Wave of African bank consolidation reduces systemic risk

Bank consolidation in sub-Saharan Africa is in full swing. Large and stable banks are growing steadily as a result, while many small and inefficient banks are disappearing. Kat Van Hoof reports.

Many economies in sub-Saharan Africa have been faced with subdued economic growth rates, which makes organic growth for local institutions hard to come by. In response, there has been a wave of consolidation among banks looking to benefit from economies of scale.

More mature banking systems, such as those in Nigeria, Angola and South Africa, have seen mergers aimed at supporting long-term profitability and synergies that could help reduce funding costs. Several such deals have happened recently, with Nigerian top-tier lender Access Bank scooping up smaller rival Diamond Bank. Low valuations have plagued many regional banks, particularly in Nigeria, which simultaneously makes it harder for banks to access capital through rights issues and makes them more attractive takeover targets for well-capitalised peers.

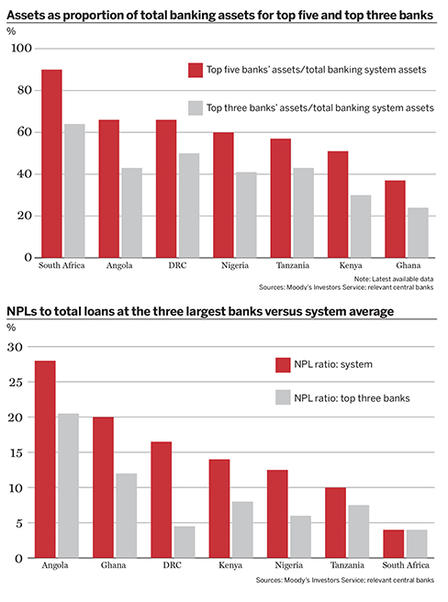

Banks in Tanzania and Kenya, which have highly fragmented banking sectors, are likely to join the fray in the next couple of years. Both countries have about 40 banks, with the top five holding only 55% and 46% of total assets, respectively. This shows that there is a large group of smaller banks that tend to have weaker balance sheets.

Many regulators across the region have adopted tougher stances on national banking systems, which is forcing weaker banks to take action. José de Lima Massano, governor at the National Bank of Angola, has said that newly introduced adjustments to the minimum capital and equity of Angola’s financial institutions, implemented at the end of 2018, could lead to more mergers and acquisitions among banks.

Bank of Ghana has also introduced higher minimum capital buffer requirements. As a consequence, the number of commercial banks fell to 23 by the end of 2018, from 34 the year before. Well-capitalised Kenyan bank KCB this year announced the acquisition of National Bank of Kenya, which has struggled with liquidity for some time, in what could be seen as a rescue operation. Moody’s expects much of the merger activity to take place in east Africa and Angola.

In order to be able to compete, smaller banks tend to service clients with weaker balance sheets, which bring in higher fees than lower risk clients. Problem loans are a materially smaller part of the loan portfolio at bigger banks, which tend to have bigger buffers in case of defaults. Increased economies of scale through tie-ups between bigger stable banks and smaller weaker institutions can help reduce the systemic risk measured by non-performing loans (NPLs).

Many regulators in sub-Saharan Africa conduct asset quality reviews in which they assess the quality of assets on the books and the financial provisions to offset these liabilities. These reviews can uncover previously unrecognised NPLs and force banks to either write down certain loans or increase provisions, which in turn affects the bank’s overall capital buffer. The regulator in Angola is conducting an asset quality review that is projected to be finished by the end of 2019, which could lead to several smaller banks falling foul of the minimum capital requirements.