Nathanael Benzaken, head of development for Lyxor Asset Management's managed account platform in Paris

As investor demand and regulatory pressure drive a greater level of risk control and transparency among hedge fund and derivative offerings to private investors, managed accounts and UCITS 3 wrappers are providing a safer route to alternatives exposures. Writer Hugo Cox

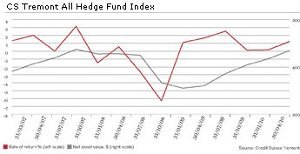

Private investor demand for managed account investing is growing, and at the heart of this growth is the proposition that this method provides access to hedge fund returns without the risks associated with hedge fund managers.

Hedge funds typically begin life as small boutique companies and are often not structured to manage the operational risks associated with their growth. By segregating client assets in separate accounts held by an independent party (the managed account provider), managed accounts ensure that certain requirements regarding the custody, valuation, trading strategy and availability of those assets are met. The managed account thus provides an institutional framework in which to manage this hedge fund boutique risk.

Not all managed accounts provide protection from all types of risk: many of the funds stolen by Bernard Madoff fraud scandal were removed from managed accounts. But the more demanding managed accounts retain custody of the assets with the managed account provider, to whom the fund manager will purely provide execution instructions.

The accuracy of performance data, notably ensuring that the net asset value (NAV) is calculated by an independent party, has climbed to the top of the agenda for investors in the wake of the Madoff case, too. In December 2008, Swiss private bank Union Bancaire Privée, then the largest global allocator to hedge funds on behalf of its private clients, became the first major investor to withdraw all assets from funds not using independent fund administrators to calculate fund NAVs. Most private wealth managers have followed this lead, with managed accounts a popular route to enforce independent valuation.

A further risk concerns the broad operational risk associated with the boutique environment from which many hedge fund managers have grown. "This concerns the robustness of operations entailed by the availability of staff to reconcile, trade and settle trades to the right prime broker, as well as the presence or absence of carefully negotiated prime brokerage agreements that shield investor assets from counterparty risk," says Nathanael Benzaken, head of development for Lyxor Asset Management's managed account platform in Paris.

Fingers burnt

Both investors and their fund providers have had their fingers burnt lately on the operational front. Custodians faced considerable uncertainty following the Madoff fraud in some countries, where local legal discrepancies emerged over the obligations of depositaries to return assets to investors.

Managed accounts also ensure that a manager sticks to the trading strategy agreed with the investor. Problems created by 'style drift' typically follow a fund overconcentrating the portfolio in a sector or instrument that is proving especially profitable, at a cost to the fund's wider risk management. The failure of Amaranth Advisors based in Connecticut, provides perhaps the best example of the dangers of this. At the time of the collapse of the $9bn fund in September 2006, roughly two-thirds of the portfolio was invested in natural gas futures, with a leverage ratio approaching eight times the total asset value.

Ensuring against excessive portfolio concentration is especially important when it comes to hedge funds, says Mr Benzaken, because of their vulnerability in times of market dislocation. "The relative-value approach that characterises the classic arbitrage trading strategies suffers particularly at times of market dislocation, where normal correlations break down and statistical measures depart from the mean," he says.

Managed account providers may have to bring specialised knowledge to bear to provide the manager with the freedom required to generate returns while being able to spot departures from the agreed trading strategy. Unless the nuances of the instruments employed, the trade durations and leverage profiles of positions are all understood, simple risk-management models may fail to detect over concentration over the short term, or may trigger too early and so shut down potentially lucrative trades.

Liquid assets

The liquidity crunch of 2008/09 is indelibly marked on the memories of many private investors and is a third area in which managed accounts can make a difference. Funds of funds, in particular, struggled to meet widespread investor redemptions. They found themselves turned away by the funds they were invested in, as managers who would not or could not meet redemption requests, because of the illiquidity in underlying assets, imposed gates or suspended redemptions entirely. Because strict managed accounts require custody of the assets with the managed account provider, the investor is always able to force a sale in such a case. In less invasive structures, managed account providers will ensure that managers with liquidity constraints can be excluded from the portfolio.

But managed accounts are not without their problems. Uppermost among these is the considerable administrative demand they place on hedge fund mangers. This can mean that many of the best managers will refuse to accept investor assets segregated in this way. Nick Sketch, senior investment director at UK private client stockbroker Rensburg Sheppards Investment Management, cautions that, while the structures have certainly made life much easier for investors, in particular increasing the transparency provided to hedge funds by their component funds, the operational requirements can be onerous.

"Managers must be able to answer some tough questions. Are they prepared to run a separate account? Can they ensure every investment can be divided pro rata between accounts? Can they guarantee all investors have been treated fairly around redemptions? Many are not prepared to do this," he says.

Have passport, will travel

The Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) is a set of EU directives, designed for fund distribution to retail investors, that allow funds to sell throughout the EU if they follow a certain set of rules controlling, among other things, trading strategy, the concentration of assets, redemptions and leverage levels.

The appeal of the European passport provided by the UCITS 3 wrapper is increased given the uncertainties created for fund distributors by the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD) currently making its way through Brussels, and likely to be passed by the autumn. This will certainly curtail the freedom with which hedge funds can be marketed to sophisticated private investors in the EU, and a recent survey demonstrates that providers are flocking to the UCITS structure to avoid its strictures. Sixty per cent of alternative investment funds surveyed by the EDHEC Business School in France, managing a collected €7000bn, agreed that the AIFMD leads to uncertainty about the distribution of funds; 65% reported that they plan to restructure their funds as UCITS.

UCITS 3 wrappers offer investors many of the benefits of managed accounts without the fees imposed by managed account providers. UCITS has become a recognisable standard now attractive well beyond the EU; Asian investors have become significant buyers of the funds.

