Can the oil industry's creditors take the strain?

The commodities rout is claiming a growing number of victims. But are leveraged loans, and the banks that fuelled the US oil shale boom, among them? Danielle Myles investigates.

For US oil companies, the heady days of mid-2014 must feel like a distant memory. Prices hovered around $105 a barrel, borrowing costs were low and drilling technology had been fine-tuned to bring down break-even points.

Fast-forward to April 2016 and it is difficult to overstate the problems facing the industry. The benchmark WTI crude oil price has dipped to a 13-year low of $27 and even the biggest and most diversified oil companies – including Chevron – have seen their debt ratings downgraded.

Forty-two upstream petroleum companies have filed for bankruptcy protection since the start of 2015. Ken Buckfire, managing partner and founder of investment bank Miller Buckfire, expects dozens more to restructure or default by the end of this year. “The problem is that all these companies that created their balance sheets up to 18 months ago were pricing on a forward oil curve of $80 to $100 a barrel. No one was expecting a price collapse of 70%,” he says.

The smaller developers behind the shale boom have been working on a model of high debt to Ebitda (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation). But even moderately leveraged producers have – as a result of Saudi Arabia’s steadfast refusal to curb production – suddenly found themselves highly leveraged. These businesses are clearly facing tough times, as are their subordinated, unsecured high-yield bondholders. But what about the $205bn of leveraged loans that, according to Dealogic, remain outstanding in the upstream petroleum sector?

While the banks that originated these loans may have kept a small portion on their books – particularly when acting as a relationship lender – the capital charges for holding highly leveraged debt are so steep that the majority has been distributed. As such, the aftermarket is a good barometer of the asset class’s health.

Secondary markets absorb the pain

As of the end of January, Fitch’s default rate for institutional leveraged loans to the energy sector was 9.8% – well above the 2.2% average, and it was set to rise again. “It is fair to assume that by the end of the year it will be higher than the 9.8% we saw in 2015,” says Sharon Bonelli, senior director of leveraged finance at Fitch.

Based on deals tracked by the Loan Syndications and Trading Association (LSTA), total returns for oil and gas in 2015 were -29%. Ted Basta, senior vice-president at LSTA, says that the sector has traded down substantially, right alongside the price of oil. In June 2014, the average bid was more than 100 cents on the dollar. Five months later it was 92 cents and as of February 2016 Mr Basta says it was in the 60s.

These figures are, no doubt, alarming. But they must be considered in the context of the oil sector’s typical funding model. Most non-investment-grade producers rely on bonds, coupled with a revolving credit facility that stays on the original lender’s books. So while the oil and gas sector represents about 17% of US high yield, it accounts for only 4% to 5% of loans in the secondary market.

Such a small segment is not expected to pose a risk to the market as a whole. Indeed, at the end of February the average bid across the US leveraged loan universe was 90 cents, with a median of 96.75 cents. It also creates a ceiling on the number of oil loans that can become stressed. “Given the sample is smaller than high-yield bonds, there are only so many names that are going to default when all is said and done,” says Eric Rosenthal, senior director of leveraged finance at Fitch.

While this mitigates the possibility of systemic risks, those holding the 4% to 5% loans with direct exposure to the oil crisis also have some factors working in their favour.

Silver linings for lenders

First, and most importantly, as these are senior secured loans – and typically first-lien – they have the safest position in the borrower’s capital stack. Historically, the loss content on this debt has not been high.

Mr Buckfire, whose career has spanned four oil crises, is confident that first-lien debt-holders will be paid out in a default, restructure or bankruptcy. “They will be fine no matter what. It is just a question of whether they are prepared to roll over into a new loan or whether they will ask to be paid off, meaning the company must find someone else to lend them first-lien money.”

If this debt is so safe, it raises the question of why it is trading at such a heavy discount. According to Mr Buckfire, it is not because there is any doubt about the underlying credit or getting repaid at par, but because on a relative basis they are mispriced. As many of these loans were issued during the high-yield boom two to three years ago, their coupons were set at low spreads over Libor. An equivalent loan – subject to the same risk – issued more recently would have a higher interest rate. So anyone buying these older loans will want a significant discount; not because they do not think they will get repaid, but because the return is small when compared with the opportunity cost of other investments.

While this bodes well for creditors willing to hold the paper until maturity, those wanting to sell may not recover the discount seen in today’s trading prices until the oil sector’s health significantly improves.

The second factor working in loan-holders’ favour is that banks, mutual funds, hedge funds and other investors are required to periodically mark these loans to market. This means the risks have been managed transparently and, sources agree, a lot of the pain stemming from the oil collapse has already been absorbed and reflected in loan values.

Third, many of today’s loans were refinanced before 2015, and were given five- or six-year terms. “They were pushed out for the most part to 2018 and beyond, so this and next year are relatively light in terms of maturities,” says Michael Paladino, head of leveraged finance at Fitch. Data from the rating agency shows that $500m of energy leveraged loans mature this year. Next year it is $200m, before jumping to $6.2bn and $4.2bn in 2018 and 2019, respectively. “That is giving them some cushion. If that were not the case, the situation would be even more acute,” says Mr Paladino.

Finally, exposure is likely to be spread across a broad cross-section of investors. Given the secondary loan market is private, it is difficult to identify exactly who is holding distressed debt. But anecdotal evidence suggests it is shared among a large number of collateralised loan obligations – which rarely hold more than 1% to 2% in any position – along with some banks and, inevitably, hedge funds and other distressed debt investors.

