Leading investment banks’ lucrative relationships with hedge funds have multiplied across a number of business silos. But their exposure to risk has grown too. Could their overlapping business lines spell trouble in difficult markets?

For some time, hedge funds have been marked out as a potential source of risk in financial markets. What has been missed is the extent to which hedge fund-related risks may now be nestling inside the leading bulge bracket banks. Banks have increased their exposure to hedge funds through prime brokerage, which often involves providing credit to funds; sales and trading on behalf of hedge funds; increased proprietary trading that often involves hedge funds as counterparties; investments directly in hedge funds; and further investments through their asset management arms. The banks have been driven into these businesses by the search for yield at a time of falling investment banking revenues. But there is concern that a sudden spike in interest rates or other unforeseen event could expose risk positions in banks that are much more onerous than current models suggest.

“[The mentality seeping across the industry] is reminiscent of the hedge fund trading and Russian bond trading that occurred prior to the summer of 1998,” says David Hendler, senior analyst, financial services, at independent US research house CreditSights. “At that time, it seemed that any credit risk trade could get down as long as the fixed income and commercial banking community was lathered up to accommodate.

“However, when a market event occurred, the liquidity that participants had taken for granted disappeared as credit, market and counterparty credit concerns escalated and substantially shut down the markets. Higher interest rates can be a contributing factor in reducing trading volume and, combined with a wild card unforeseen event, lead to huge disappointments in earnings and possible sizeable capital hits. Recent upward spikes in interest rates, whether Q3 2003 or Q2 2004, were a preview to the liquidity trap that caught some mortgage hedgers. And third-quarter trading losses on wrong way bets show how proprietary trading can influence earnings on the downside,” Mr Hendler says.

Investment banking slide

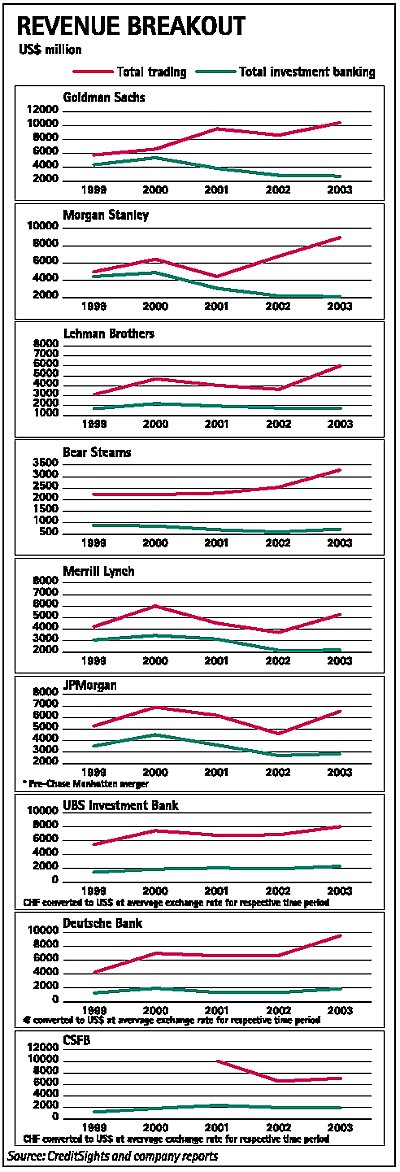

How did the banks get into this situation? It began with a drop off in investment banking earnings. Between 1999 and 2003, Goldman Sachs’ financial advisory figures halved from $2.27bn to $1.2bn and Morgan Stanley’s M&A advisory shrank from $1.89bn to $662m. Merrill Lynch’s equity capital markets revenues dwindled from $1.25bn to $762m, Goldman’s debt capital markets revenue dropped from $2.08bn to $831m and Morgan Stanley’s fell from $1.28bn to $795m in the same timeframe.

