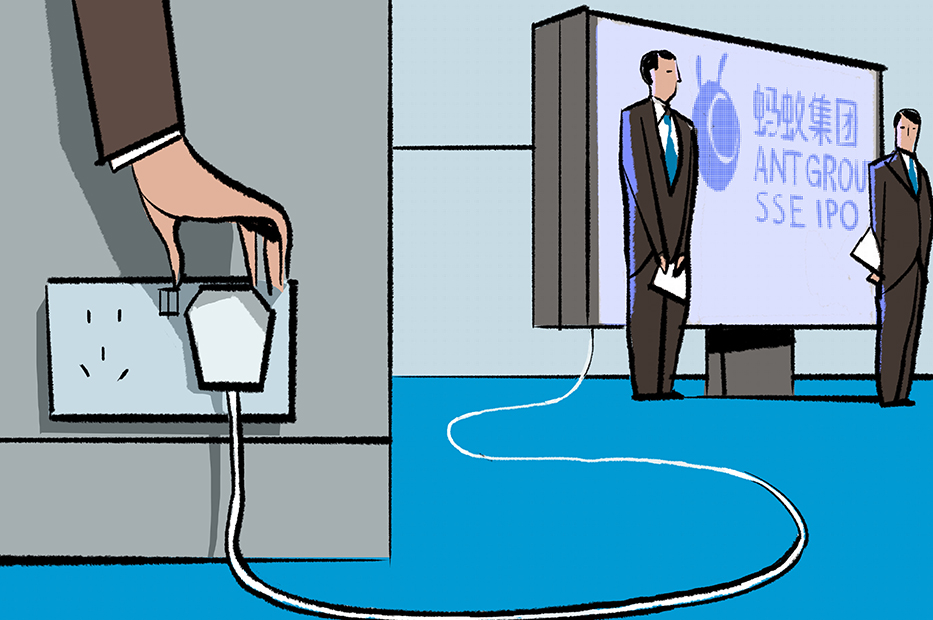

Ant’s IPO halt marks shift for China’s fintech scene

Alibaba affiliate’s suspended $35bn listing points to increase in scrutiny from Chinese regulators over fintech companies. How will the new rules impact the sector’s growth?

It was supposed to be the biggest initial public offering (IPO) ever. Ant Group was to launch simultaneously on the Hong Kong and Shanghai stock exchanges on November 5, 2020, with a listing of $37bn. The IPO had seen huge interest since its filing on August 26, seeing a record $3tn in bids for shares from retail investors. It was to far exceed the $29.4bn IPO by Saudi Arabia’s national oil company, Saudi Aramco, when it began trading on the domestic Tadawul stock exchange in December 2019. Listing Ant Group in China should have been a long-awaited, and highly feted, market event.

However, only days before it was due to launch, the Chinese regulator brought the IPO to an abrupt halt. On November 2, regulators called in Jack Ma, Ant Group’s controlling shareholder and owner of parent company Alibaba, Ant’s executive chairman, Eric Jing, and CEO Simon Hu for a closed-door meeting. On the same day, the regulators published new draft regulations specifically for China’s sprawling microfinance sector.

The process had seemed much simpler when parent company Alibaba launched its own IPO in New York in 2014. Mr Ma had been on hand that time to ring the bell, marking the arrival of his company’s $25bn offering. Instead, Ant Group was left with a last minute cancellation and uncertainty around if and when it would be permitted to list in China.

Stopped in its tracks

The news was an unexpected setback for a company that has seen exponential growth since the inception of Alibaba in 1999. Alipay, the payments branch of Ant Group, boasted 1.2 billion users internationally at the beginning of 2020, with ambitions of reaching two billion users within the next decade. During the November Singles’ Day (an unofficial Chinese holiday celebrating people who are not in relationships) shopping festival season, Alibaba racked up sales of $74.1bn across 11 days.

