With investors in a state of near permanent paranoia, pricing an initial public offering to perfection is critical in today's market. The list of failed or delayed IPOs in the first half of 2010 is testament to this. Only the strongest will survive - even those at a healthy discount. Writer Charlie Corbett

Dealmakers in today's equity capital markets (ECMs) are in an unenviable position. Starved of issuance in 2010 to date, when a deal does finally go to market it generally prices at the extreme lower end of expectations. In fact, just getting a deal to price at all in such a volatile market can be considered an achievement in itself. ECM bankers are facing an investor base riddled with a deep scepticism and wracked by nerves. As one dispirited ECM specialist told The Banker: "Who on earth would consider an initial public offering [IPO] in a market like this?" The figures bear this negative outlook out.

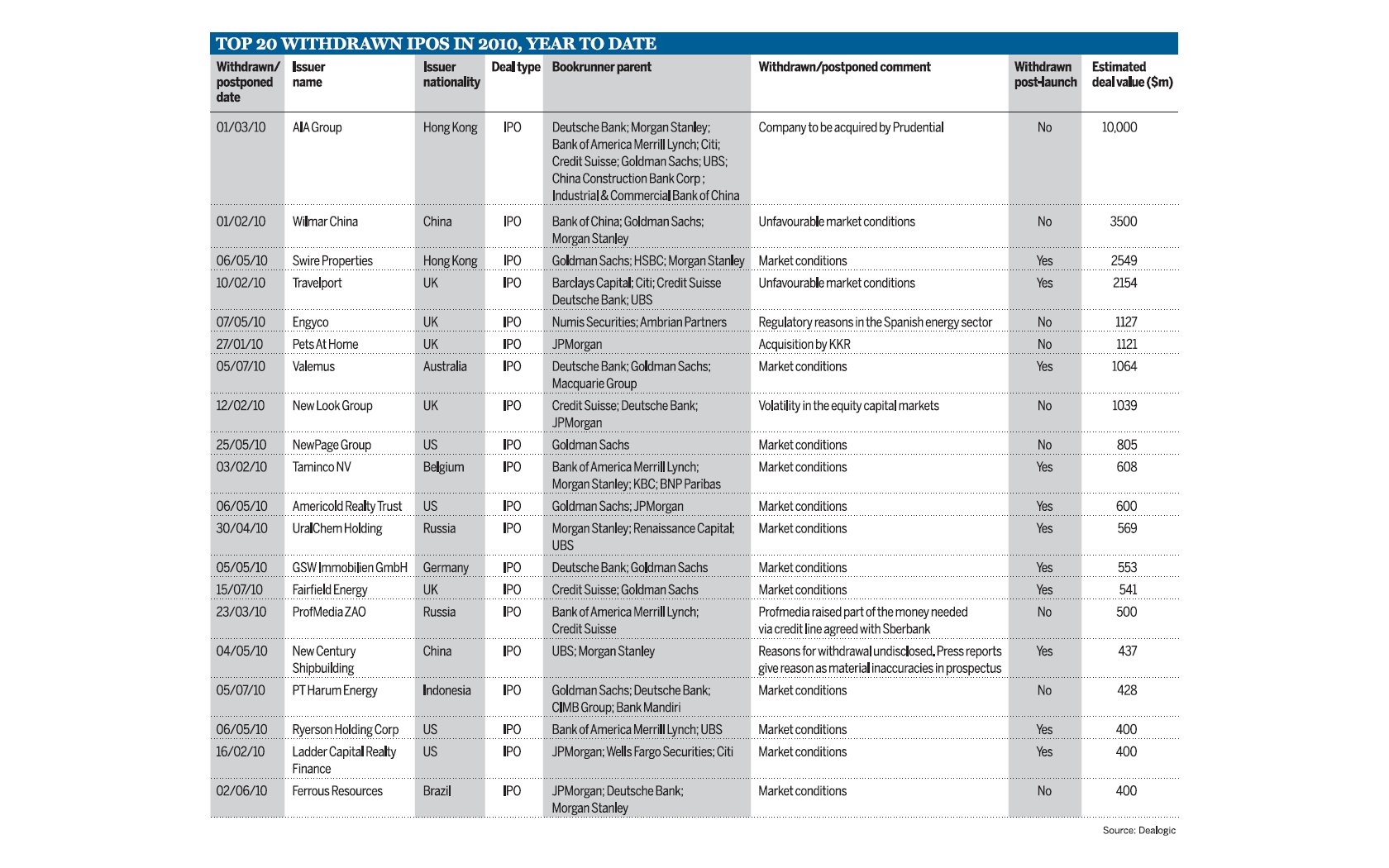

As The Banker went to press, a whopping 18 IPOs had already been pulled in 2010, and those that did make it to market failed to garner the kind of momentum needed to forge a competitive valuation. Online grocer Ocado is a case in point. The firm was forced to slash its price range from between 200p-275p down to 180p-200p. The shares priced at the very lowest end of the downgraded range - and even then sank 7% on their London Stock Exchange debut.

