A brave new world for commodities hedging

Oil prices are recovering, but for producers, consumers and even investors, some of their most difficult decisions are just beginning. Danielle Myles reports.

After nearly two years of trials and tribulations, there is a sense of cautious optimism in the oil industry. Since prices dipped below $30 per barrel in February, both the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Brent benchmarks are hovering around the $50 mark and, despite the false dawn of early 2015, the broad consensus is that prices are on a chequered path to recovery.

The rollercoaster ride experienced by the full spectrum of market participants – producers, consumers and investors – has, in some ways, played out on banks’ commodity desks. “Mid-2014 seems like a decade ago,” says Jonathan Whitehead, global head of commodities markets at Société Générale Corporate & Investment Banking (SG CIB). “Back then, corporate hedgers weren’t scared and investors weren’t interested. No one really believed that there was going to be a significant amount of upside from the price levels, and there were more exciting things happening in other asset classes.”

Since than, client requests have come in fits and starts, depending on their view of how prices would move next. After the first quarter of 2015 saw an uptick in consumer hedging on the mistaken belief prices had hit rock bottom, corporates were paralysed by the fear of locking in prices to their detriment. Today, with most believing prices have bottomed out but that volatility is here to stay, longer term risk management and investing tactics are being reassessed. It has led to a pivotal moment for commodities hedging, defined by new strategies and new players.

Producers: a bifurcated market

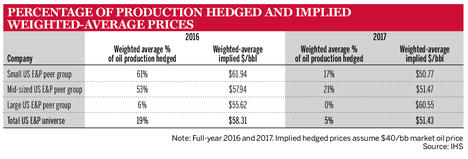

Data from energy consultants Wood Mackenzie and IHS reveals that hedging by North American exploration and production firms rebounded strongly in the first quarter of 2016, despite futures prices being lower than in the preceding quarter. It suggests they were wary of catching a falling knife by hedging close to the bottom, but also shows how risk adverse they remain, even with prices rallying.

More from this report

“For 2016, a lot of companies have added hedging in the $40 to $45 range – which is below current WTI prices – so they have seen the value of making sure they are protected from the downside, even if it has come at a cost to the upside,” says Paul O’Donnell, principal analyst at IHS Energy. He attributes this partly to the lower production outlook, but also the fact that smaller, leveraged producers have an asymmetric risk profile. Put differently, the repercussions of being unhedged and spot prices dropping $15 are much greater than of being hedged and missing out on a $15 price rise.

The spike in hedging is partly because shale producers’ three-year hedging programmes – as required by their revolving credit providers – are starting to roll off, meaning the attractive prices they secured for 2015 have not stretched into this year. But whether small and mid-cap producers, which have been hit hardest by the price collapse, have taken part in this flurry depends on their break-even point – which for many hovers around the prices they can secure today for 2017 and 2018.

“The ones that are profitable at $45, and there are plenty in US shale oil that are, after having suffered a near-death experience two or three months ago, are actually quite active at the moment. They are locking in prices whereby the returns they are making may not be fantastic, but at least they can guarantee their survival,” says Mr Whitehead. But for those that are not profitable, rather than locking in and securing their fate, they have little choice but to gamble on prices sharply rising.

Long-short strategies find fertile ground

The price slump combined with severe volatility – the Crude Oil Volatility Index hit a post-crisis high at the start of 2016 – has jolted to life pension funds, asset managers and speculators alike. For the first two, it is yet another impetus to look beyond their historic, broad-based index investments and towards volatility products and those offering a risk premium. “As commodities started coming off, and therefore long-only strategies started underperforming significantly, that really accelerated the move to people searching for a good, long-short or market neutral strategy,” says Jonathan Whitehead, global head of commodities markets at Société Générale Corporate & Investment Banking (SG CIB).

Managers have pushed into this space for five or so years now, but recent events have prompted a new level of sophistication. But in itself, going long-short is not bulletproof. A valid concern raised by some investors is that with the current price curve being in contango, executing the long aspect of the strategy means they must pay a premium each time they roll into the next month’s future, which erodes the value of their investment over time.

SG CIB has responded by suggesting an alternative strategy based on equities that are highly correlated to commodities. “It is actually a bit of a market inefficiency in that equity values rarely tend to reflect the shape of the forward curve. So if you can find a basket of equities that almost replicates that pure, underlying commodities investment, you can actually negate that contango effect,” says Mr Whitehead.

While speculators’ fine-tuned strategies have had less scope to change, the players themselves have. “Five years ago, the space was dominated by commodity-specific hedge funds, where that was pretty much all they did,” says Mr Whitehead. When commodity prices flattened many of them disappeared, and while trading has spiked in line with volatility, it is thanks to a new generation of players. “The increase we see today seems to be from multi-asset hedge funds – either macro hedge funds or equity hedge funds that see interesting things happening in commodities and so are starting to put money to work in that sector,” adds Mr Whitehead.

Oil hedging

While shale’s hedging decisions are a matter of survival or bankruptcy, a very different dynamic is playing out among the oil majors. As their downstream and midstream segments create a natural hedge for their production they do not, by and large, embrace long-term commodity derivatives. But after a period of stress so severe that even Shell, Chevron and Total have had their credit ratings slashed, the strategy becomes more compelling.

“As prices recover to more healthy levels, it will be interesting to see if some of the larger independent producers and even integrated oil companies contemplate putting on some hedging programmes. I wouldn’t necessarily bet against it,” says José Cogolludo, Citi’s global head of commodities sales.

Andy McConn, a senior analyst at Wood Mackenzie, has observed some already re-examining their stance. “One example is Apache. Traditionally it never hedged, but in the past few quarterly calls it has said if prices get to a certain level it could introduce a hedging policy,” he says.