Through his position as founder and executive chairman of the Alibaba Group, Mr Ma has amassed a personal fortune of $60.5bn, according to Forbes, which named him China’s richest person in November 2020, and the 17th richest in the world. The suspension of the IPO shaved $2.6bn off Mr Ma’s wealth almost overnight.

The regulations are aimed, in part, at levelling the playing field between online microloan companies and other financial institutions regulated by the CBIRC

As investors were left reeling at the news, questions arose about why the decision was made. Some speculated that Ant Group was running the risk of becoming too big to manage. And stopping the IPO may well have served as a timely reminder of where the real power lies in China. Mr Ma had raised eyebrows only days before the suspension when he made a comment during a speech where he questioned the lack of risk in the Chinese financial system. “To innovate without risks is to kill innovation. There’s no innovation without risks in the world,” he said.

But any restrictions on the huge internet lenders is more than a straightforward reassertion of power. The China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) and the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) announced the joint Draft Interim Internet Microlending Governance Rules on November 2, 2020. The rules would stifle the growth of Ant’s consumer and small and micro lending business, which accounted for around 39% of the company’s first half 2020 revenue, according to Standard & Poor’s (S&P).

The companies targeted by the new rules offer small, unsecured loans and are not able to take deposits. They were initially given licences to operate by local financial bureaus, and provided far greater freedom in their operations than traditional financial institutions. The new rules will, in some respects, make a more level playing field across the financial services landscape. The banks, for example, already have to provide capital contribution to their unsecured consumer lending business.

What the rules mean

The draft rules will considerably constrain the business of China’s microlenders. They will now be restricted in cross-provincial lending, with a limit placed on the maximum loan amount and a minimum 30% capital contribution to joint borrowing.

In a statement, Liang Tao, vice-chairman of the CBIRC, said that “any listed company must comply with the requirements of relevant laws and regulations”.

“We encourage the financial sector to explore reasonable innovation while [keeping] risks under control,” Mr Liang added. “At the same time, we will regulate fintech in accordance with its nature of finance, and include all financial activities into the regulatory framework.”

The new regulations will have a significant impact on how these companies operate. They were able to operate unencumbered and acted as a conduit for other banks to lend. Ke Yan, lead analyst at Asia-Pacific-focused DZT Research, says: “In the past, it was possible to package loans as asset-backed securities or sell them to the bank, but now microlenders are required to put their own money forward to finance these loans.”

Therefore, they will be required to hold significant stores of capital. Mr Ke explains: “The regulation provides more details for online microfinance, and will raise the capital requirement substantially for online microfinancing companies. It requires Rmb5m ($765,000) as a registered capital, in real funds that can be paid out. That’s a very high capital requirement.”

Fear of contagion was a key component in the move to greater regulation. Katie Chen, director of financial institutions at Fitch, says: “We believe the regulations targeting licensed online microloan companies aim to contain risk associated with the rapid build-up of their activity and target a less regulated sub-segment of the Chinese consumer-lending industry that uses new technology, like fintechs, to offer microloans via online channels.

“The regulations are aimed, in part, at levelling the playing field between online microloan companies and other financial institutions regulated by the CBIRC.”

However, complying with tighter rules could be disastrous for the sector. Fern Wang, director at S&P Global Ratings, says the rules hit the company squarely in its business model. “Ant Group does not need much capital commitment to run its consumer-lending business, as it only retains on its balance sheet 2% of the total outstanding credit balance on loans it has originated; the rest, 98%, are offloaded on investors via structured finance products or on commercial banks that are keen to expand their exposure to consumer finance. Some 80% of loans originated by Ant Group are to retail customers, totalling almost Rmb2.1tn as of the first half of 2020.”

The changes will hit many fintechs’ ability to generate profits. “Regulators have also implemented a centralised payment clearing system called NetsUnion to contain settlement risk among payment companies,” says Ms Wang. “Third-party payment services, such as Alipay and WeChat Pay, now have to deposit 100% of their clients’ funds with PBOC and can no longer earn interest on those deposits.”