Neither is it just a European problem; IPOs have been flopping globally - including in the emerging markets. Russian fertiliser company Uralchem pulled its $600m flotation in April; Wilmar International, the world's biggest palm oil producer, delayed the $3.5bn listing of its China unit in February; and Brazil's Ferrous Resources cancelled a deal in June. A number of listings have also been cancelled in the US.

According to Dealogic, global ECM volume totalled $338bn over 2549 deals in the first half of 2010, the lowest first-half total since 2005 and a 4% decrease on the same period in 2009.

Such volatile conditions are likely to continue. At time of writing, equity markets across the world are volatile. Startled by a deteriorating growth outlook in August, investors sold equities and took cover in the security of bonds.

Unrealised potential

This year's market jitters fly in the face of what many had anticipated would be a bumper 2010 for the IPO market. Late last year, ECM specialists had talked excitedly of a raft of private equity exits and company spin-offs straining at the starting blocks. It wasn't to be. The pipeline of private equity deals remains just that, a pipeline, and the anticipated rush for companies to raise money by spinning off businesses has failed to materialise. Of those deals that made it to market, few have garnered any momentum.

Dan Cummings, global head of ECM at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, says that although the IPO market has been slower than expected at the start of the year, there have been recent signs of life. "It has been a slower pick-up than we had hoped but this is not surprising in light of the global market backdrop. We need a consistently stable period, but it is hard to ascertain when that will come." It has been a binary market, according to Mr Cummings. "IPOs have either been very successful or struggled to capture critical mass. It has been more about momentum and psychology than about fundamentals."

However, the fact remains that some companies are still attempting to float. Banks are going to need to equip themselves with the right strategy to achieve the best price in sometimes unfavourable conditions. On the buy-side of the equation there is reason to be optimistic. In such volatile markets there will undoubtedly be numerous pockets of value and big opportunities to invest in stable companies with good growth prospects and at rock-bottom prices.

Thierry Olive, head of ECM at BNP Paribas, believes that such quality assets count more than ever in this kind of environment. "There are no 'must-have' deals out there but there are 'must-look' deals," he says. "It is hard to capture the attention of investors, whatever the price." For Mr Olive, it is all about momentum. "If you are already one-times covered in a deal, you can communicate that to the market, add more momentum and get it even more covered," he says. "But the difficulty we have now is that if the deal is not covered, what do banks do? Particularly if it is just a few days before the proposed close of the book."

Cut-price market

The key to success in this environment is in getting the price right. Nervy investors are clearly only going to jump on sure-thing investments and even then they will demand a healthy price discount. Many have criticised the Ocado deal for failing to grasp this concept. The fact that the company was forced to reduce its price range just a day before listing killed all momentum for the deal and made it even harder to convince people to invest. As a result, the deal priced at the lowest end of the lowered range and performed poorly on the after-market. Jim Renwick, head of UK ECM and corporate broking at Barclays Capital, puts it in simple terms: "If owners price sensibly then the IPO will work. If not, it will struggle."

In the case of Ocado, another factor that might have affected best execution was the size of the firm's bank group. Goldman Sachs, UBS and JPMorgan Cazanove led the deal, with a junior syndicate of five other banks. One banker, who does not wish to be named, says that such an approach can hinder rather than help the process. "Two banks are sufficient to lead an IPO. We need a return to leadership. Running a deal by committee is a mistake," he says.

It is a view shared by others in the market and, according to another ECM banker, a symptom of the fact there are many more mouths to feed. "The problem for issuers is getting the right balance between independent advice to achieve best execution, and not having too many advisers," he says.

Despite the difficulties it encountered, however, the Ocado deal was ultimately a success. Raising any kind of money via an IPO in a market as volatile as it is today should be considered a great achievement, particularly for a company that has yet to make a profit, as is the case with Ocado.

A particular problem is timing. Given a deal can take many months to come to fruition from the initial 'pilot fishing' stage, through to investor education and finally the bookbuild, there is enormous room for error.

