Leveraged finance: bubble, bubble, toil and trouble?

Life is a dream for US and European leveraged borrowers, with everything from terms to pricing working aggressively in their favour. Participants claim the pre-crisis excesses are a thing of the past, but there are new risks lurking in today’s record-breaking volumes. Danielle Myles reports.

Throughout 2017 a multitude of markets were labelled frothy. From equities and real-estate to Bitcoin and exchange-traded funds, valuations hit sometimes dangerous highs. Concerns about asset bubbles – being a situation where prices become disconnected to the asset’s actual value – abounded.

Leveraged finance, consisting of leveraged loans and high-yield bonds, was regularly included in this grouping. Indeed, over the year this form of finance – which involves lending to highly indebted borrowers or in such volumes that they become highly indebted – hit crisis-era volumes and featured rising leverage, aggressive terms and record-low pricing.

How did we get here?

There are parallels between these statistics and the heady days of 2006-07, when excessive build-up of leverage across all markets became a root cause of the financial crisis. Issuance of leveraged loans with borrower-friendly terms surged during those years, and when the market crashed in 2008 banks were left holding risky debt they could only offload at fire-sale prices, while investors were burnt in restructures of leveraged buyouts (LBOs) that proved uncreditworthy.

The main driver of the current boom is ultra-low interest rates. Borrowers are taking advantage of cheap debt, and for investors on the hunt for yield the non-investment grade returns are better than what is offered elsewhere. Money has poured into the asset class with collateralised loan obligations (CLOs), among the biggest buyers of leveraged loans, raising more funds in 2017 than any post-crisis year.

Bankers are just the intermediaries in this market. They underwrite and then syndicate the debt, agreeing – subject to US and European Central Bank (ECB) guidelines – to terms they believe the market will bear. Some of them, along with analysts and investors, are concerned that financial sponsors (primary users of the loan product) have too much power, that prices and terms do not adequately protect investors, and that there is too much risk in the system. In January 2018, the Institute of International Finance described the surge in loans with borrower-friendly terms as ‘a potential risk to financial stability’ which should be closely monitored.

The reality is more nuanced than the headline statistics suggest, and the consensus is that leveraged finance isn’t repeating the last ill-fated cycle. But there are some warning signs – namely volumes, leverage, covenants and pricing – which suggest the market is not without its dangers.

Warning 1: Volumes

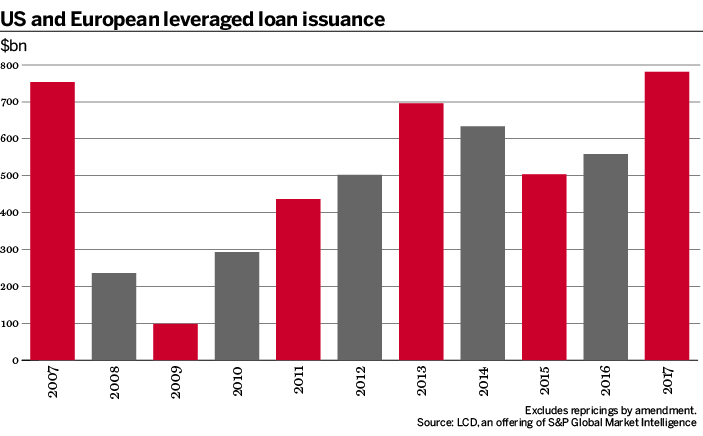

Banks arranged $782bn of leveraged loans in 2017, the highest annual volume since the financial crisis according to LCD, a division of S&P Global Market Intelligence. European volumes more than doubled those of 2016, while US issuance hit an all-time high of $646bn. Europe also posted a record $106bn in high-yield issuance. Notably these figures exclude the wave of so-called re-pricings, perhaps the ultimate show of borrower power whereby they amend loans solely to lower the interest rate.

Yet record-breaking activity has not redressed the supply-demand imbalance, because more than half of these deals were opportunistic refinancings or dividend recapitalisations whereby sponsors take out additional debt secured by a portfolio company to pay their limited partners a dividend. Some 70% of 2017’s high-yield issuance was for one of these two purposes. While mergers and acquisitions spiked in the second half of the year, with sponsors announcing LBOs of the likes of drugmaker Stada and payment firms Nets and Paysafe, overall there have been limited opportunities to put money to work. It means competition among investors is tougher than ever, which has further empowered borrowers.