This dispiriting revenue trend shows that, since the end of the bull market, M&A and IPO markets have failed to deliver the returns that these expensive franchises demand, and large corporations on both sides of the Atlantic have focused on balance sheet adjustment so that demand for new funding, whether via bond issuance or bank lending, has been low.

But equity markets expect large financial institutions to produce consistently high returns, punishing their share price if they do not. And CEOs take heed of investor sentiment. Joseph Ackermann, for example, has pledged that Deutsche Bank will lift pre-tax return on equity to 25% by next year. In Q3, it was 16%. When one division underperforms, another must take up the slack. Now, investment banks are looking to sales and trading to support the bottom line. But this business arm has done more than that: it has helped some firms, such as Goldman, to announce record quarterly revenues earlier this year.

In particular, the fixed income franchise, including derivatives, currency and commodities, has continued to perform. Goldman’s fixed income, currencies and commodities (FICC) division’s revenues rose from $2.86bn in 1999 to $5.59bn in 2003. Morgan Stanley’s fixed income sales and trading grew from $1.9bn to $5.35bn. Lehman Brothers’ rose from $1.66bn to $4.39bn, Merrill’s from $1.82bn to $4.42bn and Deutsche Bank’s from $3.02bn to $6.75bn.

Equity trading revenues have risen slightly or remained flattish. At Goldman Sachs, overall sales and trading revenues – including equities trading and principal investments – have almost doubled in four years, from $5.77bn to $10.44bn. Similarly, Morgan Stanley’s total trading revenues shot from $4.96bn to $8.94bn. The story is the same at Lehman ($3.90bn to $6.01bn). In the first three quarters of this year, sales and trading contributed 65% of Deutsche Bank’s corporate and investment bank revenues, while advisory and underwriting represented only 13%.

Not only have revenue streams tilted towards sales and trading. There has also been the rise of FICC in management hierarchies. At Deutsche, Anshu Jain was recently appointed co-head of the corporate and investment bank, and added responsibility for all sales and trading, including global equities, to his role as head of the global markets division. And Lloyd Blankfein, previously head of FICC at Goldman, was appointed president and chief operating officer of the firm this year. Most assume that he is chief executive-in-waiting to Hank Paulson.

Risk and reward

To generate such trading revenues, banks had to ramp up their risk profiles. A report from Boston Consulting Group (BCG) released in September illustrates that in the second quarter of this year, “risk efficiency” (based on revenues and risk taken) had declined from 23.2 to 17.9. “Banks [are finding] it increasingly difficult to improve revenues at a given level of risk,” says Svilen Ivanov, a partner at BCG.

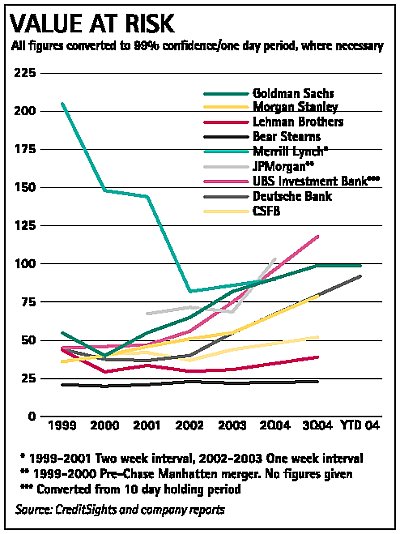

Value at Risk (VaR) – which measures the potential loss in the value of trading positions due to adverse market movements over a defined period with a specific ‘confidence’ level – has risen, almost across the board. It is a calculation based on volatility and trading positions and, although it does not offer a complete picture of a firm’s risk, its increase signals aggressive trading, not least because in a low volatility environment, trading positions must have increased significantly to push up VaR figures.

