Visible presence: Anheuser-Busch InBev, which owns a non-controlling 50% stake in Grupo Modelo, which brews Corona, was an early entrant to the debt markets this year

After a dismal 2008, the fixed-income sector has bounced back in 2009 thanks to government intervention steadying investors' nerves. The turbulent economic climate has favoured the low-risk bond market but, as revenues and deal volumes have risen, not all of last year's major players have retained their market shares. Writer Joanne Hart

It would be no exaggeration to say the fixed-income markets spent the last quarter of 2008 in a coma. Nothing was happening, there was no sign of life and it was unclear if the patient could ever be resuscitated. The shock to the system was so great it was impossible to guess what kind of damage had been done and what kind of state the market would be in if it ever regained consciousness.

Fast-forward to the summer of 2009 and last year seems like a bad dream. The patient has not only recovered - he seems to be in ruder health than ever.

Talk to anyone in the fixed-income space and they will agree: 2009 has been a bumper year so far. Deal volumes have risen, deal numbers have risen, competition has increased and spreads have come down.

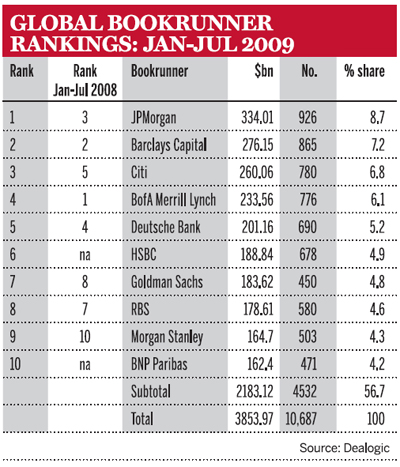

In the first seven months of this year, global debt capital market (DCM) issuance stood at $3850bn, an increase of 21% over the same period in 2008. Within that figure, investment grade volumes were up 45% year on year to $1850bn and even high-yield volumes rose 25% to $119m. As The Banker went to press, global corporate bond issuance topped $1000bn for the year to date, the first time it has broken through this threshold in a single year.

Fee income has also been impressive. Total revenues in the first half of the year were $9.4bn, up 2% compared with the same period last year, but more than double the $4.46bn of revenues made during the second half of 2008. Revenue from investment grade bonds reached a record $4.5bn in the first six months of 2009, a year-on-year increase of 21% and fees from high-yield bonds surged 61% to $1.1bn.

To a casual observer, such a strong and swift recovery in market conditions may seem somewhat strange. But closer examination reveals a number of factors behind the recovery and some key changes between the markets of today and the markets of yesteryear.

Debt markets rebound

Debt markets, at their most basic, are affected by the needs of three subsets - borrowers, investors and arrangers. At the end of last year, each of these subsets was either inactive, incapacitated or both. However, as 2009 began, it became clear that something had to give. Borrowers needed capital, investors needed to invest and arrangers needed to work.

Initially, the market was dominated by sovereigns, supranationals agencies and government-guaranteed debt. The mood was cautious and even these borrowers were paying spreads of 70 to 100 basis points over Libor. Within weeks, however, corporates re-entered the market.

"In the first quarter, there was an explosion of issuance and some very visible, high-profile names came to the market, such as Merck and Anheuser-Busch InBev," says Mark Bamford, head of global fixed-income syndicate at Barclays Capital.

"Throughout that quarter, investors were very risk averse. They focused on high-quality names and they demanded generous returns. As time went on, investors became more comfortable that government financing programmes were working so spreads rallied on high-quality borrowers and lower-quality names began to enter the market," he adds.

The A-B Inbev deal provides a graphic illustration of the way spreads have tightened since the beginning of the year. Launched on January 21, the largest tranche of the transaction, a €750m four-year offer, was priced at 475 basis points over mid-swaps. By August, it was trading at a spread of 140 basis points. Spreads on a second tranche - for €600m over eight years - narrowed from 537.5 to 165 basis points.

Even in recent months, spreads have tightened substantially. Pfizer's acquisition of Wyeth, part financed by a multi-currency bond deal, was launched at the end of May including a €2bn, 12-year tranche priced at 195 basis points over mid-swaps. Just three months later, the spread had come in by 100 basis points.

Mark Bamford, head of global fixed-income syndicate at Barclays Capital

Key factors

Aside from the deal pipeline simply re-opening, this dynamic has also been driven by two key factors: a shift from syndicated debt to capital markets debt on the part of borrowers, and a search for yield on the part of investors.

"There has been a surge in supply this year. Corporates have rushed to secure liquidity after the markets were effectively frozen at the end of last year. And there has been less issuer confidence in the depth of bank market versus capital markets financing," says Huw Richards, head of high-grade Europe, the Middle East and Africa DCM at JPMorgan.

"Corporate bond issuance has been extraordinary, particularly in Europe. European corporates have traditionally relied on the loan markets, but this source of capital effectively disappeared last year. So what we hoped would happen in 1999 with the advent of the euro is finally happening now as corporates are relying more on bond markets," says Eirik Winter, head of DCM for EMEA at Citigroup.

This explosion of supply could not have occurred without corresponding demand from investors.

"Fixed income has been a favoured asset class this year. At the beginning of the year, in particular, equities started on a weak note and investors were able to secure coupons of 6% to 8% on high-quality, household names. Even now, corporate spreads are compensating investors for the risk of historically high default rates," says Mr Richards.