"So far this year we've had a debt crisis that morphed into a sovereign crisis. Risk appetite is low. Volatility is not good for IPOs," says Mr Renwick. The litany of macro-economic shocks so far in 2010 have sounded the death knell for many an IPO, and even nature has conspired to upset the apple cart. The Icelandic volcanic ash cloud that shut down the world's airways in April was both directly and indirectly the cause of several delayed IPOs. "IPO processes in Europe can be a relatively protracted business. Market volatility can change what is deemed to be the right price and the right story. Risk appetite can recede very quickly in this market," says Nick Williams, head of EMEA ECM at Credit Suisse.

Dan Cummings, global head of ECM at Bank of America Merrill Lynch

Mind games

So how can investment banks get the price right when there is so much room for investor sentiment to change, and with such alarming regularity? The first job of any ECM professional is to manage expectations. Only those companies with strong growth prospects and low leverage should even consider listing, and only then at a competitive valuation. "The deals that are getting done have ticked a specific set of criteria," says Martin Thorneycroft, head of European equity syndicate at Morgan Stanley. "They have typically had structural growth, modest leverage and good management. The market is open to good stories that are appropriately structured and priced."

Bank of America Merrill Lynch's Mr Cummings agrees. "First of all be clear about what you want to accomplish and your goals. Investors need to be reassured that the business will not need more financing in the next 24 months," he says. "It is also very important that companies have reasonable expectations about what they can achieve. The buy-side is erring to the worst-case scenario."

One way to avoid a sudden price-altering change of sentiment during the IPO bookbuild is to set the price at the very end of the process - a practice otherwise known as the de-coupled bookbuild.

By doing this, the risk of appetite changing due to market volatility is mitigated. However, it is not a strategy favoured by everyone. Setting the price at the very end of the bookbuild reduces greatly the chances of getting a competitive valuation. The de-coupled process can make it harder to generate investor appetite for the shares. "You need to give some guidance to the market, even if that does sometimes mean broadening the price range," says Mr Williams. "Without competition for the shares it is very difficult to push on price. Even if you do set the price later in the process, the reality is you still need to create the competition necessary to optimise the pricing."

Mr Olive agrees: "The de-coupled process is not a good signal. It usually means there is a discrepancy between the banks' view on the price and the seller's view."

Another method favoured by some is to widen the price range offered on the IPO from the very start. This at least gives investors a broad target to aim for and some sense of where to pitch. However, this also has its drawbacks. Mr Olive is against using a wide price range because "it is a way of hiding the truth to the issuer". "It invariably means that banks cannot convince investors," he says. "The top end [of the price range] is unreachable and even the bottom end can sometimes tend to be challenging. Everything is mind games in this market."

The right mixture

One deal that appeared to tick all the boxes and has been cited time and again by ECM professionals as the best model to follow was Jupiter Asset Management's recent IPO. The company priced its deal in a 150p-210p range, which was deemed about right. As a result, the book was 2.5 times covered. The deal priced above the lower end of the range and the shares soared 15% on their market debut. The Jupiter deal is proof that despite everything, a well-structured deal will always fly. "It is an environment where you can float good businesses at reasonable prices. You need to lead with the price, combined with a robust story ideally offering solid growth potential," says Mr Williams.

Looking ahead, there are some grounds for optimism in terms of IPO volumes, but only for the best companies. "We are in a far better position now than we were at the beginning of June. I would feel reasonably comfortable launching a transaction over the next couple of weeks," says Mr Olive. "Investors are cautiously optimistic. We are not yet at the end of the tunnel but there is no reason to be pessimistic." However, he stresses that it is too fragile an environment to support massive amounts of IPO issuance, as mid-August's equity market jitters showed. "Investors will remain selective and only look at quality assets."

Matthew Koder is global head of global capital markets at UBS. He agrees that in recent market conditions those deals that have succeeded have tended to be well executed with a good price discount, but he stresses "the buy-side only wants to pay for a sure thing". "There has had to be a compelling reason to do an IPO in this market. But as market conditions improve, IPO volume will increase."

In terms of supply, there is renewed optimism that private equity exits could once more be a source of dealflow. "Private equity has been able to de-lever more and firms are mature, bigger and with an observable past," says Mr Cummings. It is likely, however, that in a market like this it will be through partial sell-downs rather than full IPOs.

The market remains in a state of unease and selling any kind of deal, no matter how well-regarded, will be a struggle for some time. However, deals are getting priced and investors can still spot a bargain, as Jupiter's IPO showed. "The theme for this year is that the market is open, but you need to be nimble," says Mr Thorneycroft.