Comparing VaR levels is difficult. Firms use different underlying data, as well as different defined periods and confidence levels. Nonetheless, comparing firms’ own VaR figures, the rise has been dramatic at many banks. Goldman’s 2003 10-K (the year-end filing to the US Securities and Exchange Commission) revealed that its average daily VaR (converted by CreditSights from a 95% to a 99% confidence level and a 1-day basis), taking into account the ‘diversification’ effect of what investment banks see as ‘non-correlated’ risk, had jumped by 26% from 2002 levels and has almost doubled in the past few years. In Q1 2004, Goldman’s average daily VaR rose to an industry high of $100m – up 20% overall and 25% in FICC on a linked quarter basis, says CreditSights. At Morgan Stanley, aggregate daily VaR rose by 31% in 2003 and, according to BCG, Deutsche Bank hiked its VaR by 26% and JPMorgan’s rose by 33% in Q2.

Proprietary risk

Underpinning the growing importance of sales and trading, are higher levels of proprietary trading – trading on behalf of the firm rather than for a client. Distinguishing proprietary trading from client-driven trading is not straightforward, not least because banks do not openly break out the figures. A prop position may result from taking a client trade or the bank may base a proprietary trading strategy on the flows that it sees on its client-servicing desk. However, increasing VaR is an indicative, if blunt, measure of firms’ burgeoning appetite for proprietary risk.

Deutsche Bank has admitted that about 30% of its trades are proprietary – which led many to believe that the figure is probably higher and The Economist magazine to suggest that Deutsche is a hedge fund with investment banking capabilities. In what analysts interpreted as an acknowledgement of its proprietary tendencies, Goldman’s letter to shareholders with its 2003 annual report was unapologetic about the level of risk taken, arguing that this was one of the firm’s distinguishing features. “[It] is our willingness to tolerate such occasional, sizeable losses that enables us to earn attractive returns over time. And, even when our trading businesses are performing well, results can be uneven,” wrote Mr Paulson.

Profit and loss

Prop trading has helped the banks to post some excellent returns. In 2003, Goldman’s FICC revenue was up 20% on 2002. In Q1 this year, results soared past analysts’ expectations. Reported earnings were up $1.3bn, with trading and principal investing (including FICC) commanding 69% of overall revenues, and investment banking just 13%. FICC stole the show, up 85% and $967m on a linked quarter basis.

Losses can be big, too. In its Q2 conference call with analysts, Goldman noted that a broad range of relative value trades in equities went against it, dragging equity trading down about $595m, 63%, on a linked quarterly basis. In Q3, Morgan Stanley’s earnings were down $386m (32%) on a linked quarter basis and ‘principal transactions trading’ dropped by 66%, driven by a reduction in trading revenues of $1.4bn. The company says that the decline was indicative of its swaps position and a change in its accounting procedures. But in the analysts’ call at the time, the firm also admitted that it had been on the “wrong side” of an interest rate view. JPMorgan also admitted to being on the wrong side of several interest rate positions in Q3 (trading revenues were down by about 40% on a linked quarter basis), although it said it was not a purely proprietary trading bet but a poor portfolio management position.

A year ago, Citigroup CEO Chuck Prince said that Citi needed to raise its profile in proprietary trading and in Q3, it too got caught out in the interest rate/yield dislocation. It has been suggested that the poor trading results may have resulted in the aggressive government bond trading strategy in Europe (where Citi sold more than E10bn in eurozone paper across about 200 debt instruments, pushing the price down, and buying about E4bn back soon after, capturing a significant profit) in an effort to disguise how volatile proprietary trading results can be.

Deutsche Bank also suffered in Q3. Revenues from its equity sales and trading group dropped for the second consecutive quarter, to E400m (compared with E745m the year before). The bank said “difficult market conditions” adversely affected DB Advisors, its in-house proprietary trading business. It also said, low volatility and narrowing spreads impacted negatively on the convertibles proprietary trading portfolios.