Ben Gutteridge, senior analyst for structured products and alternative investments at wealth manager Brewin Dolphin, notes the appeals of UCITS. First, liquidity is high, with a minimum of fortnightly dealing imposed, and mass withdrawals provided for by rules that require funds to be able to redeem 20% of their units every two weeks, which limits allocations to illiquid assets. Diversification is ensured by requirements that funds invest no more than 5% of assets in transferable securities or money-market instruments issued by the same body.

Second, UCITS avoid the problem of listed hedge fund vehicles, the liquid alternative, where the price of the fund typically trades at a considerable discount to the NAV of the underlying assets, reflecting its lower level of liquidity. And, as with managed accounts, the declared constraints imposed by UCITS structures add a layer of transparency and remove the operational risk associated with smaller hedge fund managers. A final benefit in the UK is around tax treatment. Profits from funds of hedge funds are typically taxed as income, the current top rate being 50%. Gains in UCITS funds by contrast, are treated as capital gains, currently at 18% - though likely to rise in the June 2010 budget.

A key difference

However, UCITS requirements differ from those of managed accounts in one significant way. On a managed account platform, the investor can customise the rules governing how the fund is managed, balancing their own risk appetite and transparency needs with the manager's need for freedom to generate alpha. In contrast, UCITS requirements are standardised. The problem is that, because UCITS limits what managers can do with their strategies, returns will be less impressive. Most respondents in the EDHEC survey fear that structuring hedge fund strategies such as UCITS will distort strategies and diminish returns.

In particular, the liquidity and diversification constraints imposed by UCITS 3 place 'off limits' a lot of potentially lucrative trading opportunities in the derivatives, fixed income and equity space. "A lot of hedge funds have made strong returns lately out of levered exposure to small caps, convertible bonds and distressed debt; strategies that are either too illiquid or too concentrated to fall under UCITS," says Mr Gutteridge.

Liquidity restrictions were of particular concern among those surveyed by EDHEC: 69% of respondents reported that "the liquidity premium of hedge fund strategies will disappear and that performance will fall" when hedge fund strategies are structured as UCITS. This is a particular problem when you consider that many private investors are happy with reduced liquidity in part of their portfolios. "A family office with an investment horizon of two or three years may be very happy with managers investing in illiquid products," says Chris Day of Merchant Capital, a London-based firm that structures UCITS wrappers for hedge fund managers and distributors.

Ben Gutteridge, senior analyst for structured products and alternative investments at wealth manager Brewin Dolphin

Limited strategies

For those seeking access to illiquid asset classes while maintaining a level of transparency (and liquidity) in the investment vehicle itself, the listed investment trust is likely to be the favoured route. Here the discount that typically emerges between the underlying assets and the listed vehicle is a risk that the investor must get comfortable with, and that should form part of due-diligence processes.

Another challenge concerning UCITS 3 is that as the range of fund strategies is still relatively limited, with the majority of funds concentrating on long-biased long/short strategies, and with holdings mainly consisting of large cap liquid equities. Successful providers such as Blackrock, Gartmore and Cazenove have their roots not in alternative asset management but in long-only funds. They bring established relationships with private banks, and established brands among high-net-worth investors. They are also pricing aggressively, with fees typically about 1.5% for management and 10% of performance gains, rather than the 2%-and-20% structure common in the hedge funds world.

The dominance of long-bias strategies is disappointing for two reasons. First, these funds show the strongest correlation with equity markets, limiting the diversification benefits that bring investors to hedge funds in the first place. Second, the provision for derivatives exposure in UCITS 3 funds means that low-correlation, derivative-rich strategies such as commodity trading advisors, commodity pool operators and global macro are well suited to the strategy. Forty per cent of respondents to the EDHEC survey noted that these strategies ought to be most likely to take advantage of the UCITS structuring. But so far, this has not happened.

Those specialist hedge fund providers that have proved themselves in this space, including Brevan Howard, Marshall Wace, BlueCrest Capital and GLG Partners, are offering an increasing number of market-neutral strategies. But their overall presence in the UCITS industry remains small, and they seem to be finding it more difficult than traditional asset managers to raise money for UCITS hedge funds.

Specialist fund managers who are tempted to squeeze their strategies into UCITS wrappers to chase investor assets should beware. "Some of the best exponents of traditional strategies are not doing well when adapting these strategies to UCITS wrappers," says Mr Sketch. Brevan Howard, he explains, provides one such example. The Brevan Howard macro strategy that feeds the unit trust product, for instance, showed about 7% growth last year. The UCITs version was up just 2%.

Alternative approaches

The Brevan Howard example illustrates the fact that hedge funds are finely balanced strategies: the way that different asset classes interact means that withdrawing a certain element can have a disproportionate effect on performance. Mr Sketch says: "At one level it's like having a horse with four legs that runs at 40 miles per hour, and saying that when you back-test that horse with three legs it can run at 30 miles per hour."

Managers such as London-based Man Investments have attempted to circumvent this risk by writing total return swaps - in its case with Deutsche Bank - to make up the difference of return between the core strategy and the UCITS vehicle. The problem here is that the route may fall foul of future regulations - this is, after all, securing investment returns inside the UCITS structure with instruments that the regulations intended to keep outside. In addition, it introduces a credit risk from the counterparty writing the swap.

The key with investors' use of UCITS funds, concludes Mr Day, is a clear understanding of its purpose. "If you're thinking about replicating futures exposure, for example, you must ask what elements of the exposure you are trying to replicate. If it's leverage, then the structure cannot give you that. If it's a hedging need, then what UCITS can provide you with is a consistent understandable framework within which to operate such a strategy," he says.