may need to push harder on the debate about why member-owned banks are worth having.