While common sense may suggest that opportunistic buyers are snapping up loans to struggling oil companies, Mr Buckfire believes otherwise. “There has not been as much trading in this paper as you would think,” he says. “For most vulture funds it is not very exciting – why would you want to go to all that trouble to buy a loan like that? So even though there is a price out there for this paper, there has been relatively little volume as there really is no natural buyer for it,” he says. Strategies built around enforcement are less common in this sector because what the investor would be left owning – oil reserves and drilling equipment – is more difficult to work with compared with the collateral used in other sectors.

Banks sidestep direct exposures

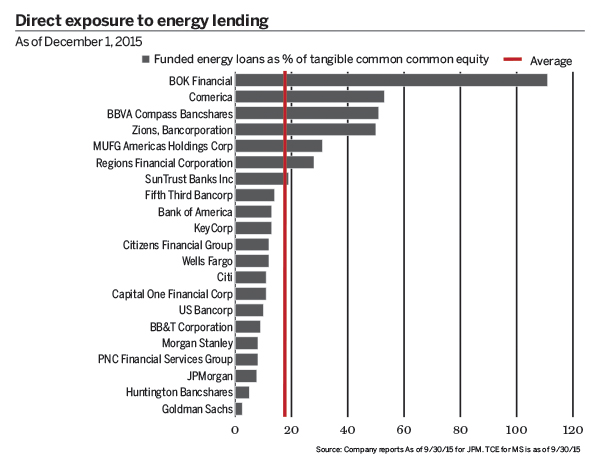

That most banks have distributed leveraged debt soon after origination is reaffirmed by data collected by Fitch (see chart). The vast majority of banks’ funded exposure to energy borrowers, both investment and non-investment grade, is fairly modest when compared with their tangible common equity. The amounts being put aside by the biggest banks to cover losses from this sector – including $500m by JPMorgan in February – have made headlines. While this may hit their results, the impact on their capital is manageable. “There may be even higher provisioning for loan losses in future. But, at this point, we think it is more of an earnings story,” says Justin Fuller, a senior director in Fitch’s financial institutions group.

The situation is different for some smaller, energy-focused banks, such as BOK Financial, that have a higher proportion of oil and gas loans on their books. “They have managed pretty well up to this point. But someone like them may have performance issues compared with the larger banks, which are diversified across the platform,” says Mr Fuller. BOK did not respond to The Banker’s request for comment.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) in the US has been criticised for being overzealous in prompting regional banks to move problem – but arguably recoverable – assets into their workout groups. While the regulator is naturally concerned about banks’ balance sheets, those that lend to oil companies understand the cyclicality of the industry and want to work with struggling borrowers, rather than push them into a premature bankruptcy filing. In an emailed response, an OCC spokesperson says the regulator encourages and expects banks to constantly identify, measure, and manage risk, and to address loan performance issues in their early stages and to work with borrowers to resolve problems whenever possible.

This friction will come to a head in late 2016 when regulators release the results of the Shared National Credits (SNC) review, the syndicated loan market’s annual report card. Last year’s review identified weaknesses in leveraged lending and oil and gas, and, according to Mr Fuller, it is fair to assume that this year regulators will prompt banks to downgrade more oil credits to non-performing status. That said, leveraged lending to oil and gas borrowers dropped to $79.8bn in 2015 – down from $113bn in 2014 – and, according to Fitch, the proportion of those loans that are covenant-lite is well below the average. Banks have the right to appeal against SNC recommendations, and a significant number are expected to this year.

Before banks’ SNC results are due, leveraged oil producers face their own test. Just like their term loans, these companies’ revolving credit facilities – often their primary source of funds – are secured by the proven value of their oil reserves. Every six months, US banks reassess this borrowing base and adjust the size of their exposure by, for example, reducing credit lines. This review, which is known as redetermination, is taking place over March and April.

Given that this calculation is based on current oil prices and the borrower’s hedging arrangements (many of which are rolling off this year), the cuts are expected to be severe. With the capital markets closed to these issuers, they are likely to need these revolving credit facilities now more than ever. It is this liquidity crunch that Mr Buckfire says will trigger the dozens of defaults and restructures that he predicts over 2016.

In the midst of a reset

For oil producers that survive these cuts, their leveraged loan-holders will be firmly focused on prices recovering to the point that projects can become profitable. Scotiabank has found the majority of US shale projects to have a breakeven price of WTI $45 to $55, while other analysts report that the biggest basins – the Permian and Eagle Ford – can break even at about $30 a barrel. However, for the sector as a whole to stage a turnaround, analysts say prices must reach about $45 a barrel.

Discrepancies in oil forecasts creates little comfort as to when this will occur. Predictions for 2016’s average WTI range from $32.75 (JPMorgan) to $55 (Citi), with many settling around $37. Few are expecting prices to stabilise at $45 until next year.

Some leveraged producers will be able to ride out the interim, but many will need to restructure their balance sheets. “If they are good operators with good properties they will survive; the only question is who will own them and who will provide the capital that will allow them to continue to drill,” says Mr Buckfire. The answer, according to several sources, is private equity firms’ distressed debt funds. After accumulating significant capital, many are waiting until oil prices stabilise before buying companies or their assets. Fitch’s Mr Paladino is watching to see how this shapes the default outlook.

The consensus is that the US oil sector is in the midst of a reset – which will take three to five years, based on the crises Mr Buckfire has witnessed. But while leveraged loans are trading at a heavy discount, they have neither caused, nor will suffer the bulk of the damage in the long run. If this helps restore the reputation of an asset class subjected to its fair share of criticism over the years, it may just be the commodity crunch’s silver lining.