Warning 2: Leverage

Leverage levels, measured as the borrower’s total debt compared with its earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda) have crept up on both sides of the Atlantic. LCD stats show that in 2017, Europe’s total leverage was 5.1 times Ebitda, less than the 6x posted in 2007 but still a post-crisis high.

In the US, leverage in LBOs, the market’s riskiest segment, has reclimbed to 5.8 times Ebitda (after dropping from 6.2 times in 2007) but bankers are not concerned. “There has been a gradual uptick in leverage but the regulatory framework on the larger deals has acted as a bit of a governor, so there is often more equity in transactions,” says Christina Minnis, Goldman Sachs’ global head of acquisition finance and co-head of its Americas credit finance group. Indeed, US banks have faced regulatory scrutiny for underwriting deals that exceed the 6 times Ebitda cap in national leverage lending guidelines.

Bankers also highlight that leverage multiples are a blunt tool, and that repayment ability requires consideration of other factors too. “Last time around there was a lot of focus on headline leverage, whereas today investors are focused on free cash flow,” says Chris Munro, Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s head of leveraged finance for Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA). “It’s a more accurate reflection of a company’s ability to service its debt than just an Ebitda number, and free cash flow multiples are much more robust today than in 2006-07.”

Bankers see a growing number of 6 times or 7 times Ebitda deals (Fitch says the Nets and Paysafe LBOs exceed the 6 times threshold set by the ECB) but they also highlight the sharp dichotomy between these credits and those that attract lower multiples. “Where you see very high leverage levels for companies with existing syndicates that are known to the market, they are generally returning issuers or borrowers, or they have a revenue and cash-flow profile that is reasonably defensive,” says Mathew Cestar, Credit Suisse’s co-head of EMEA capital markets and investment banking.

Nonetheless, there are widely held concerns about whether these multiples are a true reflection of leverage. This is because add-backs, being adjustments that inflate Ebitda figures, have become more aggressive. Europe’s leverage guidelines are flexible on this point, meaning the practice will not stop anytime soon.

Another concern is that first-lien debt, which consists of leveraged loans, is more highly levered than in 2007 and accounts for a large portion of borrowers’ total debt. This erodes the benefit of their high ranking in the capital stack. “The bigger and more levered that part of the capital structure becomes, the less there is for recovery post-default,” says Taron Wade, director at S&P Global Market Intelligence. “It’s a worry as these lenders would usual rely on a cushion of lower ranking debt if a company defaults.”

Warning 3: Covenants

In loan and high-yield documentation, the steady erosion of covenants, which limit the borrower’s ability to engage in activities that could jeopardise its repayment ability, have left investors with fewer contractual protections than in the past. The best example is the rise of covenant-lite (cov-lite) loans, which do away with so-called ‘maintenance covenants’ that allow senior lenders to regularly inspect the borrower’s leverage, cash flow and expenditures.

Cov-lite has been market standard for US large- and even mid-cap deals for some time. Its arrival in Europe in 2014 was met with scepticism, but today it is the market standard for large-cap deals. According to LCD, in 2017 three-quarters of European and US leveraged loans were cov-lite. For large-caps, certainly LBOs, maintenance covenants have almost become stigmatised; if the loan includes one, it suggests a weakness in the borrower.

Recent MSCI research found that during "adverse financial conditions" cov-lite has a higher probability of default than covenanted loans. Yet proponents highlight its creation of a more balanced market which is no longer dominated by bank investors and is better suited to institutional investors. “The institutionalisation of the market has hugely benefited the asset class through the amount of liquidity available and the diversity of issuers. It also allows banks to be more focused on structuring and distribution rather than holding exposure,” says Patrice Maffre, Nomura’s global head of acquisition and leveraged finance.

Nonetheless, he is part of the chorus of market participants asserting that cov-lite is not appropriate for small borrowers, which often carry more business risk than bigger borrowers. “Smaller companies typically have less product and geographical diversity, may have more key person risk and are more likely to operate in fragmented sectors,” says Edward Eyerman, Fitch’s head of European leveraged finance. “Plus their market positioning and pricing power is less demonstrated than some of the larger incumbents.”

Despite this consensus, LCD data shows that in the third quarter of 2017, more than 40% of loans worth $350m or less were cov-lite. Its creep into the lower end of the market has coincided with the adoption of a milder form known as ‘cov-loose’, which includes one or two maintenance covenants, by the plethora of direct lenders that specialise in smaller leveraged credits.