Hedge fund impact

Many believe that the growth of the hedge fund community is driving the increase in trading revenues. The fact that Goldman’s over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives exposure to unrated counterparties increased by 184% between 2002 and 2003 could indicate that it is hedge funds that are the main trading counterparties. While information about this opaque community remains limited, the number of funds is estimated to be about 8000, managing more than $1000bn. According to figures from the TASS Research hedge fund database – which represents a fraction (2802 live funds) of the total number of funds – almost $40bn of new capital flowed into hedge funds during Q4 2003 and Q1 2004.

Their funds under management may be a tiny proportion of the world’s investable assets (about 2%), but hedge funds are more active traders than traditional asset managers, and their high portfolio turnover and more leveraged strategies have a disproportionate effect on investment bank revenues. Because of this, investment banks devote an increasing proportion of their resources to servicing hedge fund needs. Credit Suisse First Boston (CSFB) estimates that hedge funds account for 35%-40% of commissions in equity trading; some analysts put it closer to 50%. Some analysts believe hedge funds also account for 7% of investment banks’ global fixed income revenues; others believe that it is much higher.

Prime brokerage

In another business silo, hedge funds are the engine stoking prime brokerage – a major growth area for some investment banks. BCG estimates that as clients of the prime brokers – which provide clearing and settlement, and margin and securities lending services, among others – hedge funds represented 13% of investment banks’ global equities revenues in 2003. In aggregate, CSFB reckons that hedge funds account for 13% of investment banking revenues.

It is the nature of the financial system that as one business segment flags, the search for yield will lead to another area of growth. It is therefore no coincidence that the biggest trading houses are also the leading prime brokers and, incidentally, the largest derivatives players: it is these business segments that are yielding the best profits. It is also worth noting that as staff have left banks to start hedge funds, banks have often opted to invest in these funds, as well as others.

The risk is in the overlap

While risk is not an “additive” phenomenon, is the overlap between traders, hedge funds and prime brokerage leading to a cumulative risk that is not accurately represented by individual figures? And are banks able to model and manage that risk adequately? One banker calls prime brokerage the “contagion point” of the financial system because it links the unbridled and largely unregulated activities of hedge funds to the wider banking system.

So what is the overlap? Revenue and VaR figures suggest that the biggest proprietary trading houses are Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Deutsche Bank. Other investment banks are not far behind. The two biggest prime brokers are Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, estimated to command more than 46% of the global prime brokerage business between them. The revenues generated by prime brokerage – and the hope that the relationships will also yield increased trading revenues in the investment bank – have led other players to chip away aggressively at this startling market share. In Europe, Deutsche is now estimated to have about 12% of the market. According to one analyst in this area, the top prime brokers also include Bear Stearns, Bank of America, Lehman Brothers, JPMorgan, Citigroup and UBS.

In the derivatives business, much the same players dominate. According to Fitch Ratings, the top 10 credit derivatives counterparties are, in order: JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, CSFB, UBS, Lehman Brothers, Citigroup and Bear Stearns.

No-one is suggesting that we are on the verge of fall-out like that caused by Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) – at the time of its collapse in 1998, it had equity capital of $2.3bn but on-balance sheet assets of more than $125bn (a leverage ratio of 50:1) and gross notional derivatives contracts outstanding to the tune of $1400bn. That experience taught important lessons about counterparty risk management, collateral management, liquidity measures and valuation practices. But old risks remain and some new ones have formed. The financial product and trading strategy universe has become more complicated, the number of hedge funds has at least doubled and trading income has become the lifeblood of investment banking revenues.

Where’s the leverage?

With LTCM in mind, the first question is one of leverage. Studies argue that the degree of leverage in the system or at individual firms cannot be compared to that at LTCM. Hedge fund adviser The Hennessee Group, for example, says in this year’s annual survey that in 2003, hedge funds had an average leverage ratio of 1.41:1, claiming this dispels the notion that hedge funds are a highly levered asset class.

However, Hennessee’s data is limited: the research includes information from only 789 of the estimated 8000 funds. Equally, while individual firms may not be heavily leveraged, the explosive growth in the number of funds means that, in absolute terms, the industry could still represent a significant overall degree of leverage in the financial system.

