The sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone has had little impact on the euro’s exchange rate against the dollar. However, it has delayed the process of reserve diversification.

While spreads on peripheral eurozone debt soared in 2011 as fears of one or more sovereign defaults rose, the currency itself was strikingly resilient. The euro actually climbed against the dollar in the first half of the year, after the European Central Bank (ECB) hiked interest rates, and even the sell-off in the second half of the year still left the currency exactly where it started 2011, at about $1.29 per euro. Its moves against UK sterling were similar, with only the yen among the four major currencies appreciating significantly against the euro, as Japan’s vast savings pool repatriated assets.

Of course, the US has problems of its own. The Federal Reserve has engaged in two rounds of quantitative easing – expanding the money supply by buying US treasuries for cash – and a third was mooted during 2011. By contrast, even the ECB’s securities markets programme through which it bought the debt of troubled eurozone sovereigns is in theory neutral from a monetary policy viewpoint. The ECB sells deposits to mop up any excess liquidity created by bond purchases.

And even if treasury spreads have remained very low, both currency areas face fiscal challenges, as evidenced by the downgrade of the US sovereign rating in 2011 and the political deadlock over raising the government’s debt ceiling. In fact, the eurozone has arguably moved ahead of the US to address those budgetary risks.

“Choosing between the euro and the dollar is a bit like choosing between the flu or a stomach bug at the moment,” says Giulio Martini, chief investment officer of currency strategies at $406bn asset manager AllianceBernstein. “It is unprecedented for all four of the largest currencies to be unattractive at the same time; all really have the same problems of high private debt migrating to the public sector, driving stimulative monetary policy.”

Reserve status delayed

The fact that fiscal woes are widespread does not offer a great comfort to the most cautious of players in the foreign exchange (FX) markets – the central banks that need to allocate reserves in the good times for use in liquidity support operations in the bad times. As policy-makers themselves, central bankers may have been particularly shocked by the way the euro crisis played out.

“Both central bank reserve and sovereign wealth fund managers have been surprised at the passive, unconstructive stance of eurozone policy-makers in the early stages of the euro crisis. While the break-up of the euro is seen only as a tail-risk, this is still a significant change even from two years ago, when such a scenario would not have been discussed at all. And tail-risks have tended to play out in 2010 and 2011,” says Andrew Rozanov, managing director of institutional portfolio advisory at fund of hedge funds Permal in London.

When originally created over a decade ago, the euro was widely touted as a potential alternative for central banks that held the bulk of their reserves in dollars or gold and wanted to reduce the concentration risk. That pressure to diversify is still there, but the attractiveness of the euro as an alternative has clearly been tarnished, says Paresh Upadhyaya, US director of currency strategy at Pioneer Investments, a $209bn asset manager owned by Italy’s UniCredit.

“The most recent International Monetary Fund [IMF] surveys of central bank reserve holdings have shown the euro falling slightly as a proportion of the total, so I do not think it is likely that we will see its role in global reserves rise significantly at the moment,” he says.

In addition, the dollar still dominates in terms of financial transactions, including international financial market instruments and invoicing for cross-border trade transactions. Based on surveys by the Bank for International Settlements, the dollar’s share of such transactions has dipped from about 89% when the euro was launched as a settlement currency in 1999, but only as far as 84% today.

“The dollar is still the invoicing currency of choice, it enjoys network and scale effects. Most commodities trading and even most European exports to non-European countries are settled in dollars,” says Mr Martini.

However, central banks are also reluctant to accumulate much more in the way of dollar reserves, given that the US has problems of its own. This means that any phase of risk appetite that drives up commodity prices and inflows to emerging markets could also strengthen the euro on a mechanical basis. Emerging market central banks will need to buy euros just to avoid increasing the proportion of dollars in their expanding reserves – up from $5460bn at the start of 2010 to $6840bn in the third quarter of 2011, according to the IMF.

Lack of alternatives

This reserve accumulation highlights the core problem for the largest institutional investors active in the FX markets. The four major currencies are the only ones with asset markets large and deep enough to absorb significant investment.