Cov-lite aside, loans have become more borrower friendly in other ways, including more stringent restrictions on investors’ ability to transfer the debt. “That was always the quid pro quo for cov-lite; we won’t offer you maintenance covenants, but this is a large liquid deal that you should be able to sell if something goes wrong,” says Ms Wade.

In high-yield, the erosion of investor rights, such as call protection and caps on debt incurrence, has been exacerbated by the rise of passive money which is less likely to push back on aggressive terms. These funds are attracted to the asset’s relatively high returns, but when a borrower hits trouble these returns disappear unless they are accompanied by covenants that rein in management and bring creditors to the table. “You can have a 9% coupon, but that’s attractive only up to the point that the company can only sustain a 4% rate,” says Mark Wade, head of industrials and utilities research at AllianzGI.

Warning 4: Pricing

Another concern is that yields on high-yield bonds are nearing historical lows, particularly in Europe, where interest rates are still zero and quantitative easing continues. In mid-January, Credit Suisse’s European high-yield index, which tracks the yield-to-worst of outstanding issuance, was just over 3.5%. “There’s a lot of focus on leverage, but in my view the risks are around how low some of the coupons have got,” says Mr Cestar at Credit Suisse. Syndicate bankers at other lenders share the same concerns, and investors note that spreads on BB credits do not compensate them for the default risk or give them an illiquidity premium as they did in the past.

The cost of capital in Europe’s loan market also hovers around historical lows, but bankers believe LBO pricing is nearing a floor, and stress that coupons are set differently to pre-crisis years. “Today there is much more price elasticity and documentation tools to reward the best performing credits,” says Mr Maffre at Nomura. “People often forget that prior to 2007 the market was more static with the main mode of adjustment being leverage.”

What could go wrong?

With the leveraged finance cycle now in its late stages, these warning signs beg the question: what happens once the market eventually turns? It is a long way from a 2008-style collapse. There is now a broad mix of lower levered investors with different strategies, meaning the risks are widely dispersed. As Ms Minnis notes, today’s CLOs are backed by a lot more equity and longer term capital than the crisis-era vehicles, and the amount of underwriters’ unsold loans and bonds is about $21bn compared with nearly $300bn in 2007. “Ten years ago, there was a huge amount of supply sitting on banks’ balance sheets ready to come to market when the downturn hit. That was a big technical problem that we don’t have today,” she adds.

In Europe, the end of the ECB’s corporate bond-buying programme is tipped to be a turning point, but the fallout is not expected to reach issuers’ underlying businesses. “At that point, some of the money will go away but my guess is that will lead, at least to start off with, to a sell-off in asset prices rather than a massive increase in the default cycle. That’s because many of these companies have done a great job using cheap money to term-out their debt,” says David Newman, AllianzGI’s head of global high yield.

There are pockets of weakness, such as UK and US retail, as illustrated by Toys R Us recently filing for bankruptcy protection after reportedly struggling to service its debt following its 2005 LBO. But default rates are forecast to remain below 2% in 2018, as supported by the fact credit is still widely available via bank and bond markets. “When lending standards start to tighten in the US and Europe, that is the most likely precursor to a broader rise in default rates,” says Mr Wade, citing the recent commodity crisis as an example. However, when defaults do occur, Mr Eyerman says higher senior leverage and less junior debt mean recoveries for leveraged loan investors will be materially lower.

Leveraged finance 2.0

According to bankers, the main reason leveraged finance is neither in a bubble nor at risk of widespread defaults is because they and sponsors are much more rigorous in assessing borrowers and targets, respectively, than they were a decade ago. Their focus on credit quality, cash flows, customer base, track record and an ability to perform in a low-growth environment sets a high benchmark for those wanting to tap the market. Indeed, the capital-intensive and fading industries at the centre of pre-crisis LBOs that have since been restructured (telephone directories businesses, for example) are nowhere to be seen.

However, not all market participants are convinced. A few high-yield deals were pulled in 2017, some due to investor concern about the business. Meanwhile French telecommunications company Altice, Europe’s biggest issuer of leveraged debt, has seen its share price tumble since mid-2017 following profit and revenue warnings.

With the proliferation of direct lenders and more banks acting as underwriters (Mr Munro of Bank of America Merrill Lynch is surprised by the types and number of banks he sees around new situations), the market is more competitive than ever. It is vital that this doesn’t lead to a slip in discipline on borrower quality, not just to avoid a bubble, but also because these are the deals being rewarded by investors. As Mr Newman notes: “You can live with leverage in a good business or even weaker covenants in a business where you trust the management team. But where the business itself is just bad, they are the ones where you see pushback at the moment.”