Opportunistic consumers

The hedgers to suffer most from the oil rout are airlines which, given fuel is one of their biggest expenses, dominate the consumer client base. While American Airlines’ decision two years ago to abandon its programme has paid off, others have been stung by tumbling prices. Delta’s risk management policy created a $1.2bn mark-to-market adjustment that same year, while in 2015 Cathay Pacific suffered $1.09bn of fuel hedging losses.

Over the course of those years most pulled back from the typical strategy of being fully hedged for the front year, two-thirds for the second and one-third for the third. But the first quarter of 2016 has seen them return strongly, with some buying protection out to 2019. Starting last year some airlines sought to restructure their hedges by rolling some of the higher prices locked in for 2015 into future years. By spreading their mark-to-market liability over a longer period, they are now having to sacrifice buying at the current low prices, but they can smooth their fuel costs over time.

The next biggest losers among consumers have been commodity companies, which often buy protection for their large diesel costs. “Anyone who has hedged their oil consumption on the mining side is actually getting a bit of a double whammy at the moment,” says Mr Whitehead. “Not only are they locked in at higher prices for oil, but they are also suffering in terms of their revenue.”

They, along with other industrial consumers and shipping companies, now see hedging as a great opportunity and are increasingly approaching the big derivative houses to set up risk management policies. “If you are a consumer who hasn’t hedged so much in the past but who has been exposed to $100 [per barrel] oil, locking in prices at $52 dollars for two years doesn’t necessarily seem like a bad idea, particularly as the outlook for oil prices has become much more constructive recently,” says Mr Cogolludo.

An expanding toolbox

Accounting and auditing requirements mean corporates historically prefer vanilla structures – particularly swaps as this lets them lock in a straight price. But while simple instruments still form the building blocks of their strategy, since late 2015 many have shown greater willingness to embrace creative ways to cover their often complex exposures.

Of the oil exploration and production companies tracked by IHS Energy, 57% of their 2016 hedging consists of swaps, 22% two-way collars and 20% three-way collars. It contrasts to gas, which has suffered depressed prices for much longer, where the corresponding figures are 90%, 4% and 6%. Data tracked by Mr McConn of Wood Mackenzie suggests that among the bigger oil exploration and production firms there is an increase in the use of three-way collars and enhanced swaps. “Companies have demonstrated that they are prepared to trade away more price upside in return for better terms on the downside risk,” he says.

This partly reflects producers’ defensiveness as prices slowly rise, but also clients’ increasing sophistication and desire to incorporate their own views into their risk management policies. It is perhaps most apparent in the growth in popularity of costless collars. By buying a put option that is funded by selling a call option, they create a price band that allows them to benefit from price fluctuations.

“The call option is sufficiently high such that, if prices are at those levels, you will be extremely healthy so you can afford to pay out the value of that call option,” says Mr Whitehead. “Both options are dependent not only on the absolute price levels but also the volatility. So you can do more interesting things when volatility is higher as the products that you are buying and selling have a higher value. They were popular before mid-2014 but those products are more attractive now.”

Assessing options

Option strategies are also in favour among consumers as they create ways to access lower prices if the current rally reverses. And if the oil majors do implement hedging strategies, Mr Cogolludo suspects it will be through put options or put spreads – partly because, unlike a smaller producer, they must consider stakeholders with potentially varying risk appetites.

While the desire for hedge accounting has fuelled a relatively vanilla commodity derivatives market, as a priority it has taken a back seat for some producers – as evidenced by the growth in three-way collars and other ineligible structures.

“What we see is that when you have a stressed environment, more corporate clients are willing to consider structures such as extendible swaps where they are monetising optionality, even though those structures require the client to mark-to-market the value of those positions through their income statement," says Mr Cogolludo. The extendible feature does not get hedge accounting, but the producer does receive a premium, which may allow them to cover their production costs or fall within budget.

Lessons and legacies

As risk management policies are reworked and hedges put back on, market participants will focus on finding strategies that work best during an upswing. In the meantime, they can point to some shifts that will transcend market cycles, including more hedging by sovereigns. While Mexico is the classic example of a government that has hedged and got it right (in 2015 its strategy generated a multi-billion-dollar payout) others have experimented in this space. In 2013 Morocco bought call options while Jamaica followed suit last year.

But Mr Cogolludo expects the real growth to come from those hit by the rout. “Because of the challenging market conditions of the past 18 months, it is fair to say that more exporting countries are now focused on risk management in the context of fiscal planning. When you go through a big move from $100 down to $30 and back up again, the level of awareness of price risk exposure certainly increases. Consequently, we would expect to see incremental sovereign hedging activity in the future,” he says.

Another change could see banks that finance small to mid-cap exploration and production companies – typically through reserve-based revolving credit facilities – toughening up their hedging requirements. “They already do it to some degree, but producers naturally have a certain amount of flexibility. But I definitely think banks have become more thoughtful and more disciplined in requiring more hedging to protect their loan portfolios,” says Mr Cogolludo.

Taking it a step further, unsecured noteholders – which have been wiped out in the oil sector bankruptcies over the past 18 months – could demand similar arrangements. “I wouldn’t even be surprised if we eventually see high-yield bonds in the natural resources space that incorporate risk management programmes that protect bond holders from sustained low commodity prices. That’s more a possibility today than ever before,” adds Mr Cogolludo.

Whether these changes materialise or not, there is broad agreement that corporates will maintain a steadier level of hedging going forward. “Even if we went back up to the prices where people are comfortable again, you will see still elevated levels of risk management and hedging, as today’s difficulties will be in very recent memory,” says Mr Whitehead.