In the June issue of its bi-annual Financial Stability Review, the Bank of England (BofE) notes that leverage appears to be moderate compared with 1997-1998, although it says this may not be a sensible benchmark. It also states that there are no observable measures of leverage and, in the case of hedge funds, this is compounded by the many different forms that leverage can take, including: margin lending; funds of hedge funds, a rapidly growing sector, which, the BofE says, increase leverage, typically by borrowing from investment banks against collateral in the form of their claims on the underlying hedge funds; and economic leverage, via derivatives or assets that themselves embody leverage.

Hedge funds are certainly driving growth in many derivatives products. Fitch Ratings’ annual global credit derivatives (CD) survey, released in September, reveals that the CD market expanded by 71% in the past year, to $2800bn of gross sold outstanding contracts, including cash collateralised debt obligations. The report states that hedge funds now comprise 20%-30% of trading volume for a number of the more active market intermediaries. Interestingly, 53% of banks cite trading as the dominant motivation for using credit derivatives, compared with 19% that cite credit risk management as their key driver.

Multiple relationships

Multiple prime broker relationships may pose another risk. For hedge funds managing more than $100m, it is common to have two or three, some say more, prime brokers. This expands access to securities hedge funds want to borrow and increases access to financing. While each broker may apply credit controls and collateral agreements – both of which banks say have improved since LTCM – a broker cannot risk-manage a fund’s relationship and trading positions with another firm.

Given the vital role that prime brokers play in monitoring funds and setting terms on leverage, the BofE report and the UK’s Financial Services Authority (in a presentation in October) both acknowledge the limitations that multiple prime broker relationships place on overseeing a hedge fund’s risk profiles and setting appropriate collateral margins, particularly for concentrated and/or illiquid positions.

Additionally, some interviewees suggest that, because there is strong competition for lucrative prime brokerage mandates, some newer entrants are applying what one calls “a looser monetary policy”, and that risk and other controls may not be as strict.

CreditSights’ Mr Hendler agrees: “The broader risk is not just about the prime brokers that are careful risk managers. It is about the environment being ‘polluted’ by brokers that are less careful and feel they need to be more aggressive to win business – whether that is in lending policies or in taking collateral. All the brokers feel they can protect their capital at the precise moment that they need to but that may not be the case if a problem is caused that is beyond their control and that they haven’t identified in time.”

Double trouble

Since they also aim to build trading relationships in their investment bank, the biggest prime brokers must also boast the highest degree of hedge fund-related trading. What dangers lie in having clients on both sides of the Chinese wall separating the trading desk from the prime brokerage? Are there dangers if a prop desk’s trade hits a hedge fund client?

And what if trading desk and client are both trading in the same strategies and products? The BofE report points out the possibility of “crowded trades”, particularly in fixed income and macro investment strategies. It says: “Funds, and bank/proprietary trading desks, use similar ideas or models to identify what may be, at any particular time, a relatively narrow range of ‘relative value’ trading opportunities.”

The report also suggests that there is now greater risk involved in many funds tending to take similar positions (“herding”) rather than in a single, large fund failure. In Europe particularly, many start-up funds are believed to be concentrated in fixed income, currency and commodity markets.

And, the report says, compared with a year ago, funds appear to me more involved in credit markets including leveraged loans, distressed debt and credit arbitrage. “For credit-oriented funds, such as distressed, a combination of leverage, relatively illiquid product and a model-based approach to valuation and trading may, in the event of material asset-based shifts, exacerbate stressed conditions,” it states.

In an e-mailed response to The Banker, Craig Broderick, managing director and head of the global credit risk management and advisory department at Goldman Sachs, admitted that the risk of crowded trades is an ongoing concern. “There remains relatively little transparency across the market as a whole in regards to large individual positions (relative to market liquidity), or multiple correlated positions which can aggregate to large overall positions. However, we are vigilant in our monitoring of hedge fund credit risk against accumulations of risk concentration, and adjust our credit parameters as necessary to reduce this risk,” he says.

