The latest round of EU reforms has made bank capital structures even more convoluted. Danielle Myles unravels the new style of debt instruments that are set to grow into a €200bn-plus market.

In recent years, policy-makers in many Western countries have been fixated on avoiding a repeat of the taxpayer-funded bailouts needed after the global financial crisis. Their reforms have spawned new generations of loss-absorbing debt to be issued by the biggest banks. First was additional Tier 1 (AT1), which was sparked by Basel III. The latest category, which aims to satisfy the total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) standard, has an even more nonsensical name: 'senior non-preferred'.

This new breed of bank debt is being championed by the French. On December 11, 2016, France became the first country to enact a law recognising senior non-preferred debt. Two days later, Crédit Agricole opened the market with a €1.5bn deal, with Société Générale, BNP Paribas and Group BPCE quickly following suit. Within two months, they had collectively issued nearly €13bn.

New layer in the stack

The lenders have done this because, as global systemically important banks (GSIBs), they must hold TLAC – which includes regulatory capital – of at least 16% of their risk-weighted assets by 2019 and 18% by 2022. The European Commission’s (EC's) rule that implements TLAC across the EU, the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL), goes a step further by permitting national regulators to impose MREL on smaller banks and set higher targets for GSIBs.

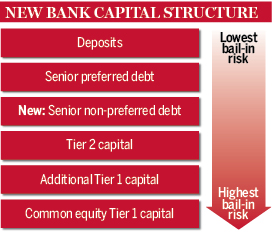

As a result, EU banks must now find a way to fill the gap between regulatory capital levels and MREL targets. This new layer in the creditor hierarchy, which sits above Tier 2 but below senior debt (now known as ‘senior preferred’), has two key criteria: it is unsecured, and it can be bailed in only after regulatory capital (Tier 1 and Tier 2) and only when the bank is so stressed that regulators have stepped in to restructure it.

Senior non-preferred (which is sometimes called Tier 3) is one way to fill this gap, but not the only way. Senior unsecured debt issued from a bank’s holding company (holdco) also qualifies as MREL, because it is subordinate to senior debt issued by the operating company (opco). UK banks have been building MREL (and Swiss and US GSIBs have built TLAC) like this for some time. Germany has created yet another solution. In 2016, it passed a law to split its banks’ outstanding senior debt into two categories: secured notes were pushed up the hierarchy, while the remainder were reclassified as MREL.

This new layer of bank debt will be huge. The European Banking Authority estimates that the MREL requirements of the EU’s 133 biggest banks are between €186.1bn and €276.2bn. If Swiss issuance is included, some expect the European market to reach €300bn. By comparison, today’s EU AT1 market is about €105bn.

Harmonisation attempts

To avoid a fragmented approach to MREL, and investor confusion, last November the EC encouraged governments to follow France and change national laws to create a senior non-preferred instrument. This reasoning has found support. “What you need is a US investor, for example, to not have to stop and think about different creditor hierarchies in different countries before buying this debt. Otherwise the risk is they decide it’s too much work, and so don’t invest at all,” says Giles Edwards, senior director at rating agency S&P. “The EC, to its credit, recognised that and has tried to lay the grounds for a generic asset class.”

While this makes MREL more harmonious than it could have been, Samir Dhanani, head of capital structuring, Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA), at Credit Suisse, says it is still not homogeneous because the other routes are still possible. “What we find ourselves explaining a lot is that whether it’s through a holdco, the French approach or the German approach, the endpoint is the same,” he says. “The risk to the bondholders is similar, and the bank is creating a new layer of debt that’s above their regulatory capital but below general obligations. It’s just that there are several ways to achieve that outcome.”

French lessons

Following the EC’s November announcement, more countries are expected to follow France, making the first senior non-preferred deals instructive on how MREL debt will take shape. Structures have been, and are expected to remain, relatively simple. This is partly because of MREL’s strict eligibility criteria, which include a ban on coupon deferrals, derivatives and waivers of set-off, and a minimum one-year tenor requirement.

But this simplicity also reinforces the fact that MREL is a senior instrument. UK banks have issued senior holdco notes callable one-year from maturity (once it becomes ineligible as MREL). However, the first senior non-preferred deals have avoided call provisions which, bankers note, are historically associated with subordinated debt. “By going for a vanilla trade, you anchor your bond in the senior world. This was one of the issuer’s objectives; making it simple, clear and as close as possible to the classical, senior unsecured transaction,” says Bernard du Boislouveau, head of financial institutions, debt capital markets (DCM), Paris, at Crédit Agricole Corporate & Investment Bank, referring to the bank’s debut deal.

For issuers, this improves pricing. Senior non-preferred has priced closer to senior-preferred (30 basis points to 50bps away) than Tier 2 debt which, according to bankers, indicates that investors understand it can only absorb losses in very rare scenarios. Spreads are expected to tighten as it becomes a more established asset class. “At some point the European banks will want to achieve a premium that is as close as possible to the US banks, which is 20bps to 25bps,” says Khalid Krim, Morgan Stanley’s head of European capital solutions. “For banks with larger needs and bigger volumes to raise, I think that will take a bit of time, probably when they are refinancing their first round of MREL deals.”

Currency and investor diversification

Of France’s nine senior non-preferred deals to date, four were in euros, three in US dollars, one in yen and one in Swedish krona. More currencies are expected in response to buy-side demand and, in the case of Société Générale, in line with group-level polices to diversify its investor base. “We are doing this with preferred senior debt and Tier 2 debt, and it’s what we intend to do with senior non-preferred,” says Vincent Robillard, the bank’s head of group funding and collateral management. “Obviously the euro and dollar markets remain our two major markets, but as long as the price is consistent with those two curves, we intend to take advantage of the interest expressed in other regions and currencies.” Indeed, the bank’s krona deal was spurred by reverse inquiries.