While the new rules will be difficult for the fintechs to stomach, they will not be introduced overnight. Mr Ke says: “The current regulation is very tight already, [but this is] putting fintech companies running a credit business on a level playing field with the financial institutions. There will be a three-year transition period for the fintechs to comply with the new regulation.”

Lessons from the past

The arrival of greater regulation should not come as a surprise, and many question why it has taken this long to be introduced. China has moved before to curb the growth of new financial institutions before they become too big to manage. Yu’ebao, a money market fund under Ant Group, had become the largest in the world by 2017. However, the regulator stepped in and forced individual investment levels to be capped at Rmb500,000 — around half the previously permitted total. Ms Wang says the size of the fund “raised the spectre of liquidity shocks in the event of mass withdrawals. The subsequent regulations on money market funds have constrained their growth.” Yu’ebao is now smaller than funds held by US-based institutions JPMorgan and Fidelity.

Similarly, the country’s peer-to-peer (P2P) lenders were also hit with stringent regulations, which Ms Wang says was down to concerns over “predatory lending”. However, these rules have effectively killed off this form of finance. “CBIRC indicated that there’s effectively no P2P lenders left in China now, compared with the peak of over 7,000 such companies before the rules took hold,” Ms Wang says.

Third-party payment services, such as Alipay and WeChat Pay, now have to deposit 100% of their clients’ funds with PBOC and can no longer earn interest on those deposits.

These might not be the last of the rules rolled out for fintechs, with the regulator warning it is keeping a close eye on their business model. Guo Shuqing, chairman of the CBIRC, said in a speech in early December 2020 that some tech companies “operate cross-sector business with financial and technology activities under one roof. It is necessary to closely follow the spillover of those complicated risks and take timely and targeted measures to prevent new systematic risks.”

Mr Guo added: “Fintech is a winner-take-all industry. With the advantage of data monopoly, big tech firms tend to hinder fair competition and seek excessive profits.”

Indeed, the regulator has stepped up to fine fintechs for past indiscretions. During December 2020, it was announced that Alibaba, along with Tencent-backed China Literature and logistics group Shenzhen Hive Box, had been fined for not obtaining regulatory approval for deals that had been made as long as six years ago. Issuing fines of Rmb500,000, the State Administration for Market Regulation gave a clear warning, stating that it wanted to “send a signal to society of strengthening internet antitrust law, to dispel the attitudes that some companies have — that they can wait and see, and enjoy flukes of luck”.

Systemic risk

In addition to concerns that these companies were becoming complacent, some of the move towards greater regulation comes from the fear of that these providers are becoming a systemic risk.

Robert Le, emerging technology analyst at capital markets data provider PitchBook, says: “Fintech companies have enjoyed a relatively light-touch regulatory environment for years, being able to provide a wide swathe of financial services without needing to have leverage or capital requirements like banks. Some of these fintech companies are now so large, with hundreds of millions of customers and large capital flows through their systems, that the Chinese government fears that financial instability [could ensue] should one or more of these companies fail.

“There are many risks; the failure of one of the top fintech companies could cause a domino effect industry-wide,” Mr Le adds. “Other risks include consumer over-borrowing; light criminal activity monitoring, such as money laundering; or various predatory practices, for example selling incorrect life insurance policies.”

The size of these internet lenders has caused the regulators to worry about the scale of consumer lending in China. Ms Wang notes how the P2P companies were regulated following concerns of predatory lending, while the new rules are aiming to scale back excessive levels of consumer borrowing.

Ms Chen adds that more stringent regulation is also increasing consumer protection. “The move forms part of a toughening of the government’s ongoing regulatory approach towards large internet conglomerates, which has also focused on issues such as data privacy and monopoly power. It points to concern among regulators about the risks posed by the online microloan industry and potential misalignment of risk incentives.”