Distressed markets

It is in a distressed market situation that the overlaps in products and business lines could become crucial – traders on both sides of a Chinese wall could be unwinding the same positions at the same time. Multiple brokerage relationships could make it difficult to identify impending problems at an early stage.

Equally, there is a high degree of concentration in the key players involved in several product areas – notably prime brokerage, trading, structured credit and OTC derivatives. In severe market stress, what happens to liquidity when many of the same firms are central to the orderly operation of several markets?

Roger Merritt, managing director, credit policy group, at Fitch Ratings, says that after Fitch produced its credit derivatives report in 2003, highlighting the market’s reliance on a relatively small number of key intermediaries (where the top 10 institutions represented 70% of counterparty exposures; and 69% this year), US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan noted that concentration risk was a systemic risk factor. If this is the case in credit derivatives, then concentration risk must also apply to other product lines.

Liquidity is critical. Goldman, for example, identifies liquidity risk as its major concern and says that it maintains a large cushion of cash and highly liquid securities that averaged $38bn in 2003 (up from $17.99bn in 1999). However sensible this is, liquidity management also has its limitations. First, it is complicated by so-called “lock-ins”. Larger hedge funds now often obtain agreements that prime brokers must give, say, 30 or 60 days’ notice before changing margining policies. The BofE has noted this risk. Its report says: “There is a trade-off to be struck between the funds’ desire for stable and so predictable margining at times of market stress, and the ability of brokers to cut their exposure in such conditions.”

Lock-ins and withdrawals

The length of lock-ins between hedge fund and investor could also exacerbate market stress. New, unproven hedge funds often work on minimum lock-ins with their investors, making it easier for investors to withdraw their money if the fund is not performing as expected. The wall of new money that has flowed into hedge funds in the past six months or so has, by definition, gone into new funds. It has also helped to flatten arbitrage and other trading opportunities – lack of volatility has been largely blamed for hedge funds’ disappointing returns since the first quarter of this year. If investor expectations are not met, there could be sizeable withdrawals and, whether that leads to hedge funds trying to liquidate positions quickly would, in turn, depend on lock-in periods and degrees of leverage.

Investment banks deny there is increased risk implied by increased trading and derivatives activity and growing relationships with hedge funds. Off the record, bankers stress that stringent credit and trading limits are adhered to, and all exposures are hedged. However, all the banks approached for this feature declined to be interviewed, aside from Goldman Sachs, which offered a limited response by e-mail.

But in the Fitch survey, all the major players stress that their exposures to hedge funds are collateralised, if not always by 100%. (Fitch notes, however, that it is impossible to estimate the notional positions and “at risk” positions held in the hedge fund community).

From the perspective of liquidity, however, collateral is only as good as its valuation is accurate. And assessing fair or market values is not an exact science at the best of times – the Fitch survey also highlights that a number of firms are “unable to provide attendant market values for bought and sold credit derivatives positions”.

In a world of interlinked and overlapping products and participants, where a view of exposures can be fragmented between a variety of players, what would happen if an abrupt asset price correction spilled over into the broader financial system? What would happen if there were substantial adjustments to portfolios as and when interest rates rise? And how smooth would those adjustments be? What will happen to the value of collateral if there is the equivalent of a bank run in the securities markets? Regulators and banks’ risk managers should be seriously considering the answers to these questions now – and no doubt many are – rather than waiting until the market performs its own kind of stress test.

