Euro banks put up a fight for ECM deals

With block trades now commonplace and the pace of deals accelerating, the battle for European equity capital markets is getting tough. European banks will need smarts and stamina to survive. By Carol Dean.

What a difference a few years can make in equity capital markets (ECM). Gone are the days of heavily oversubscribed deals and heady aftermarket trading witnessed in the late 1990s. The going is tough for European ECM players and only the biggest and strongest among the banks are expected to survive.

And the reigning heavyweights are, without doubt, the US banks. In a hostile trading environment, US banks have put their sizeable balance sheets to good use in securing the majority of deals that have emerged in the past four years. Some argue that they have also steered the European ECM business towards the higher risk transactions that have helped to eclipse some of the competition.

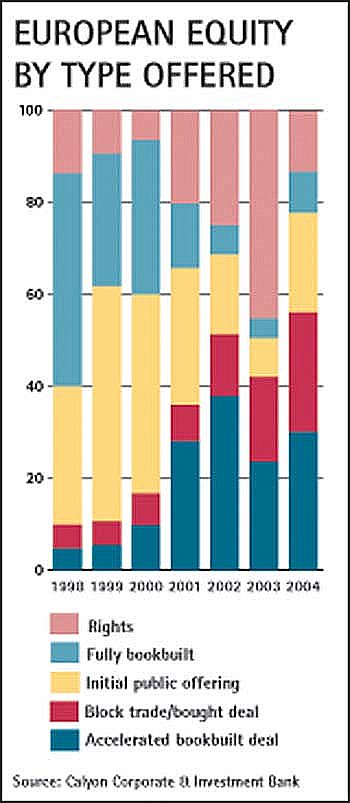

Block trades (bought deals, in which the underwriting firm offers a firm commitment to purchase the entire issue from the issuing company) and accelerated book built transactions that were rare in the 1990s are now commonplace in European ECM. Aggressive, fast track and highly competitive, these deals have shifted the cost of execution on to the arrangers’ shoulders.

Figures produced by data provider Dealogic reflect that in the past five years the use of accelerated/bought deals has increased in Europe compared with fully marketed transactions. According to Dealogic, 145 accelerated deals were completed last year on behalf of European issuers compared with just 22 in 1999.

French investment bank Calyon estimates that bought deal and accelerated transactions accounted for 56% of the total value of deals done in 2004. All secondary issues or follow-on offerings were done on an accelerated book built basis, apart from the Italian government’s €8bn sale of a stake in utility ENEL, which was fully marketed to entice retail investors into the deal.

Just as importantly, many bankers argue that the degree of risk has also increased depending on the type of execution adopted. Under the bought deal structure, the arranging bank uses its balance sheet to bid for a block of shares in a competitive auction and holds them until they are sold in the market. Another type of execution involves accelerated book building where the bank receives a commission for acting as an agent for the seller. The bank will rapidly build a book, price the stock accordingly and place the shares with investors.

There are also hybrids of the accelerated structure. One hybrid that is becoming increasingly common – which was first adopted by the French government in the sale of France Telecom stock in September 2004 – involves banks providing a backstop, or minimum guaranteed price. The bank and the seller share in the upside if the stock is priced above the minimum but the bank bears the loss if the price obtained falls below the backstop. Sometimes banks are paid a commission for providing this guarantee.

Unquantifiable losses

Investors have increasingly good access to market information and this, too, is slicing into ECM margins. Just as banks will be aware of when lock ups (the standard time period during which governments and corporates agree not to sell any more shares after a sale, usually six months) are due to expire, so too will institutional investors’ appetite, as they will be looking for an attractive discount on the stock. This puts a lot of pressure on the price that sellers – and arrangers – can get for a stock.

“Nowadays, there is a lot more visibility about when blocks are coming than before, so people have more time to prepare,” says Nick Hanbury-Williams, head of block trades at UBS. “Nobody knows how much money has been lost but it is very rare these days to make money on a block trade,” he adds.

The increased risk, against a backdrop of highly volatile market conditions in the past few years, and depressed commissions, are taking their toll on the banks. Merrill Lynch estimated that banks lost ?80m in European bought deals/block trades last year alone.

Among those transactions singled out as loss leaders is Citigroup’s €1.8bn block trade in shares of Infineon Technologies, the German semiconductor manufacturer, completed in January 2004. Some estimates put the bank’s losses as high as €35m after it failed to place the shares above the price at which they were bought.

Morgan Stanley is also estimated to have lost €25m last year on a trade in shares of telecoms provider TeliaSonera on behalf of the Finnish government. And Goldman Sachs is believed to have lost €40m on a trade of shares from Telenor, the Norway-based communications, IT and media firm. Deutsche Bank’s €1.6bn trade for Scania, the Swedish truck manufacturer, lost money and Joseph Manko, Deutsche’s head of equity syndicate, subsequently left the bank.

But as one source pointed out, these figures are only losses if realised on a bank’s balance sheet. Ultimately, it is about managing risk: keeping the stock on the books until market conditions improve and the stock can be dribbled out into the market at price or at a premium. And those banks with large enough balance sheets to fund the holding of stock will be among the winners.

Cross subsidisation

“Margins are very tight in [the bought deals] business,” says Craig Coben, managing director, equity capital markets at Deutsche Bank. “It’s a very risky business and there is the temptation to buy league table glory through a loss-making bid. But you can still make money. The right strategy is to be selective and to pursue those blocks where you have a strong trading or distribution capability.”

