Nuclear power is slowly rising in popularity as an energy provider, but project financing challenges have made these deals more difficult to get over the line. Danielle Myles looks at how these problems can be overcome.

Few topics have divided public opinion in the way that nuclear power has. Proponents are quick to tout its low greenhouse gas emissions, and the opportunities it provides to cut dependence on imported fossil fuels. To the sceptics, it is expensive, requires overly complicated technology, and involves significant safety risks. Indeed, the catastrophic accidents in Fukushima in 2011 and Chernobyl in 1986 have cast a long shadow over the sector, despite nuclear technologists’ insistence that these were 'black swan' events.

For investors, the industry also presents a dichotomy. No other power source simultaneously presents so many advantages and shortcomings, making it difficult for them to assess. “Nuclear, at least to date, is one of the very few sources of energy that isn’t intermittent and is largely available, low-carbon and economic,” says Eric Cochard, head of sustainable development at Crédit Agricole Corporate & Investment Bank (CIB). “It has hugely positive aspects, but also very significant drawbacks, from the security of the technology to waste management.”

The case for nuclear

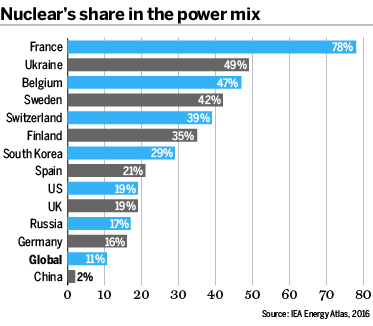

Germany and South Korea’s decisions to phase out nuclear power have made headlines in recent years, but the number of countries retreating from the sector is dwarfed by the 30-odd others speaking with international nuclear agencies about launching their first programmes. Today, there are 449 plants operating across 30 countries, with another 61 under construction.

The 2015 Paris Climate Accord, which saw 195 governments agree to limit global warming to two degrees Celsius, has made nuclear power more compelling than ever, primarily because it is the only carbon-neutral form of base-load power; it generates electricity 24/7, whereas renewables such as solar and wind power are less reliable.

But a number of factors threaten its prospects. The anti-nuclear movement has, rightly or wrongly, prompted some potential stakeholders to distance themselves from the sector to protect their corporate image. Low natural gas prices and renewables subsidies make nuclear comparatively expensive, at least in the short term. And the way construction is financed today cannot support the development of a more international industry. For nuclear power to succeed, new funding structures must be found.

An endangered status quo

Developers around the world have historically combined a handful of debt options when building new plants. Utilities use on-balance-sheet financing, relying on general purpose, unsecured corporate loans from their banks. Export credit agencies (ECAs) often help fund the import of reactors, while government schemes such as US loan guarantees and the UK Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA) programme – which guarantees a developer’s bonds to the point where they can access the sovereign debt market – are also relied upon.

This limited selection reflects the fact that the US, UK and Japan are the only countries to have privatised the sector. Equity in nuclear power around the world lies in the hands of either state-owned enterprises, or well-capitalised industrial giants that can fund new plants without eroding their credit-worthiness. But evidence suggests this is not sustainable going forward, certainly not if nuclear is going to help tackle the two degree climate cap. A number of utilities have hit tough times, including France’s Areva, which is being acquired by EDF, and the US’s Westinghouse, which has filed for bankruptcy protection. And the majority of countries contemplating their first plants – including Nigeria, Jordan, Egypt, Bangladesh, Poland and South Africa – would need more external financing than can be provided by ECAs and corporate loans.

“In a number of developing countries considering nuclear power programmes, the projects are still at the development stage and naturally, one of the biggest hurdles is finance,” says Elina Teplinsky, a nuclear power partner at law firm Pillsbury. “Electric utilities and host country governments just don’t have the funds to build these capital-intensive projects.”

Within the power sector, this predicament is unique to nuclear. Other developers rely on non-recourse project finance whereby a project company – whose only asset is the plant – borrows from commercial lenders on the basis of its future electricity sales, and in return grants security over the plant. It allows utilities to leverage construction costs, injecting the project company with just 30% equity to attract 70% in debt.

Yet in the 60 years since the first commercial nuclear power plant came online, not one has been project financed. Finland and France have experimented with different arrangements, creating the Mankala and Exceltium models, respectively, which see offtakers and investors finance construction in exchange for receiving electricity at cost price for decades, sometimes the 60-year life of the plant. But the nirvana of funding nuclear power is regarded as project finance.