John Nugee, senior managing director of the official institutions group at State Street Global Advisors (SSgA), says that many reserve managers have chosen to move funds between eurozone sovereigns, rather than out of the eurozone altogether. SSgA created a defence fund divided 40:40:20 between German, French and Dutch sovereign debt, which has seen strong demand.

“The analysis among the largest investors is that there are no deep alternative markets, and that a complete fragmentation of the eurozone is the least likely outcome. If weaker members leave, this would be positive for the residual euro. So the credit exposure to the eurozone must be managed, more than the FX exposure,” says Mr Nugee.

Mr Nugee says central banks are looking at emerging market government bonds as an attractive alternative to the eurozone periphery, as many emerging markets have low sovereign debt. But for precisely that reason, they also have limited financing needs, and it is not desirable for emerging market governments to meet the pent-up demand.

Chilean officials suggested recently that the country could cover its funding needs five times over, but has no intention of issuing on such a scale. Governments in South Korea, Brazil and Taiwan have all considered or taken measures to stem foreign inflows and currency appreciation.

Downside risks

While central banks are more constrained in the search for non-euro liquid assets, both sovereign wealth funds and private investors such as pension funds and hedge funds have broader alternatives. That does not necessarily mean exiting the euro. One banker recalls a conversation with a sovereign wealth fund manager who suggested that they would not buy Greek government bonds, but might consider buying debt issued by Athens International Airport if it had suitably predictable cash flows.

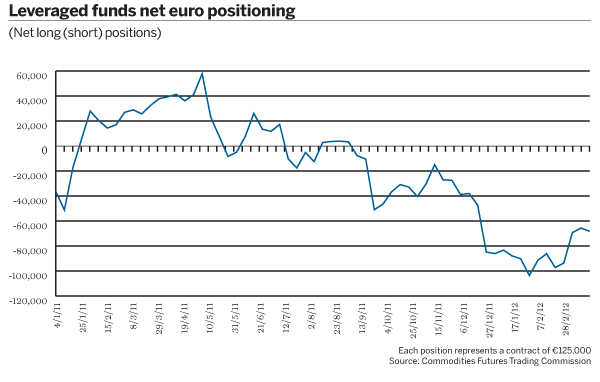

Nonetheless, there is a general consensus that downside risks on the euro are outweighing any upside potential for now. Athanasios Vamvakidis, European FX strategist at Bank of America-Merrill Lynch, says the peak of central bank euro selling occurred in the third quarter of 2011, when Italian sovereign access to the capital markets seemed to be in doubt. Those sales quickly abated once the ECB stepped in, but the heaviest euro short position among hedge funds was in the first two months of 2012.

“Since then, there has been a short squeeze supporting the euro, and positioning is more balanced. But that means many investors will need to increase their short euro hedging again if the crisis takes another turn for the worse,” he says.

Investors identify elections in Greece and France as potential flashpoints for policy changes that could unnerve the currency markets. Mr Vamvakidis sees limited upside potential for the euro in 2012, especially as the prospects for a fresh round of quantitative easing in the US appear to be receding as growth picks up. And the peripheral euro area countries need a weak currency to help economic recovery in any case.

Henrik Pedersen, chief investment officer at specialist currency manager Pareto Partners, says that eurozone investors themselves could engage in more diversification into other currencies. Fiscal austerity suggests low growth and ultra-low interest rates in the eurozone are here to stay. This is beginning to make the euro the funding currency of choice for carry trade investing in high-yielding currencies – a role traditionally played by the yen before the financial crisis.

“Ironically, that could make the euro behave as a safe haven on any risk reversals if European investors repatriate funds,” says Mr Pedersen.

The tightening spreads on certain peripheral eurozone government bonds, especially in Ireland, suggests that the periphery can begin to rebuild investor confidence with the right fiscal policies. But SSgA's Mr Nugee points out that central banks will always prefer to let private investors lead on any recovery trade.

“Reputation is everything to a central bank, it is key to monetary policy. There is no upside for them if they profit from getting in at the start of a rally, and plenty of downside if the calm turns out to be temporary and they suffer losses on their reserves,” he says.