Risk models under scrutiny At the centre of these issues sit market participants’ risk management processes and technologies. The integrity of firms and the financial markets also rely on the accuracy and reliability of the risk models on which both traders and investors base their strategies. The models are sometimes called into question. The bond markets, for example, have this year disproved what many believed was a rock solid relationship between interest rates and yields. In another example, firms often use dynamic hedging techniques. In complex credit derivatives structures, investment banks often keep a tranche on the balance sheet and ‘delta hedge’ their positions by anticipating the value of the tranche they retain. Aside from the basis risk this may generate – because the hedge and the position are rarely perfectly aligned – how proven are these techniques? Fitch’s managing director, credit policy group, Roger Merritt, says: “Dynamic hedging models have not been around very long and the assumptions underlying the hedges – such as those about the correlations between credits regarding spread movements and default risk – have not been tested in periods of severe market stress.”

Calculating VaR is also far from scientific and does not provide a comprehensive measure of risk; VaR offers no information on the nature of potential losses beyond the reported confidence threshold. VaR also makes assumptions that recent correlations between asset prices will persist; this may not always be the case. What would happen if markets were to become illiquid or disorderly? Some studies have suggested that VaR does not work particularly well with hedge fund risks because the assumptions about correlation in markets do not hold up.

To address these short-comings, banks meld “what if” scenarios to their risk management techniques. CreditSights supplements its assessment of investment banks’ VaR figures to generate what it believes is a more representative figure for severe market situations. Under this framework, the risk picture looks very different. CreditSights’ David Hendler says: “Converting Goldman’s figures to a 99%/1-day basis and applying a six sigma formula to calculate the potential VaR from a fat tail event [such as an exogenous shock to the market], we calculated that, in Q3, Goldman’s average daily VaR increased from $70m to a hefty $255, or roughly 6% of the consensus 2004 estimate earnings per share of $8.36.”

Craig Broderick, managing director and head of the global credit risk management and advisory department at Goldman Sachs, says the bank’s risk management has been substantially upgraded since 1998, but agrees that VaR models have certain inherent weaknesses, including the potential to inaccurately reflect market stress during periods of unusual market stress. “Accordingly, we supplement our VaR analysis with stress scenarios in order to probe client portfolios for risk during these periods, using both historical scenarios and constructed multi-factor scenarios. We also examine client portfolios for concentrations in idiosyncratic risk.” He says the bank also uses complementary contractual terms and optional termination provisions.

A further caveat is firms’ ability to measure risk across multiple business and geographical silos. A recent Fitch survey says: “It was somewhat surprising that many of the respondents to the survey still appeared to have a fair amount of difficulty in aggregating the firm’s exposures or investments in various types of instruments across the company’s different businesses.”

While this instance related to credit derivatives, it may signal the limited capacity of other management information systems. If so, it would prevent risk committees from building accurate pictures of client exposures or the investment bank’s combined exposure on a timely basis.

According to Mr Merritt, this difficulty was partly a function of the fact that some firms manage their cash and derivatives positions together, which made it difficult to extract the information in the format that Fitch required. That said, he acknowledges that the firms that had difficulty in isolating exposures across products and geographies include some of the largest and most active players in these markets. “It is a clear example that management information systems have failed to keep pace with the growth in this market,” he says.

Similarly, the management of risk on a real-time, or near real-time, basis becomes more important when clients and trading desks are working across multiple products, jurisdictions and time zones. Analysts say that such capability is not widespread. For most firms, it remains a Nirvana. According to Denise Valentine, analyst at US research house Celent, while they continue to improve, systems are still segmented across business silos and “risk management is generally done on an end-of-day basis at best”.

Mr Broderick says: “Investment in technology platforms is extremely important in serving our hedge fund clients while simultaneously managing counterparty credit risk. Sufficiently sophisticated models, supplemented with stress scenarios and concentration testing, must be available on a daily basis in order to provide competitive terms to our clients while protecting against excessive credit risk. These risk exposures must then be aggregated by counterparty, by corporate family and by a variety of other attributes. We monitor these risks and act on inappropriately large concentrations. Our systems must also be able to routinely deliver high quality data aggregated at sufficiently high levels for management and regulatory reporting.”