Nuclear resistance

That said, those in the industry present a laundry list of reasons why project financing and nuclear power plants are not a natural fit. First, there is the sheer expense of building a nuclear plant. EDF’s latest estimate for the UK’s Hinkley Point C is £19.6bn ($25.45bn), although the industry-wide benchmark for a plant using the latest so-called Generation III reactors is in the vicinity of $10bn. If a borrower tapped every corner of the project finance market – commercial banks, project bonds and ECAs – they would still fall short of the 70% debt component typically seen in a project financing.

Second, long construction periods mean revenues – and therefore loan repayments – do not start for some time. While it takes two or three years to build a natural gas plant, the median global construction period for nuclear reactors completed in 2016 was more than six years. “There are planning and design activities that need to be financed even before construction begins. So it would be asking investors to have a great deal of patience,” says Ian Emsley, senior project manager at the World Nuclear Association. It also means utilities end up buying untested reactor designs. In most industries, developers prefer proven models, but if a nuclear reactor is ordered after the prototype has come off the production line, it quickly becomes outdated by newer technology.

Another friction is step-in rights. A project financier’s ultimate recourse against a defaulting borrower is to enforce their security by taking control of the plant and hiring a new operator to get it back on track. This arrangement works in other power sectors, where the technology is relatively comparable from plant to plant, but nuclear projects are designed for individual operators, meaning no one else is able to run it.

A headline concern is political and regulatory risk. The snap decision by South Korea’s new president to phase out nuclear power exemplifies how the sector is at the mercy of government policy. And while price guarantees, such as the UK’s 'contract for difference', are useful at locking in electricity prices, they also introduce the risk of regime change.

A more technical problem is risk allocation. Project finance principles dictate that the party best able to manage a risk should bear that risk, but this does not work in nuclear power due to the scale of liabilities involved. For example, the entity best placed to manage risks relating to a crucial widget is the manufacturer. But if the result of that widget not working is the plant breaking down, the damages would bankrupt the manufacture, prompting claimants to pursue a party with deeper pockets – namely, the banks.

Finally, operators must build a decommissioning reserve over the plant’s life, to fund its eventual dismantling. It is a sensible regulatory requirement, but means money flows out of the business before the banks would be repaid, and creates questions about who has first claim on any residual cash if the project is terminated.

Western hiatus

These problems are exacerbated by delays plaguing the latest European and US nuclear projects including France’s Flamanville 3, which is €7bn over budget and six years late, Finland’s Olkiluoto 3 (€5bn over budget and a nine-year delay) and the US’s Vogtle 3 and 4 (€3bn over budget and a three-year delay).

These rank highly on bankers’ lists of reasons to be wary of project financing nuclear power, but the problems are not emblematic of the sector. Projects operated by Chinese and South Korean entities, for instance, have largely run to schedule. The fact that these countries have well-established construction programmes is no coincidence. “They are like a well-oiled machine,” says Mr Emsley. “Supply chains are in place, regulators are used to inspecting reactors and processes, and very often they are built on the sites of existing plants. So it all goes very smoothly.”

Europe and the US, meanwhile, are emerging from a long construction hiatus. As William Magwood IV, director-general of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Nuclear Energy Agency notes: “In many countries, we have this unfortunate habit of not building plants for 15 or 20 years, and then when we try to build new plants, we discover we don’t have the supply chain, managers or expertise needed and therefore run into problems.” Recent projects in the US, France and Finland, he says, are good examples of what can go wrong without the right project infrastructure in place.

Overcoming the hurdles

These challenges are not insurmountable. Support industries and skillsets will be re-built over time (in the interim, bankers tell stories of welders being brought back from retirement to build new plants) and the technical barriers to project finance can be worked around. All things considered, industry participants, including Mr Magwood, concur that the sector can be made bankable, and they have outlined the conditions for this to occur.

Lenders would demand more than the usual 30% equity layer in a project company, which reduces the amount of debt that must be raised. But borrowers would need to be strategic in finding this debt. “If you spread your supply chain across the world you can maximise the availability of ECA financing,” says Vincent Zabielski, a senior member of the nuclear power team at Pillsbury. “So, for example, buy your reactor cooling pumps from Westinghouse to get the Export-Import Bank of the United States involved, and source other major components from Korea and Japan to encourage the Export-Import Bank of Korea and the Japan Bank for International Cooperation to lend. If you had a few big anchor lenders, commercial banks would probably be more inclined to get involved.”

The smallest possibility of banks having to shoulder any nuclear-specific liabilities – relating to an accident, for instance, or radiation leak – would make the deal a non-starter. Ms Teplinsky believes there are different models via which debt providers – and minority equity investors – can take project risks without nuclear risks. “Liability is channelled to the operator of the plant, so it’s best to structure these deals so that lenders or investors aren’t asked to back or invest into the entity holding the nuclear liability risk, but an entity shielded from that risk,” she says.