Crédit Agricole has a regular presence in Japan, having issued senior and Tier 2 yen-denominated debt. Global head of financial management Olivier Belorgey says the group will join BPCE in issuing yen-denominated senior non-preferred debt and look at other currencies as opportunities arise.

Deals have been oversubscribed, some up to 3.5 times, and buyers are a mix of Tier 2 and senior debt investors (for whom the bonds offer a yield pick-up). In the euro deals, orders came from a broad mix of countries. In Société Générale’s €1bn deal France represented 30% of allocations while German-speaking countries took 16%, the Nordics 11%, Benelux 11%, UK and Ireland 10%, and Italy 9%.

The alternatives

The EC’s encouragement of senior non-preferred debt does not stop banks issuing holdco senior to satisfy MREL. This is a much simpler process, but aside from those in the UK, only a handful of continental banks are set up with a holdco and therefore have this option. They include Belgium’s KBC, which raised €1.5bn via two senior holdco deals in 2016, and Dutch majors ING and ABN Amro. The former has announced it will take a holdco approach, but it seems ABN Amro will break rank. Its fourth-quarter report for 2016 states it "expects to potentially" sell senior non-preferred debt from its opco, from which it has issued its other capital and debt instruments.

The EC’s guidance of national governments towards France’s approach does, however, create a predicament for Germany. The country’s decision to change its laws to recategorise a large chunk of outstanding senior debt might have brought many German banks above their MREL targets well ahead of the deadline, but some query whether authorities must now create a framework to allow banks to issue MREL debt going forward.

S&P senior director Richard Barnes expects some clarification over whether banks can issue vanilla bonds that count as either senior preferred or senior non-preferred debt. “If that were to occur, going forward their banks would be in a similar position to French banks in that they could issue one or the other,” he says.

Santander’s solution

Banks with neither a holdco nor a national framework such as France’s or Germany’s have no clear path to meeting MREL. Santander, however, has pioneered a solution that is expected to be followed by others. In February it issued a €1.5bn senior bond which is contractually subordinated to its outstanding senior debt. Once Spain passes a law recognising senior non-preferred debt – as has been expected for some time – the bond provisions automatically flip into compliance with the statute.

Vincent Hoarau, head of Crédit Agricole CIB’s financial institutions group syndicate, thinks it unlikely that legislation will be approved elsewhere in Europe before the second half of 2017, making Santander’s deal, which was two times oversubscribed, a strong precedent. Morgan Stanley’s Mr Krim adds: “The question for investors is whether there is enough visibility that they are willing to buy something that is the contractual equivalent to the legislative regime going forward. Investors are getting more comfortable with this, so more are saying yes.”

Mr Krim has had many conversations with other EU banks about doing something similar. Credit Suisse’s Mr Dhanani notes that whether a bank can replicate Santander’s solution is country-specific because it must be permitted under national insolvency law. But he expects a lot of GSIBs in particular will be looking at Santander’s deal closely as their first TLAC deadline looms in 2019.

Different approaches

MREL will be raised at the expense of other bank debt, but each bank will have a different strategy. ING intends to replace maturing senior debt with MREL notes, whereas Crédit Agricole and BPCE are planning to replace maturing Tier 2 debt. Market conditions and investor appetite allowing, Mr Belorgey says Credit Agricole hopes to have a roughly even split of senior non-preferred and Tier 2.

Making maximum use of senior non-preferred debt makes sense from a cost perspective, and because it can be issued with five- to six-year maturities. “For Tier 2 you must issue long term – most of the market is 10-year – but from a liquidity point of view our business doesn’t need this huge amount of very long-dated debt,” says BPCE chief financial officer Olivier Irisson. “It’s inefficient, particularly given that the cost of subordination is quite high.” Shorter maturities are also more appealing to asset managers, who typically don’t want 10-year debt.

An alternative theory is that senior non-preferred and senior holdco investors may be reassured if the issuer had a big Tier 2 buffer. “Would they get a pricing discount on that debt, compared with a similar bank which had nothing apart from AT1 and equity, because investors perceived a lower risk of default or were comforted that their loss-given default might be better? I think that is an open question and that banks will approach it in different ways,” says S&P’s Mr Edwards.

More open questions

French banks have laid the groundwork for a buoyant new asset class. But it will not all be smooth sailing. The EC recently proposed changes to MREL criteria which are inconsistent with TLAC.

“It rules out acceleration outside insolvency and winding up [whereas some UK holdco senior issuance permits this] and it requires a contractual bail-in clause,” says Mr Dhanani. “If the latter requirement remains, the question is how that’s worded – whether it’s an acknowledgement of bail-in, something more, or something less – and it is important because it can have meaningful pricing implications as investors may fear it might lead to [investor] losses beyond what you’d have in a statutory scenario.” Mr Krim adds that banks have thus far been prudent, amending provisions to make sure that they do not create any ineligibility risk.

Another difficulty is that banks still do not know their MREL thresholds, because they are being set on a bank-by-bank basis by national regulators. “When banks go to market, they need to be able to tell investors their issuance plan and describe what supply is going to look like. But they can’t communicate this as they don’t know how much they need to issue,” says Sandeep Agarwal, Credit Suisse’s head of DCM in EMEA. With 2017 shaping up as the year of senior non-preferred debt, answers to these questions are needed soon.