While the established fintechs grapple with adapting the regulation, it may stop others from even entering the market. “The proposals will increase barriers to entry in the sector and larger players are better positioned to meet the requirement, which could lead to industry consolidation over time,” Ms Chen says.

The new regulations are unlikely to be the last of the changes the regulators introduce. “While pro-innovation, Chinese regulators’ top priority remains financial stability,” Ms Wang says. “We expect the Chinese government will continue to update its regulatory framework and guidelines to balance growth and risks in the rapidly evolving fintech industry, which we believe has been the policy trends for the past few years.”

Will Ant Group IPO again?

Halting the IPO sent a shock through the global markets, and had an immediate impact on the perception of Ant Group and its parent company Alibaba.

“The day after the announcement of the suspension the share price of Alibaba dropped by HK$22.60 ($2.92), or 7.5% based on the closing price of the second day, versus the day of the announcement,” Mr Ke says. “That is equivalent to about $63bn off the valuation for Alibaba, just because of the suspension of the Ant Group IPO.”

As well as new regulations affecting how it is able to operate, Ant Group will likely have to make changes should it move towards IPO again. Wei Hongxu, researcher at Beijing-headquartered independent think tank Anbound, says: “The new rule on online lending does have a huge impact on Ant Group, especially for the credit business, either by replenishing nearly Rmb100bn of capital to meet regulatory requirements, or by divesting the microlending business and reform as a financial retail platform, but this also means that Ant’s profits will be significantly reduced, which will affect valuation for an IPO.”

Mr Le says the suspension will significantly slow down or even stop Ant Group’s expansion plans into new business areas and markets. “Without the expected [$37bn] windfall raised from the IPO and shifting resources and focus to regulatory compliance, growth for the company will slow down next year,” Mr Le says. “The new capital requirements could also diminish the nearly $290bn, according to Goldman Sachs’s estimate, in consumer loans that the company is expected to issue next year, which will be reflected in slower revenue growth. Because of this, the company’s valuation, and the amount they can raise in a future IPO, will be lowered as investors take into account reduced top-line growth and new regulatory risks.”

Should Ant Group move towards another attempt at IPO in future, the likelihood is that it would be scaled back from what was seen in November. Mr Ke says: “As this limits the business prospects of Ant Group in the short term, it will lower the value of another attempt at listing next year.”

The move will also impact investors looking to use the IPO as a benchmark for the valuation of these huge online lenders. Mr Ke says: “Investors in Alibaba were expecting the IPO to crystallise the value of the fintech business. With the Ant Group IPO suspended, then the valuation of Ant Group and Alibaba becomes vague.”

However, others argue the suspension will help to bring a sense of perspective to the valuations of companies in this still relatively nascent financial sector. Mr Wei says: “There have been some doubts about Ant Group’s high valuation, and they are now accepted by most investors. Such change has also reduced the investors’ enthusiasm for technology stocks.”

The move could ultimately impact on how willing other companies, both domestic and international, are to list with a Chinese bourse. “We believe that the constant regulatory flux in China could scare away investors from investing in Chinese companies,” says Mr Le. “Also, companies looking to list publicly could choose to list on foreign stock exchanges versus those in Shanghai or Hong Kong.”

But with this in mind, China and Hong Kong’s stock exchanges saw their most active year in 2020 since 2011, according to KPMG. Shanghai Stock Exchange combined with Shenzhen Stock Exchange is expected to see an 82% uplift in funds raised compared with 2019, reaching Rmb461bn from 383 new listings. Further, Hong Kong’s bourse has seen a 24% increase in funds raised, hitting HK$389.9bn from 140 IPOs. The boost in activity in Shanghai and Hong Kong contributed to a 23% increase in proceeds raised in the global IPO market in 2020. The Chinese stock exchanges are unlikely to be too concerned by a drop in business just yet.