Craig Coben, managing director, equity capital markets, Deutsche Bank

And many agree that it is a much tougher regime. In the bull market of the 1990s, banks typically made a profit of 1% on block trades. Now there is no such luxury. “To break even is good,” says one disgruntled ECM banker.

Fees for executing European deals are still coming under increasing pressure. In the late 1990s, banks could enjoy fees of 3%-4% on IPOs that are now nearer to 2%. Convertibles could command fees of 1.75%-2.5% but it is now proving difficult to get more than 1%.

US differences

Meanwhile, fees in the US have largely held up over the years, supported by an informal cartel among the banks. Banks can still earn 5%-7% on IPOs and 3%-5% on follow-ons.

“The windfall profits in the US have helped US banks to subsidise their European business,” says one source who wishes to remain anonymous. “For US banks, the primary motivation is to be top of the ECM league table, globally. It is largely driven by internal political logic.”

Banks that have huge balance sheets are typically called to bought deal auctions and, although they may lose €20m-30m in some trades, they make a profit in one or two. “The US market is a quasi-oligopoly,” says Xavier Larnaudie, head of equity syndicate at Calyon. “Fees have hardly changed there for years. It enables US banks to be very aggressive on bought deals globally thanks to the returns they make in their home market.”

Many agree that US banks’ large balance sheets and sizeable fees made in the US have helped to cushion the institutions against losses in European ECM. However, some suggest that this is causing enormous strain within the US banks and that bankers are unwilling to subsidise other divisions within an institution. Not surprisingly though, US bankers dispute the claim that they are responsible for the direction the business has taken over the last few years and for cross subsidisation of ECM fees between the US and Europe.

“It’s a natural progression for the business. You can do large block trades because of greater liquidity in the market,” says John Millar, head of European equity syndicate at Merrill Lynch. In answer to the claim that US fees support European ECM losses, Mr Millar is dismissive. “Ask any manager if there’s cross subsidisation and he will tell you that he doesn’t get a cheque from the US.”

And the market is not short of banks scrambling to execute such high-risk transactions. Even after Merrill Lynch had been appointed sole bookrunner earlier this year for a £1.42bn accelerated deal in Royal Bank of Scotland stock by selling shareholder Santander, one source comments that three banks contacted RBS to win the business over from the US bank.

Polarisation of players

In line with the reduction in fees has been the shrinking size of syndicates employed to distribute stock. In the past, many continental European privatisations enjoyed a cast of thousands. Regional tranches had their respective lead managers and bookrunners who reported to the global co-ordinator and overall global bookrunner. However, the need for large syndicates to provide distribution capability has long gone.

By the end of the bull market, syndicate sizes were already shrinking, although banks were still undertaking two weeks of pre-marketing for an issue followed by two weeks of roadshows/bookbuilding for marketed deals. Nowadays, there are few roadshows lasting more than a week for secondary offerings, although two weeks of pre-marketing and two weeks of bookbuilding are still undertaken for IPOs.

Along with the accelerated pace of distribution has come the need for smaller syndicates. As one source notes, bookrunners do it all and take all the economics. The ability of junior syndicate members to add value through research has become marginalised.

Consolidation expected

Mr Hanbury-Williams states: “All banks will need to look at the cost base and see whether it’s profitable to stay in the business.” However, regional banks are still viewed as having a unique role in European ECM in generating demand from domestic investors.

However, many believe that, eventually, the ability to undertake major European transactions will be left in the hands of only half a dozen banks as others are squeezed out of the international business and confined to their home markets. And most of those six will be US houses, with names such as Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley high on the list.

“European banks are still putting up a fight on the ECM front. US banks are not there yet in terms of dominance but nearer to being so than five years ago,” says one European banker.

Nevertheless, investor sophistication and greater market liquidity have moved the business forward to a new plain that is perceived in some quarters as being in danger of becoming commoditised.

In January, Goldman Sachs announced the merger of its financing and investment banking departments in a move to increase cross-selling and attract new clients. The bank has integrated its financing group, which comprises equity capital markets, debt capital markets, other related parts of the securities divisions and leveraged finance, into its investment banking business, which includes its M&A and private equity divisions.

This integration of ECM and debt capital markets (DCM) at Goldmans suggests to some ECM players that the writing is on the wall. “The amount of time spent in preparation for these bought deals is very low,” says one source, who believes that ECM is becoming as fast a turnaround process as DCM.

Mr Hanbury-Williams disagrees. “ECM is not likely to become as commoditised as DCM. Issuing stock is a bigger decision than launching a bond issue. Companies care a lot about who handles the sale of their shares. Banks need to have in-depth knowledge of a company’s shares and what investors feel about the stock. If a company’s shares are being sold by a third party, the company will often make a plea to the seller about who sells the shares,” he says.

Good research and a strong brokerage business remain behind the success of nearly all the key ECM players.

Tough competition ahead

Looking ahead, though, most players appear to agree that syndicate sizes will continue to shrink and fees will continue to come under pressure. “European governments will continue to provide us all with a lot of work,” says Mr Hanbury-Williams, referring to privatisations. “These will be sizeable transactions and the fees will be very, very competitive.”

In the past four years, corporates have been restructuring their balance sheets and building up their capital bases through rights issues to get their credit ratings back on track. So companies, particularly from the telecoms sector, are unlikely to be major issuers of stock in the short term. Meanwhile, IPOs will continue to emerge but IPOs undertaken by financial sponsors will be aggressive on the fee front.

And the fast pace of execution looks set to stay. “Most secondaries will be backstop or bought deals,” says Merrill Lynch’s Mr Millar. “Only IPOs will be marketed and even then, done in a matter of days rather than weeks.”