However, as demonstrated by the widget example, a normal indemnity clause from a utility or operator is not enough to protect private lenders. “The key things are how to get comfortable with any potential nuclear liability, and the indemnification you have on that,” says Carol Gould, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group’s head of power and renewables. “You need a very big balance sheet to sit behind that, and your average corporate is not going to be that party. It means banks would likely demand a sovereign guarantee to act as an ultimate backstop regarding nuclear liability.

They would also require the shareholders to take construction risk. Ms Gould adds another requirement: “You need change-of-law covered off. You don’t want to find yourself with a stranded asset if a country decides it no longer wants nuclear in its power mix.”

Banks’ nuclear power policies reveal other priorities. Crédit Agricole CIB requires careful assessment of the technology, the operator’s capabilities, and whether the host regulator has teeth. “It must have an agency that is independent from the operators, and which has some power to stop a project,” says Mr Cochard. “Not all countries have this kind of authority, but for us, it’s absolutely key.” It means, ironically, examples of regulators halting projects – including the French authority stopping Flamanville temporarily due to design concerns – are reassuring to lenders.

This leaves long construction periods as the main issue. However the next generation of reactors currently being built – known as small modular reactors (SMR) – could present a solution. They are cheaper and quicker to assemble than Generation III reactors, and small enough to be constructed in a factory and transported to the plant by rail. Debt repayments could begin sooner, and as building any product in a controlled environment such as a factory tends to improve efficiencies, there are less likely to be delays. Ms Teplinsky, among others, believes SMR technologies could present an opportunity to use project finance models.

Barakah’s baby steps

The most encouraging sign yet that the sector can be project financed is Abu Dhabi’s Barakah project. The United Arab Emirates' first nuclear power station will come online in 2018, broadly on schedule, after securing $24bn in debt financing from ECAs, the Abu Dhabi government and a handful of commercial banks.

Although the banks provided a very small slice of the debt, those involved in the deal affirm it has been structured as a true project financing vehicle, but with added credit support and guarantees to cover key risks. This includes completion support provided by the two developers – Kepco and the Emirates Nuclear Energy Corporation (which is backstopped by the Abu Dhabi government). “It’s a typical project financing [deal] in terms of covenant protection – i.e. the banks are focused on the plant’s ability to generate revenue – and the loan agreement and underlying contracts are structured as if it’s a limited recourse loan,” says Calvin Walker, a partner at Baker McKenzie, which advised Kepco.

Others involved in the deal confirm that the borrower entity is not subject to nuclear-related risks, and that the step-in mechanism allows lenders to improve commercial disciplines and control operations if the project runs into problems, but all the while maintain their distance from the actual nuclear plant.

A win-win situation

Barakah proves that if a host government is willing to provide a benign environment, it is possible to project finance nuclear power. It is hoped that the project’s success, and the foreign investment it has generated, may encourage other governments to follow suit.

For the industry it would be a clear win. Allowing developers to leverage construction costs would lower the barrier to entry, improve competition and increase efficiencies. Limiting them to balance sheet funding and government finance is proving too big a burden on private sector sponsors, in particular. “The utilities no longer have billions of pounds to invest entirely on their own,” says Ms Gould. ”Now it’s a case of how they raise the financing, and the only way to do this without affecting their balance sheet is to look at debt financing via an off-balance-sheet-type structure.”

There is significant upside for banks too, including a high return. The best indicator of this is the Hinkley Point C state-aid decision. The European Commission approved the UK government’s assistance via the IPA scheme on the grounds that the developers did not receive a pricing benefit on their debt. After some hefty analysis, it was concluded that the coupon on the BB+/Ba1 bonds, combined with the 295 basis point guarantee fee the developers paid the UK government, reflected the market rate of the debt. These figures are particularly impressive in a low interest rate environment. In addition, nuclear power’s coverage ratios are significantly higher than at gas and renewable plants, meaning they are less likely to default on repayments. This is because costs are relatively fixed once a nuclear plant is online, making it among the world’s most reliable power assets.

Ten new plants came online in 2016 – the highest number since the 1980s – which indicates the industry is at the beginning of a new construction cycle. If this reassures lenders that plants will soon be delivered on time and on budget, it could lay the groundwork for a new era of project financed nuclear plants. As Mr Zabielski muses: “There’s nothing really so different about nuclear projects that can’t be overcome. It’s just that we’ve forgotten how to build them.”