Earlier this year in particular, issuers needed to borrow and investors were very liquid, says Martin Egan, global head of syndicate at BNP Paribas. "Even now, investors remain keen on the debt markets, at least in part because there are few alternative attractive investment opportunities."

A summer deal from EADS illustrates the point. The European aerospace group, rated A1/BBB+, launched a €1bn seven-year bond at 145 basis points over mid-swaps. Orders came in for €9bn of paper.

"This was supposed to be the quiet period but investors remain actively focused on the market," says Mr Richards.

Over the past few months, there has been a slight shift in activity. DCM revenue was up 11% to $5bn from the first quarter to the second, but investment grade issuance began to slow, accounting for 41% of total DCM revenue.

"Risk appetite is returning," says Mr Winter. "Two out of every three bank bonds are issued without a guarantee. Covered bonds are coming back. Spreads on supra-nationals and sovereigns are now close to Libor. We have had 15 to 20 emerging market issues. Even the high-yield market is beginning to return. The final step will be the return of the securitisation market, and I think we will see signs of life there by Christmas," he adds.

Huw Richards, head of high grade EMEA DCM at JPMorgan

Rise in optimism

Other market players are optimistic about the future too. "I don't think that we are going to see a huge return to complex products, but overall bond issuance is likely to be higher than it has been historically. Supply in 2010 will probably be higher than 2006 and 2007, as more issuers use the capital markets to source funds and acquisition activity picks up. This in turn will create additional refinancing activity," says Mr Richards.

"It is possible that this will be the year when we see a step-change in Euromarket supply," he adds.

The driver behind this evolution is the decline of the syndicated loan market - revenues in this sector were at their lowest since 1996 in the second quarter of this year at $920m, a 68% year-on-year decline. "The loan market is not going to reappear for a long time," warns Mr Egan.

"There is a shift from an over-reliance on the bank market into the term bond market. This will happen everywhere and it will take years, proceeding at a different pace in different regions and countries," says Mr Bamford.

"A number of high-quality corporates, who sourced 60% to 70% of their funding from commercial banks for years, are now using non-bank sources for 50% to 60% of their capital needs," says Spencer Lake, head of DCM at HSBC.

As this shift evolves, a number of investment banks will be keen to benefit from the transition, particularly as some players were more focused on their own internal problems late last year and at the beginning of 2009, so they were less able to compete aggressively for market share.

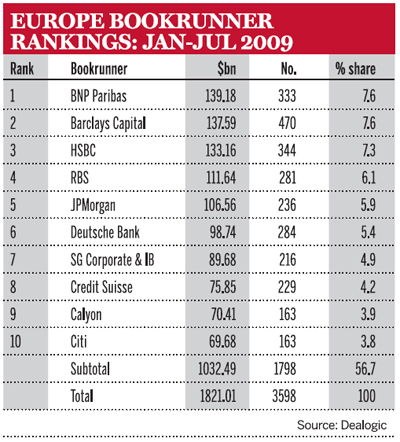

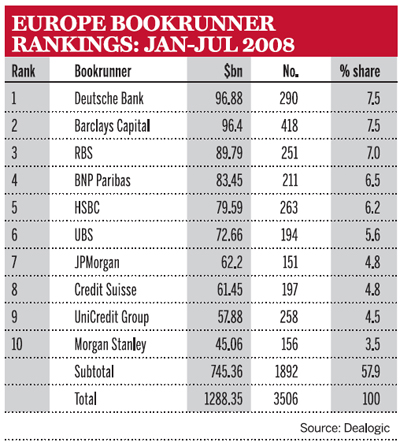

Market shares

BoA Merrill Lynch, for example, was number one DCM global bookrunner in the first half of 2008: this year it ranked fourth with JPMorgan, Barclays Capital and Citigroup ahead of it. In Europe, Deutsche Bank was number one in the first half of last year. This year, BNP Paribas took the top spot. Barclays Capital came second and HSBC moved up from fifth to third.

"Issuers are looking for lead managers that are big and robust: firms that are committed to the markets, firms that are strong and firms that will be there in the future," says BNP Paribas' Mr Egan.

Many players focused heavily on structured products at the height of the bull market, spending less time, money and effort on plain vanilla markets. Some of these are now having to play catch-up, hiring aggressively to beef up desks that had reduced in size and importance over recent years.

"We got to a point at the most bullish stage of the market where it was hard for firms to differentiate themselves, based on execution. But over the past year, the ability to execute well has become more important than anything else," says Mr Bamford.

Many banks have also retrenched in terms of geographic reach.

"Some of the winners of the past are no longer able to compete. The game has changed and clients are looking for firms that can deliver holistic solutions not just isolated products," says Georges Assi, co-head of fixed-income for EMEA at Nomura.

The crisis - and government intervention - has meant people are looking much more closely at who banks are lending to. "US commercial banks are focused on the US and certain European banks are focused on Europe or their own domestic jurisdiction. The world has become more regional," says Mr Bamford.

This suits some borrowers but clearly not all. "The larger issuers are looking for global reach in advice and distribution," says Mr Richards.

The year ahead

The next six to 12 months will be extremely revealing. Risk appetite is clearly returning, but certain products remain out of bounds and certain significant players are still licking their wounds.

"I think two important lessons have been learnt from the crisis. Simplicity is better than complexity and banks need to be in the moving business not the storing business," says Mr Bamford.

"Investors want to understand the risks they are taking on and also want to make sure they are being compensated for them. Banks kept too much on their balance sheets. Now they will move risk on, not warehouse it," concludes Mr Bamford.